University drag ban arguments focus on SCOTUS nondiscrimination policy decision

In response to questions from Judge James Ho, the student group's lawyer, from FIRE, said he was not there to "defend" 2010's Christian Legal Society v. Martinez decision.

The only way that Judge James Ho apparently would be open to drag being protected on West Texas A&M University’s campus is if Christian student groups are allowed to discriminate against gay students.

Of course, if that happened, the far-right Trump appointee would doubtless find another reason to support a public university’s campus drag ban. But, for Ho, first things first.

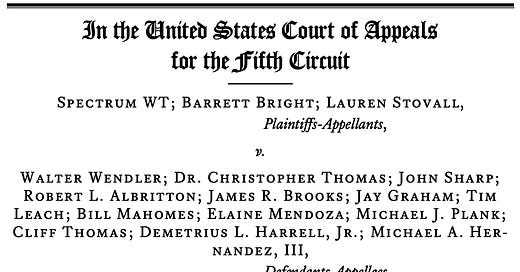

To that end, he spent nearly 45 minutes on Monday upending the First Amendment in oral arguments at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit over the university LGBTQ student group’s attempt to hold a charity drag show on campus.

In response to Spectrum WT’s plans, West Texas A&M’s president, Walter Wendler, issued a drag show ban on campus, which he admitted was likely unconstitutional, leading to this lawsuit. More than a year later, though, the ban remains in effect.

On Monday, Ho quickly turned the arguments to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez. In that case, a public university’s “all-comers” policy — that a student group seeking the benefits of a public university’s recognition must allow all to join the group — was upheld against a First Amendment challenge as being a reasonable, viewpoint-neutral policy.1

It was, at its base, a ruling that a public university can require recognized student groups to adhere to a nondiscrimination policy.

On Monday, though, Ho described it as an edict from the high court that “we have to defer to university administrators, particularly when it comes to issues of inclusion.”

In a strange twist due to the lawyers on the case, Ho received virtually no opposition to his arguments opposing, and even seeking to overturn, the CLS v. Martinez decision — a legal change that could even further endanger nondiscrimination efforts on college campuses. Instead, the lawyer for the student group simply — and correctly — distinguished the two cases.

Ho’s performance on Monday was, in part, an effort to convince Judge Leslie Southwick, a George W. Bush appointee, to join him in affirming U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s outlier ruling that drag is not protected expression and that Wendler’s ban is not content-based discrimination and that, as such, Wendler was within his right to ban drag on campus.

Whether it will work or not remains to be seen. Southwick asked far fewer questions on Monday, including about the differences between the CLS case and the facts here. I’m not sure that the third member of the panel — Judge James Dennis, a Clinton appointee — asked any questions.

The ban, CLS, and Ho

West Texas A&M’s drag ban issued by Wendler is a plainly unconstitutional action, both viewpoint-based and content-based discrimination. The constitutional offensiveness is made all the more so by the fact that this ban is ongoing — preventing future First Amendment activities of Spectrum WT. Known as a prior restraint, this is one of the most offensive of actions under the First Amendment.

And yet, more than a year later, no one — including the U.S. Supreme Court — has stopped Wendler.

Ho’s great animosity for the CLS v. Martinez decision was apparent throughout the arguments. In Ho’s varying, yet repetitive, questions on Monday, he left little doubt that he believes it is far worse for Christian student groups seeking public university recognition and university funding to be forced to allow gay members — i.e., other members of the university community — than it is for a university administrator to ban all drag shows on campus because he personally is offended by them.

J.T. Morris, a senior attorney at Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) who is representing Spectrum, told Ho that “CLS is apples to oranges” from Spectrum’s case and Wendler’s actions, which he described as being clearly unconstitutional on these multiple grounds.

“When the government makes a determination, a subjective determination, that speech is offensive and restricts it on that basis, that is viewpoint discrimination,” Morris “We cannot allow the government, and the First Amendment does not allow the government, to use the subjective term ‘offensive’ to restrict speech.”

Equating CLS v. Martinez, though, Ho said, “The school [there], rightly or wrongly, decided that the Christian group — and any group that excludes members based on a criteria — that's ‘offensive,’ that is not inclusive, it's ‘offensive’ to the university's interests,” adding that the “Supreme Court bound us to defer” to that decision.

That should control here, too, Ho insisted.

“This case is not about students excluding anybody,” Morris replied. “This case is about the university excluding students from a public forum.”

“They are actually being treated better than CLS,” Ho claimed.

“I’d have to disagree with you, your honor,” Morris said, citing Wendler’s actions banning First Amendment expressive activity.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, concurring in the CLS case decision, wrote that “an otherwise qualified and relevant speaker may not be excluded because of hostility to his or her views or beliefs.”

That sums up the distinction between the CLS case and Spectrum WT case. That could and should be the end of it.

When Ho later argued that CLS “endured a number of prior restraints” because of benefits it would not get if it could not be a recognized group, Morris shot back that — regardless of whether the court holds that the policy is viewpoint-based discrimination — it was a content-neutral policy that led to those results for CLS, whereas this is a content-based restriction by Wendler and West Texas A&M University.

Playing with FIRE

In a part of this argument over the CLS case that should not be glossed over, Ho repeatedly tried to get Spectrum’s FIRE lawyer to agree that CLS v. Martinez should be overruled. In doing so, Ho went so far as to ask whether, if the Fifth Circuit affirms Kacsmaryk’s decision, Spectrum and FIRE will seek to have CLS v. Martinez overruled by the Supreme Court.

FIRE, unlike many of those who would generally defend challenges to drag performers, is not seen as a liberal or left-leaning organization. To the contrary, FIRE is generally seen as a more conservative or libertarian organization that is often on the conservative side of campus “free speech” debates.

As such, it was significant that Morris told Ho, “I am not here to defend CLS.”

Morris not only never defended CLS v. Martinez, he also left open the possibility that Spectrum, with FIRE lawyers representing it, would ask today’s far more conservative Supreme Court to overrule that decision if the case gets to the Supreme Court.

When the Supreme Court issued the decision in CLS v. Martinez back in 2010, the ACLU praised the ruling, with then-legal director Steven Shapiro noting, “While all student groups are free to meet and hold their own beliefs, a public university has the right to enact policies that refuse to officially recognize and fund groups that deliberately exclude other members of the student body.”

On Monday, in contrast, the nondiscrimination element of the CLS case — a clear distinction from the Spectrum WT case — was hardly referenced and, when it was, it was done so only indirectly (as in when Morris mentioned that the CLS case was about “students excluding” other students).

Now, it is entirely defensible that the focus of an advocate arguing in the Fifth Circuit would not be on the nondiscrimination principle in the CLS decision. Strategy-related decisions are difficult, and anyone arguing in the Fifth Circuit is not going to be leaning into a liberal position.

Nonetheless, the possibility that FIRE could use this case to seek to overturn that precedent is something else altogether — and a move that LGBTQ advocates should face and address forthrightly and before it happens.

Full disclosure: Several years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision, I opposed the Christian Legal Society’s exclusionary policies while a law student at The Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law.

I believe Erin Reed had in the past highlighted the problems of FIRE being the ones to challenge this as well.

This isn't apples to oranges, it's apples to chickens! Just because some people eat both doesn't mean they're even remotely the same thing. This is such a sketch argument that anybody would be tempted to lean into a conspiracy theory that Wendler and Ho orchestrated this drag ban as a way to overturn the CLS decision. (I know that's almost certainly not the case, just smells like it awfully hard...)