SCOTUS, on a 7-2 vote, strongly rejects a challenge to the CFPB

A rebuke to the Fifth Circuit from Thomas and a win for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. A concurrence from Kagan, meanwhile, challenges originalism. And: A Law Dork update!

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau emerged unscathed at the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday from a right-wing effort to knock it out.

What’s more, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, soundly and strongly rejected the challenge to the CFPB’s funding structure — and the decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit that bought the argument. Only Justices Sam Alito and Neil Gorsuch dissented.

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress set up the CFPB to protect consumers in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Its funding, set forth in the law, comes from the earnings of the Federal Reserve System, subject to a statutory cap. The CFBP’s director determines how much of that amount is needed in any year to carry out the CFBP’s “duties and responsibilities.”

Thomas, writing for himself and the six other justices, held that the CFPB’s funding structure adheres to the constitutional limits set by the Constitution’s Appropriations Clause. At the end of the day, Thomas’s opinion is rather simple:

In support of the challenge — brought by opponents of the CFPB’s payday lending rule — Alito wrote a ranting 25-page dissent, for himself and Gorsuch. At one point, Alito literally wrote that the combination of what he views as layers of insulation from accountability for the CFPB to Congress “is deadly.” There was no further justification for his use of such extreme language about bureaucratic policy decisions.

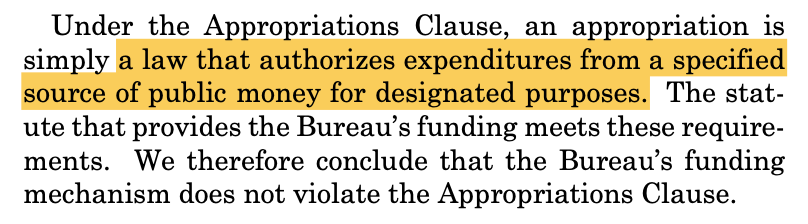

In his dissent, Alito accused Thomas and the court of turning the Appropriations Clause into a “minor vestige” with its interpretation. That interpretation, however, is textbook Thomas. As Thomas wrote for the court:

Alito, in response, claimed, “The Framers would be shocked, even horrified, by this scheme.” In truth, he simply didn’t like Thomas’s conclusions about that text and history, which they recount — in painstaking (painful?) detail.

Thomas pushed back, though, as well, writing that Alito’s dissent “never offers a competing understanding of what the word ‘Appropriations’ means” and “does not meaningfully grapple” with the history as detailed in Thomas’s opinion for the court.

Putting history aside, I would just add that it’s remarkable to read Alito’s dissent, see him note that there is a limited amount of money set out for the CFPB, and then see him continue to argue that it’s not an appropriation.

As noted, though, Alito had only Gorsuch trudging alongside him on Thursday.

Thomas rejected that — and the Fifth Circuit’s ruling — concluding, “The statute that authorizes the Bureau to draw money from the combined earnings of the Federal Reserve System to carry out its duties satisfies the Appropriations Clause.”

[Update, 1:00 p.m. May 17: There has already been significant fallout — and a flurry of filings — in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s challenge to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s credit card late fee rule due to Thursday’s decision. More here in a note.]

The concurrences

The ruling itself was not the only important action happening in the decision in CFPB v. Community Financial Services Association of America.

Justice Elena Kagan wrote an opinion concurring with everything that Thomas wrote, but adding another important factor to her consideration of the challenge. Even more importantly, she was joined in doing so by Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.

In addition to agreeing with Thomas that, as she put it, “[t]he CFPB’s funding scheme, if transplanted back to the late-18th century, would have fit right in,” Kagan added, “I write separately to note that the same would have been true at any other time in our Nation’s history.”

This segued to a fourth area supporting the constitutionality of the funding structure beyond the text, history, and congressional practice “immediately following enactment” discussed by Thomas. “[S]o too does a continuing tradition,” Kagan wrote, detailing that continuing tradition over three pages.

Then — again, joined by Sotomayor, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — Kagan concluded:

Whether or not the CFPB’s mechanism has an exact replica, its essentials are nothing new. And it was devised more than two centuries into an unbroken congressional practice, beginning at the beginning, of innovation and adaptation in appropriating funds. The way our Government has actually worked, over our entire experience, thus provides another reason to uphold Congress’s decision about how to fund the CFPB.

This is something different, and it matters. Kagan challenged originalism, and she had Kavanaugh and Barrett, along with Sotomayor, join her.

Lest there be any doubt about the significance of this, one only need look over at Alito’s dissent:

For Alito — and Thomas — it would be an extremely concerning development if Kavanaugh and Barrett’s constitutional understanding and constrictions become untethered from a history-only mindset. This is a development to watch — a potential crack in the restraints of originalism.

Finally, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote her own concurrence, highlighting a different point — one she made at oral arguments back in the fall and that I covered here at the time at Law Dork. She thought this was a much simpler case because, in her view, the courts shouldn’t have been delving into any of the ins and outs that the other three opinions examined.

“When the Constitution’s text does not provide a limit to a coordinate branch’s power, we should not lightly assume that Article III implicitly directs the Judiciary to find one,” she wrote.

Here, under “the plain meaning of the text of the Appropriations Clause,” the statute setting forth the CFPB’s funding structure “easily meets” the textual requirements. “In my view, nothing more is needed to decide this case,” she wrote. This approach, she continued, is important because the political branches must be allowed “to address new challenges by enacting new laws and policies—without undue interference by courts.”

There is a big-picture justification to this argument, she wrote — one that draws a sharp contrast with Alito’s dissent and its argument that the judicial branch should have acted here to stop Congress from taking action that he said amounted to it giving away its authority.

“[T]he principle of separation of powers manifested in the Constitution’s text applies with just as much force to the Judiciary as it does to Congress and the Executive,” she wrote. And, in contrast to Alito’s repeated concerns about the “insulation” the CFPB was given from Congress (by Congress), Jackson responded with reasons that Congress could have had for making those decisions — reasons that she wrote are “illustrate[d]” by the case.

“Drawing on its extensive experience in financial regulation, Congress designed the funding scheme to protect the Bureau from the risk that powerful regulated entities might capture the annual appropriations process,” she wrote, adding, “Respondents, two associations of payday lenders, represent exactly the type of entity the Bureau’s progenitors sought to regulate and whose influence Congress may have feared.”

And, a Law Dork update

On Wednesday, I published my 366th post at Law Dork. In honor of it being a leap year, I decided that’s when I would count a year of posts. I did so in a little less than 2 years of Law Dork — that comes on June 21 — so I’ve been publishing a little more than every other day over these first two years (with an increasing frequency, so it’s more like four or five a week these weeks).

In that time, I’ve brought you the big Supreme Court news, with my unique insights, but also some of the most incisive reporting and analysis on legal developments involving LGBTQ people, the criminal legal system, democracy, the post-Roe landscape, immigration, and more. Throughout that time, I’ve shared hundreds if not thousands of documents with you, conducted many interviews and Q&As, added Law Dork Video, and — for paid subscribers — started The Law Dork Nine.

With more than 30,000 total subscribers, I’m also very proud to announce that I hit my initial two-year goal of 2,000 paid subscribers on Monday.

I couldn’t be more grateful for the opportunity that you all are giving me to do the journalism that I think needs to be done in the way that I think it needs to be done in this era in which we live.

As we enter an extremely busy period for the law — and our lives — that won’t likely slow down completely for some time, thank you, sincerely and completely, for the trust and time you all give me.

Also — and, importantly as we head into June (and renewals) — I am also thrilled to announce that the subscription level and growth is such that I am able to commit to another year of Law Dork.

Please do make sure that you are able to renew your subscription — especially if you have an annual subscription — by checking that your credit card info on file is up to date.

And, if you are a free subscriber, consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help me produce and continue to improve Law Dork in the months to come.

Thank you.

![14 Not content to rest on the Court’s argument, which relies on the Court’s understanding of the original meaning of the Appropriations Clause, four Justices advance an entirely different rationale, namely, that congressional practice in the ensuing centuries supports the consti- tutionality of the CFPB’s scheme. Ante, at 1 (KAGAN, J., concurring). This argument is doubly flawed. First, the concurrence cannot point to any other law that created a funding scheme like the CFPB’s. Second, as explained by Justice Scalia, the separation of powers mandated by the Constitution cannot be altered by a course of practice at odds with our national charter. See NLRB v. Noel Canning, 573 U. S. 513, 571–572 (2014) (opinion concurring in judgment). “[P]olicing the ‘enduring struc- ture’ of constitutional government when the political branches fail to do so is ‘one of the most vital functions of this Court.’ ” Id., at 572 (quoting Public Citizen v. Department of Justice, 491 U. S. 440, 468 (1989) (Ken- nedy, J., concurring in judgment)). 14 Not content to rest on the Court’s argument, which relies on the Court’s understanding of the original meaning of the Appropriations Clause, four Justices advance an entirely different rationale, namely, that congressional practice in the ensuing centuries supports the consti- tutionality of the CFPB’s scheme. Ante, at 1 (KAGAN, J., concurring). This argument is doubly flawed. First, the concurrence cannot point to any other law that created a funding scheme like the CFPB’s. Second, as explained by Justice Scalia, the separation of powers mandated by the Constitution cannot be altered by a course of practice at odds with our national charter. See NLRB v. Noel Canning, 573 U. S. 513, 571–572 (2014) (opinion concurring in judgment). “[P]olicing the ‘enduring struc- ture’ of constitutional government when the political branches fail to do so is ‘one of the most vital functions of this Court.’ ” Id., at 572 (quoting Public Citizen v. Department of Justice, 491 U. S. 440, 468 (1989) (Ken- nedy, J., concurring in judgment)).](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4VA_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4e5b5a5e-601d-44f4-9350-7a26b8e5b528_1194x636.png)

love your posts which yep, I've paid for. And lovely to see the interesting crack in the idea of originalism. And really lovely to see the point that the Separation of Powers applies to the frickin judiciary.

Thank you for the hard work you continue to do reporting what is going on in the Supreme Court.