A federal judge refused to block the new Title IX rule, then an appeals court stepped in

Update: Judge Axon would have allowed the rule, which includes LGBTQ protections, to go into effect, but the appeals court issued an "administrative injunction" blocking it.

A federal judge broke ranks with several of her colleagues on Tuesday, harshly rejecting the request from four southern states and a handful of organizations to block the Biden administration’s new sex discrimination educational rule before it is set to go into effect on Thursday.

“The evidentiary record is sparse, and the legal arguments are conclusory and underdeveloped,” U.S. District Judge Annemarie Axon wrote in rejecting, for now, the arguments advanced by Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, as well as the Independent Women's Law Center, Independent Women's Network, Parents Defending Education, and Speech First, Inc.

Axon, a Trump appointee to the Northern District of Alabama, is the first federal district court judge to deny a request for a preliminary injunction against enforcement of the new rule, issued under Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972. The ruling comes as the U.S. Supreme Court is considering the Justice Department’s request to partially stay injunctions issued in two other cases.

The sex discrimination rule has primarily been challenged for its inclusion of gender identity in its definition of sex discrimination and sections addressing “sex-separated facilities” and “hostile-environment harassment,” both of which include provisions that would provide protections to transgender students. The lawsuit before Axon also challenges the new rule’s process for how schools can and must address complaints of sex-based harassment.

Axon, at this point in the case, rejected all of those arguments in a 122-page opinion that took umbrage at the plaintiffs’ briefing and arguments as inadequate — or even misleading — at every turn.

The bottom line — and a sign of how different Axon’s decision was from the others — was summed up in a section where the Alabama judge rejected the plaintiffs’ claim that the section of the rule addressing sex-separated facilities violates the Administrative Procedure Act for being arbitrary or capricious.

“At their core, Plaintiffs’ arguments are not that the Department exceeded the zone of reasonableness,” Axon wrote, referencing the standard for judging whether a rule violates the APA, “but rather, that Plaintiffs disagree as a policy matter.”

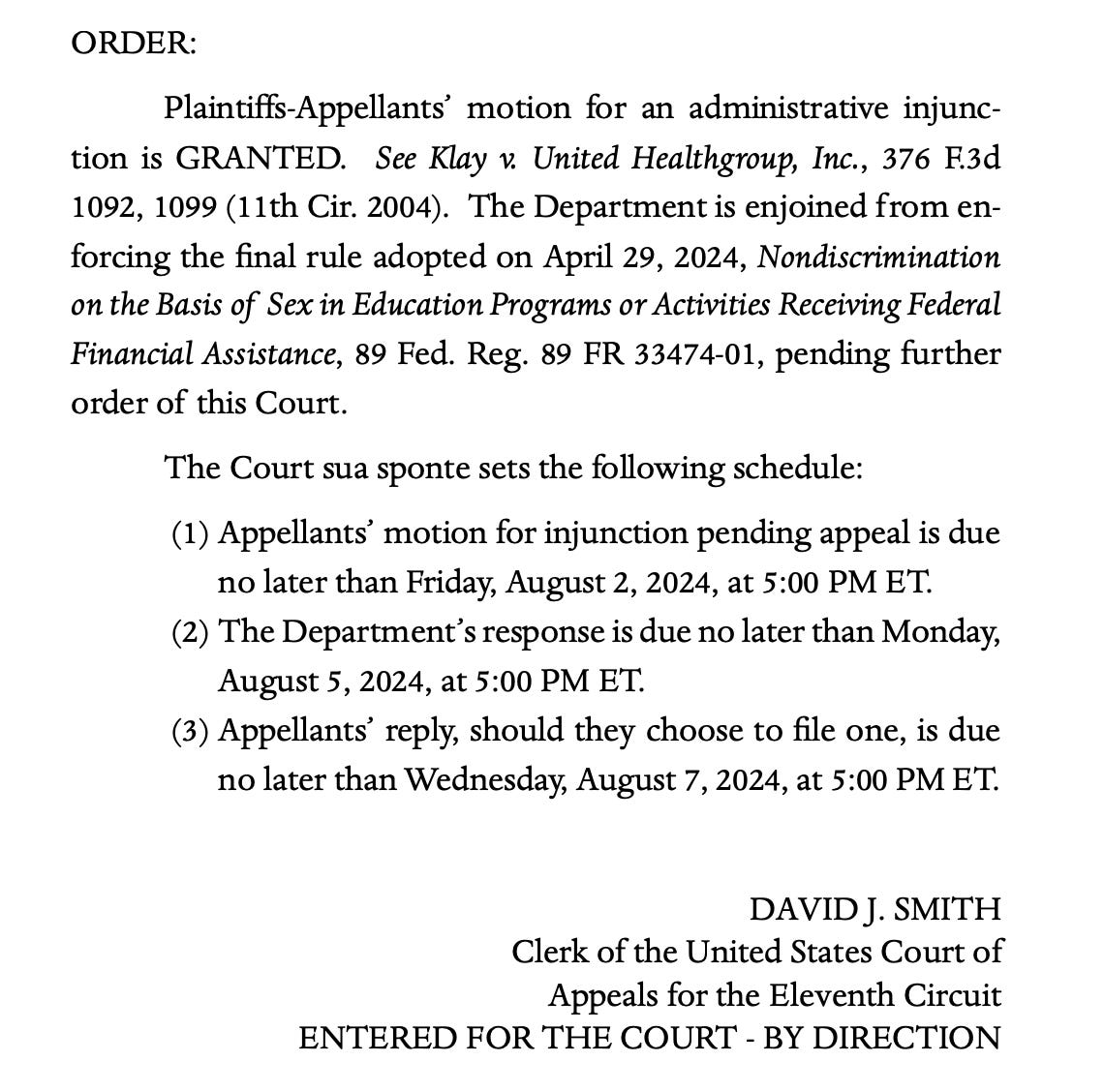

[Update, 12:15 a.m. July 31: Lawyers for the plaintiffs have filed an “emergency motion for administrative injunction” at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. The motion, filed at 11:11 p.m. July 30, asks the court for a ruling by July 31.]

[Update, 7:50 p.m. July 31: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit granted the plaintiffs’ request for an “administrative injunction” in an unreasoned order that set a timeline for briefing on a request for an injunction pending appeal that the plaintiffs have said is forthcoming but that is yet even to be filed.

The order — for now — blocks the rule as requested by the plaintiffs and effectively wipes out Axon’s decision.

Notably, the second sentence of the court’s order left its scope unclear. The order, by its terms, could be read as granting a nationwide injunction — despite the fact that the plaintiffs were only seeking an injunction that would cover Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

In a “notice of compliance” filed by the Justice Department about 90 minutes after the court issued its order, DOJ lawyers noted the geographic limits of the plaintiffs’ request and wrote, “Defendants do not understand the Court to have granted additional relief beyond that requested by plaintiffs, and therefore understand the administrative injunction to apply only within the plaintiff states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Defendants will comply with the injunction accordingly.”

With the Eleventh Circuit’s order and a Wednesday morning order from U.S. District Judge Jodi Dishman, a Trump appointee, blocking the rule in Oklahoma, the rule — going into effect on Thursday — is currently blocked in 26 states: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming.]

Law Dork has covered the challenges to the Title IX rule in depth. Check it out, and share this report with friends and colleagues.

Shoddy plaintiffs’ lawyering

Axon’s decision is an extraordinary ruling that stands out from the others, which Law Dork has covered in depth, for its willingness to engage with case law and the rule — and not, as others have done, accept conclusory arguments.

Those arguments made by the challengers to rule boil down to a view that protecting against gender identity discrimination amounts to a dramatic change in Title IX. They also rely on a claim that the U.S. Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in 2020’s Bostock v. Clayton County, in which the court held that the sex discrimination ban in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 includes a ban on sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination, is more or less irrelevant to courts’ analysis of Title IX.

Axon goes through all of that and much more, but, from the start, she also made abundantly clear that she just thought the plaintiffs’ lawyers did a shoddy job.

Language used by Axon in describing the arguments of the plaintiffs include “misplaced,” “misleading,” “misrepresent,” and “misleadingly.”

At oral arguments, according to the docket, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall and Solicitor General Edmund LaCour represented the state plaintiffs and Cameron Norris and Thomas Vaseliou from Consovoy McCarthy PLLC represented the organizational plaintiffs.

“Although they are challenging only some of the amended regulations, Plaintiffs reference ‘the rule’ throughout their brief and during oral argument,” Axon wrote. “There is no explanation or argument as to why the Final Rule should be considered collectively in some places and individually in others. The approach is unfortunate: it serves no appropriate purpose and intentionally burdens the court, which must attempt to discern the arguments and evaluate whether the extraordinary relief sought is warranted ‘without the luxury of abundant time for reflection.’”

This understanding of what the plaintiffs were doing alone distinguished Axon from her colleagues hearing Title IX rule challenges.

Despite the fact that courts in other instances — such as challenges to bans on gender-affirming medical care for minors — require plaintiffs to justify each and every line of a law that they are challenging, judges in the Title IX rule cases have eagerly been blocking the entire 423-page rule despite the fact that plaintiffs, as noted, are often only challenging three provisions in the rule.

On Tuesday, Axon did the opposite — declining to block any of the rule and later denying a request to block the law while the plaintiffs appeal Tuesday’s ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. [Update, 12:15 a.m. July 31: Lawyers for the plaintiffs have filed an “emergency motion for administrative injunction” at the Eleventh Circuit. The motion, filed at 11:11 p.m. July 30, asks the court for a ruling by July 31.]

In her extensive opinion, Axon criticized the failure of plaintiffs to even explain how and where their preliminary injunction request connected to their complaint in the case. “[B]ecause the court serves only the role of neutral arbiter of the matters presented, … it may not concoct arguments where Plaintiffs have fallen short,” she wrote.

Additionally, Axon continued, “many arguments in Plaintiffs’ motion are inadequately briefed,” citing eight examples and concluding, “With each failure to provide a meaningful explanation, Plaintiffs forfeit the argument.” (Nonetheless, throughout the opinion, Axon noted conditionally at least five times how, “even if” plaintiffs had met one requirement for relief, they nonetheless still fell down on other grounds.)

Ultimately, what Axon did is actually challenge the weak claims made in the plaintiffs’ lawsuit — not rule on anti-trans vibes.

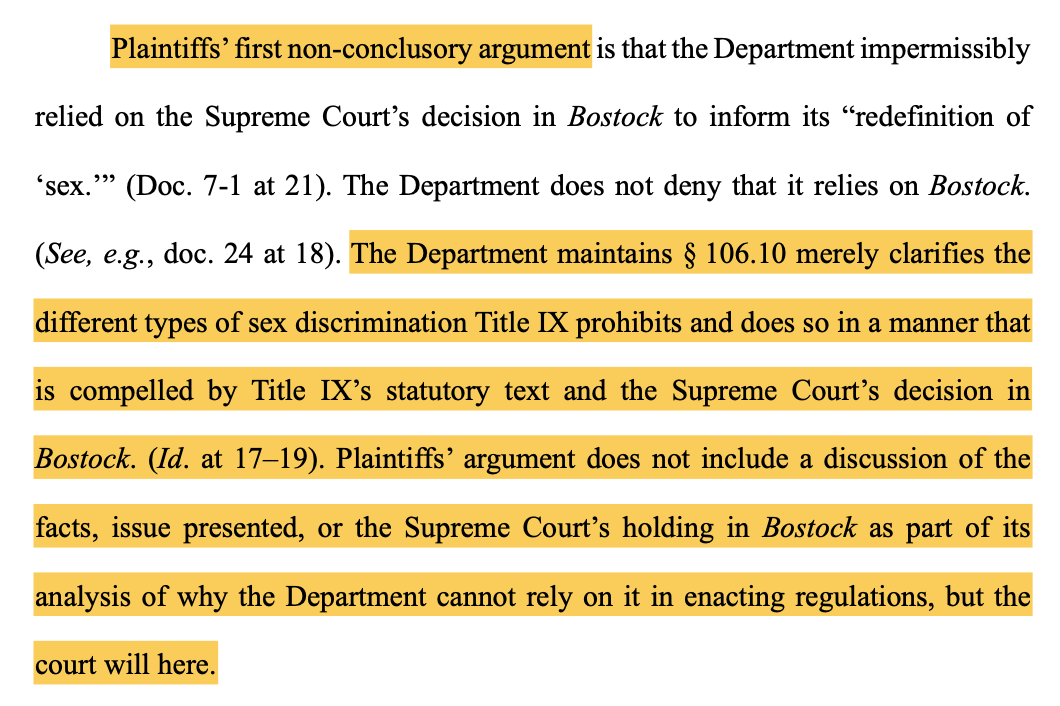

On Bostock

When it came to the legal heart of the matter, Axon — again, unlike the other judges to hear the Title IX rule challenges — appears actually to have read Bostock.

Axon went on to describe the case and its meaning, whereas other judges have simply taken plaintiffs’ position that, since the Bostock court said it was not deciding whether the reasoning of the case applied to other laws and provisions (the norm for all court decisions), that settles the question in the negative. (It doesn’t.)

She then addressed the plaintiffs’ treatment of recent Eleventh Circuit’s decisions involving transgender rights. Of one case — Adams v. School Board of St. Johns County, Florida — involved a trans-exclusive restroom policy at a school. As to that, Axon had to explain that the plaintiffs were “incorrect” about what the Eleventh Circuit decision was even discussing.

“The discussion Plaintiffs cite came from the part of the Adams opinion addressing whether the student could establish an equal protection violation, not a Title IX violation,” she wrote.

As to the more recent decision upholding Alabama’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors as likely constitutional — Eknes-Tucker v. Governor, State of Alabama — Axon wrote, “The court has carefully reviewed Eknes-Tucker and is unable to find any language limiting Bostock exclusively to Title VII.“

Contrary to the plaintiffs’ arguments, Axon wrote that “[t]he important lesson to be taken from Eknes-Tucker is the necessity of carefully examining the relevant statutory language and factual context before using legal standards from one statute to interpret a different statute.” To that, she concluded, “That careful examination is precisely what Plaintiffs failed to do in their request for preliminary injunctive relief.”

So, what did Axon decide?

Ultimately, Judge Annemarie Axon found that any part of the rule she enjoined could be severed from the remainder of the rule but that the plaintiffs did not show — at this stage — that they are likely to succeed on any of their claims, so it didn’t matter.

Specifically, she found that they did not show they were likely to succeed on the merits of their claim that including “gender identity” in the definition of sex-based discrimination was contrary to law or arbitrary or capricious in violation of the APA.

She also found the same as to their claim against the hostile-environment harassment part of the rule. As to those arguments, she also similarly critiqued plaintiffs’ claims regarding relevant Supreme Court and Eleventh Circuit case law — finding their arguments insufficient at best.

Finally, as to the process for complaints under the new rule, Axon found that the plaintiffs had not shown they were likely to succeed on any of the aspects challenged — although she did find that plaintiffs were “closer” to carrying their burden as to one provision (relating to the burden of proof required as part of such proceedings). But, even there, she did not find that they met their burden.

Finally, Axon also had harsh words as to another consideration when a plaintiff is seeking a preliminary injunction — whether they would face irreparable harm without an injunction. This was another “even if” section, in essence — even if plaintiffs showed they are likely to succeed, which they didn’t, they failed here, too.

“As an initial matter, Plaintiffs have not acted with urgency in this case thus far,” Axon noted in leading off this section — and detailing the “leisurely” schedule plaintiffs sought for moving forward with their case.

Additionally, she noted a matter covered extensively at Law Dork — the Kansas federal court injunction from U.S. District Judge John Broomes, which included blocking enforcement of the rule at schools nationwide attended by the members of two plaintiff groups in that lawsuit and the schools attended by children of members of a third plaintiff group.

Of that injunction, Axon wrote:

In other words, Axon was not happy with how the plaintiffs described that injunction — and she concluded the Kansas court’s injunction reduced the irreparable harm that the plaintiffs in front of her in Alabama could claim.

To let you know how frustrated Axon was with the plaintiffs by page 112 of her opinion, the next line began, “Turning to the arguments Plaintiffs did make ….” Those arguments for “irreparable harm” included claims about the injuries the states would face if the rule went into effect. To those, she largely concluded that their arguments were tied to the fact the enforcing the rule would mean enforcing an illegal rule. Since she concluded they were not — at this point — likely to succeed on the merits, though, those arguments of irreparable harm also must fail.

In sum: The rule would be severable if the plaintiffs did succeed on any claims, but Axon found that the plaintiffs did not show they are likely to do so and, in any event, they also did not show that they will suffer irreparable harm if they don’t get an injunction while the litigation is ongoing.

Closing thoughts

Axon looked at the law, rule, and arguments; was not distracted by the fact that the rule seeks, in part, to provide protections to transgender people; and did her job.

In rejecting the plaintiffs’ argument that the rule involves a so-called “major question,” Axon perhaps put it best.

“[T]hey provide no evidence that sex-separation of bathrooms is of such importance that it rises to a major question, instead stating in a conclusory manner that it ‘plainly’ does,” Axon wrote. “The court declines to issue extraordinary relief based on such a conclusory argument.”

Thank you for the detailed explanation.

It is refreshing to find a Trump-appointed Judge that is actually doing their job and not being a fanatical partisan hack. Sadly. It’s also vanishing rare . . .

Absolutely refreshing. The Federalist Society must be beating its head against the wall for recommending her to trump.