Where are the people the Trump administration has deported?

The Trump administration's aggressive immigration deportation efforts often have been carried out illegally. What has happened to the people at the center of the cases?

In its first 150 days, the second Trump administration has used immigration authorities to aggressively deport people — including by sending them to foreign prisons and to countries where they had no prior connection. And, though the executive has extensive power over immigration matters, these deportations have been carried out at times in violation of the Constitution, the laws of the United States, court orders, and court-approved settlements.

Many of these people have, essentially, been disappeared — with the Trump administration arguing that courts lack authority to issue orders as to people outside of U.S. airspace and that the government itself lacks the ability to bring back those people it sent to a foreign prison.

Just over 50 days into his time back in office, President Donald Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act — a 1798 law only previously invoked during wartime — to try and rapidly deport Venezuelans who the administration decided were members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang. In doing so, the Trump administration provided even less process than was given to Nazis who the U.S. was seeking to depart during World War II — a point Judge Patricia Millett raised in arguments over the president’s actions at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit on March 24.

The AEA proclamation is just one front in this anti-immigrant effort, spearheaded by Stephen Miller with support from several of Trump’s cabinet members. Among its challenged actions, the government sent three flights to El Salvador on March 15, including two with people aboard under the purported authority of Trump’s AEA proclamation. The Trump administration has sent people to Guantanamo Bay before trying to have the Defense Department send them elsewhere. It also reportedly planned to send a flight to Libya and/or Saudi Arabia until a court intervened. And, it did send a flight out of the U.S. that was bound for South Sudan but landed at a military base in Djibouti after court intervention. (In addition to the deportations, there are also the many AEA challenges as to those in the U.S. currently and the efforts to revoke student visas and deport them and recently graduated students. Law Dork has and will continue to cover those cases, but they are not the focus of this report.)

Individuals and their lawyers have challenged these deportations in multiple lawsuits as to classes of people and as to specific individuals. Judges in these cases have either ordered the government to take action to remedy a found legal violation or at least raised questions about the administration’s actions.

Law Dork can report that two such orders have resulted in the return of a person to the U.S. Both Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the Maryland man sent to El Salvador’s CECOT prison in an “administrative error,” and O.C.G., a gay man sent into hiding when the Trump administration deported him to Mexico, have been brought back to the U.S. in the past two weeks.

But, that is not true for many others.

So, almost five months into the Trump administration: Where are they?

Members of the AEA CECOT class — the people sent to CECOT under Trump’s AEA proclamation — are, we believe, still in El Salvador’s CECOT prison. There were materials turned over in the challenge pending before D.C. District Court Chief Judge James Boasberg over that class under seal and subject to redactions, but his ruling stated that the class in question was “currently” in CECOT.

Although Boasberg had set a June 11 deadline for the Trump administration to explain how it would provide the ability for those people to seek habeas relief, a D.C. Circuit panel “administratively stayed” that order on June 10, as I covered at Law Dork.

So far as we know then, the people on those first two planes likely remain in CECOT — although Boasberg found that, based on a declaration from a State Department official, the Trump administration claims that both the “detention” of CECOT class members and their “ultimate disposition” as to that prison “are matters within the legal authority of El Salvador.” Although raised in Boasberg’s discussion of “constructive custody” for habeas purposes, the information is relevant here as to figuring out whether those people sent to CECOT remain there.

According to the Trump administration, it is not their call.

The third March 15 plane to CECOT, the Trump administration has insisted, contained no one deported under the AEA. These people, per the Trump administration, were “noncitizens subject to final orders of removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act.” Aside from later raised cases, those people are likely still in CECOT — although, for similar reasons as with the AEA CECOT class, there is no real reason to know that outside of specific cases where questions have led to further information being provided.

Among those people on the third flight was Kilmar Abrego Garcia, deported in an “administrative error” but now returned to the U.S. and indicted in Tennessee in a political move that reportedly led to the abrupt resignation of the head of the criminal division of the Nashville U.S. Attorney’s Office. Abrego Garcia’s removal-in-error case garnered significant national attention but little public movement from the Trump administration to adhere to U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis’s April 4 order that the administration “facilitate” the return of Abrego Garcia.

But, behind the scenes, the administration was apparently cooking up the Tennessee case and, on June 6, the case was unsealed as Abrego Garcia was returned to the U.S. He is currently in Tennessee, where a detention hearing is set for Friday.

Before I move on, however, I would like to note the administration’s disingenuous-at-best, lawless-at-worst actions since the unsealing of the Tennessee case in federal court in Maryland, where Xinis was hearing the case about Abrego Garcia’s deportation.

On June 6, DOJ lawyers told Xinis, “Defendants hereby provide notice that they have complied with the Court’s order, and indeed have successfully facilitated Abrego Garcia’s return,“ as part of a request that Xinis stay all deadlines in the Maryland case. Needless to say, Abrego Garcia’s lawyers did not agree, responding over the weekend that “to characterize the Government as having ‘complied with the Court’s order’ is pure farce.” They continued, highlighting the government’s intransigence in the case and then adding:

In its latest act of contempt, the Government arranged for Abrego Garcia’s return, not to Maryland in compliance with the Supreme Court’s directive to “ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador,”[1] but rather to Tennessee so that he could be charged with a crime in a case that the Government only developed while it was under threat of sanctions. That Tennessee indictment was filed under seal on May 21,[2] yet six days later the Government continued to insist to this Court that it “do[es] not have the power to produce him,” ECF No. 165 at 5.

1 Noem v. Abrego Garcia, 145 S. Ct. 1017, 1018 (2025).

2 See ECF No. 3 in United States v. Abrego Garcia, No. 3:25-cr-00115 (M.D. Tenn.).

Opposing the government’s request for a stay, the lawyers continued, “The Government’s conclusory professions of compliance are entitled to no deference, and Plaintiffs are entitled to examine in discovery whether Government officials acted in good faith.“

They concluded:

Xinis is yet to rule on that request.

Elsewhere in federal court in Maryland, U.S. District Judge Stephanie Gallagher has been overseeing a class-action settlement agreement reached during the Biden administration requiring the government to rule on the class members’ asylum applications prior to any removal. Cristian, however, was sent to CECOT on one of the AEA planes before any such ruling. As I’ve covered previously, Gallagher found on April 23 that the government’s actions were not allowed under the settlement and ordered the government to “facilitate” Cristian’s return to the U.S.

As of June 6, Mellissa B. Harper, the acting deputy associate director of Enforcement and Removal Operations at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in the Department of Homeland Security, stated that her “understanding” was that Cristian remained at CECOT, per the Salvadoran government via the U.S. Embassy.

However, Harper continued:

As Cristian’s lawyers noted on June 10, though, the recent return of Abrego Garcia to the United States raises questions about Harper’s second claim.

“The government’s return of Mr. Abrego Garcia confirms they have the power to return individuals detained in El Salvador, despite their assertion to the contrary,” class counsel Brian Burgess with Goodwin wrote. “Plaintiffs raise this development, as 1-1/2 months have passed since this Court ordered that the government facilitate Class Member Cristian’s return to the United States.“

Third country removals

Then, there is the third-country removals case, D.V.D. v. DHS. This is the case over attempts by the government to deport people to a country other than their home country or another country in which the person has legal status. To do so, U.S. District Judge Brian Murphy ordered, certain process must be provided so that the person has the ability to challenge their removal to that third country.

Since then, the parties have returned to court three times regarding allegations that the Trump administration is violating that preliminary injunction — and had significant follow-up litigation surrounding one specific plaintiff in the case. The first time, the administration sent people to Guantanamo Bay and then claimed it was the Defense Department sending them to a third country. That led to Murphy’s first “clarification” of his injunction: No, the Trump administration can’t do that without still adhering to the injunction’s terms.

There were specific questions raised as to one of the plaintiffs. O.C.G., a gay man, was sent into hiding, his lawyers said, due to the Trump administration’s actions deporting him to a third country where he previously had faced violence. On May 23, Murphy ordered that the government “facilitate” his return, and the Justice Department told Murphy five days later that DHS was “working … to bring O.C.G. back to the United States.“

That has happened, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs in the case told Law Dork. O.C.G. is in immigration detention in Arizona, one of the lawyers for the case, Trina Realmuto, the executive director of the National Immigration Litigation Alliance, said on Wednesday.

For the rest of the class, though, the Trump administration has continued to seek third country removals with less process provided than Murphy ordered was necessary.

When news reports emerged that the administration had planned deportations to Libya and/or Saudi Arabia, the plaintiffs’ lawyers went back to Murphy, who issued another “clarification” order. “If there is any doubt—the Court sees none—the allegedly imminent removals, as reported by news agencies and as Plaintiffs seek to corroborate with class-member accounts and public information, would clearly violate this Court’s Order,” he wrote on May 7.

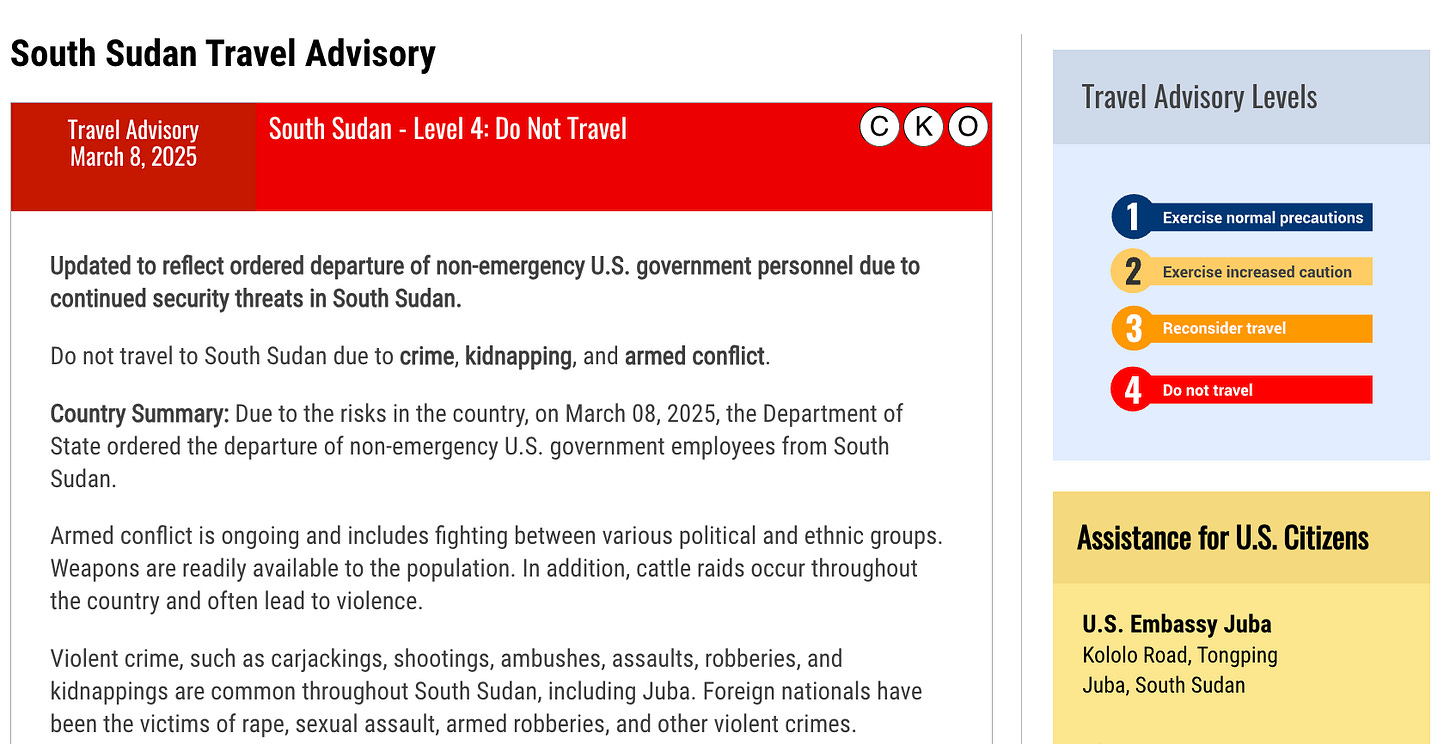

Less than two weeks later, the plaintiffs’ lawyers were back in court on May 20. This time flights had already left the U.S., the lawyers believed, with a destination of South Sudan — a country where the Trump administration had pulled all non-emergency personnel due to the dangerous conditions. Murphy issued a quick order that the administration “maintain custody and control of class members currently being removed to South Sudan or to any other third country” until he could issue a further ruling.

That led the flight to land at a military base in Djibouti. After a further hearing the next day, Murphy concluded that the Trump administration’s actions sending the people on the flight violated his injunction because they had not been given a sufficient opportunity to challenge their removal to South Sudan. As such, he ordered that each person “be given a reasonable fear interview in private, with the opportunity for the individual to have counsel of their choosing present during the interview, either in-person or remotely, at the individual’s choosing,“ among other protections. Murphy allowed that the Trump administration could carry out those interviews in Djibouti or back in the U.S., so long as certain protections were maintained.

It has now been three weeks since that order, and, as of June 9, the people remained in Djibouti. In a June 2 filing, DOJ stated that “all eight aliens remain in the custody of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in Djibouti.” In a June 9 filing, DOJ stated, “All detainees that arrived in Djibouti remain there in the custody of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).“

Where are they?

According to ICE’s Harper, who submitted a declaration in the case dated June 4, they are in a cargo shipping container on the base.

Harper went on to describe the conditions in Djibouti, noting cramped sleeping quarters for the ICE officers and that “ICE personnel had to interrupt the flight and disembark in Djibouti without being on anti-malaria medication for at least 48-72 hours prior to arrival, as recommended by medical professionals.” She also noted that ICE “officers were warned by U.S. Department of Defense officials of imminent danger of rocket attacks from terrorist groups in Yemen.“

Harper did not mention the worse conditions in the country where the U.S. was trying to deport these people.

These are not all of the cases, let alone the questionable — or even illegal — deportations carried out by the Trump administration. The New York Times, to give just one example, reported on a case where claimed “administrative errors” led to a person’s removal. Jordin Melgar-Salmeron’s case is ongoing before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit — and there are doubtless many more.

These cases that have captured our attention, however, do show how broad the Trump administration has gone already to deport people — and how much success they have had at sending people out of the country, even if it is done illegally.

Thank you for this!

I worry that we focus on one person, and yes, Trump et al were forced to return him to the states. But that's a token at best. What about all the others?

Like the children Trump forcibly separated from parents in his first term, they deliberately don't keep good records so that their illegal acts can't be undone.

We need to track them all — and probably not just the ones who have been deported, or sent to a third-country prison, but the ones who are in custody here.

Where are the people?

As others note, thank you for in in-depth analysis. This is not about one person or even a few people. It is about many people illegally and inhumanely treated. This is not just about Trump. This is about the United States of America. The world has a reason to treat us as pariahs.