Trump ends federal contractor civil rights order with roots that go back to FDR

In revoking Executive Order 11246, Trump took aim at history and efforts to combat discrimination. Also: Trump's effort to end birthright citizenship is blocked for now.

On January 21, President Donald Trump revoked an executive order that has guided federal contractor nondiscrimination policy for nearly 60 years — and that has a history that reaches back nearly another 25 years.

The move from Trump revoking Executive Order 11246 was part of an expansive executive order aimed at eliminating diversity programs across the government, in federal contractors’ businesses, and in all private business. That order, in turn, has been a part of a government-wide move to reverse former president Joe Biden’s orders supporting diversity and declare that efforts supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion are — depending on the order — “illegal and immoral” or not “American … values.” All of those orders, in turn, work in tandem with Trump’s other executive orders aimed at Trump exerting more control over the federal workforce.

It is nothing less than an effort to erase as much progress as possible achieved in making workplaces safer and more equitable for people of color; for women; for LGBTQ people; and, somehow, for people with accessibility needs required under federal law.

The immediate effects of the Trump administration’s anti-diversity efforts were perhaps most starkly seen in the news that all employees of all Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Offices across the federal government were being placed on paid leave this week following a memorandum from Charles Ezell, the acting director of the Office of Personnel Management, to the heads of agencies and departments on January 21.

According to the memo, department heads were to “[s]end a notification to all employees of DEIA offices that they are being placed on paid administrative leave effective immediately as the agency takes steps to close/end all DEIA initiatives, offices and programs.” According to a template letter attached to the memo, the employees were also to be told, “Your email access will be suspended. Please make sure that your address of record and contact information are current with your agency.“

This was quickly followed on Wednesday by the so-called snitch email that acting department heads were directed to send out by Ezell, a data and analytics employee at OPM who Trump designated as the acting head of the office on January 20. Versions of the email circulated from many departments on social media Wednesday.

The government employee restrictions, however, were just the start.

The January 21 order revoked an executive order signed by then-president Lyndon Baines Johnson whose history is inextricably intertwined with America’s civil rights movement.

Although revoking Johnson’s order does nothing to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its workplace protections, Executive Order 11246 contained additional requirements and provided the federal government with a strong tool to more directly address the nondiscrimination practices of the many employers with federal contracts.1

Finally, and though beyond the scope of this report, do note that Trump’s January 21 order goes much further than revoking Executive Order 11246. Among other provisions, it has an entire section purporting to “Encourag[e] the Private Sector to End Illegal DEI.“ In short, this is just the beginning of the coverage of this order and its possible harms to workplace diversity.

What is this attack?

Before we look back, let’s first just be clear: The policies the Trump administration is attacking are very much the American values advanced, albeit imperfectly, over the past 60 years — including when former president George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law.

Here’s how a 2024 federal report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office put it:

There should be nothing controversial about any of this. If certain policies or programs go too far, review them and fix them, but the fundamental basis for and nature of these policies began with the Civil War Amendments and were forged into modern America’s laws in the Civil Rights Era and the time since.

But now, with a handful of orders in his first two days in office, Donald Trump wants to hobble that legacy — and eliminate any ongoing efforts to help ensure a diverse workforce.

What is the history?

As Trump sits in the Oval Office signing these orders, he is sitting in the room where then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt was told more than 80 years ago that an executive order was needed to stop military contractors from discriminating against Black people seeking jobs.

I detailed this history in an extensive report I wrote at BuzzFeed News more than a decade ago, written in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The idea for that march, I explained, drew its inspiration in part from a march planned more than 20 years earlier.

Called for by labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, the plan would be, Randolph told a crowd in Savannah, Georgia, in December 1940 to "gather[] 10,000 Negroes to march on Washington to demand jobs in the defense industry."

Six months later, the plan had moved forward for a July 1 march, with Randolph, who was the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, working with Walter White of the NAACP and others to organize the event.

After a failed attempt by then-first lady Eleanor Roosevelt to get Randolph to call off the march, he and White ended up sitting face to face with the president in the Oval Office on June 18, 1941.

As Jervis Anderson detailed in his biography of Randolph:

One week later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, declaring it to be “the policy of the United States” that all Americans — “regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin“ — must be a part of “the national defense program“ because of “the firm belief that the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders.“

The nondiscrimination order only applied to defense-related industries at first, although Roosevelt later expanded that. A little less than 15 years later, after signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, Johnson expanded the order further, put responsibility for enforcing it in the Labor Department, and set it on its modern course in signing Executive Order 11246.

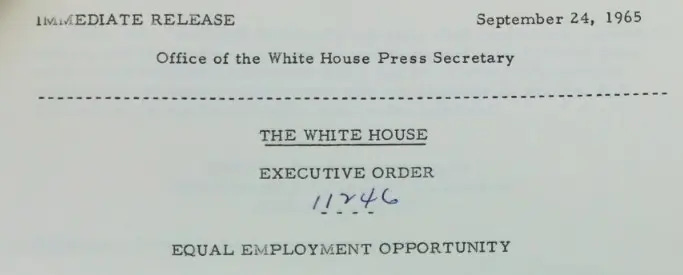

In covering a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, I visited the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin and saw the news release announcing the order:

In the order, Johnson — echoing Roosevelt nearly 25 years earlier — declared that it was “the policy of the Government of the United States to provide equal opportunity in Federal employment for all qualified persons, to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and to promote the full realization of equal employment opportunity through a positive, continuing program in each executive department and agency.”

This, Johnson declared, “applies to every aspect of Federal employment policy and practice.“

And so it stood, through the Nixon years, the Carter administration, the Reagan revolution, the Clinton era, sixteen years of Bush and Obama, a Trump administration, and the Biden years. There were amendments and additions, like then-president Barack Obama’s eventual addition of sexual orientation and gender identity to the order, but the order stood.

Until January 21, when Donald Trump revoked Executive Order 11246 after declaring that “[i]t is the policy of the United States to protect the civil rights of all Americans and to promote individual initiative, excellence, and hard work.“

In order to do that, Trump declared that the nearly 60-year old order needed to go.

That was Trump’s second day back in office.

A court blocks Trump’s effort to end birthright citizenship

On January 21, I wrote about the challenges to President Donald Trump’s executive order seeking to restrict birthright citizenship and a Thursday hearing in one of those cases.

At that hearing, U.S. District Judge John Coughenour, an 83-year-old Reagan appointee, issued a temporary restraining order blocking the order for the next two weeks while litigation — in his court and elsewhere — proceeds, as I covered in a note.

Reporters at the hearing in Seattle detailed that Coughenour strongly criticized the order as “blatantly unconstitutional” and harshly questioned the lawyers defending it.

Read more at my note:

This paragraph was corrected and clarified after publication, with the final edit at 12:45 p.m. Friday.

When I started as a new attorney in the Chicago regional office of the Solicitor of Labor, in 1979, I was handed a thick binder, with EO 11246 and related regulations. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance was the agency within USDOL that handled much of the enforcement of the executive order. Over the next 3O years I handled many matters related to the order (along with a lot of litigation in the myriad of other laws enforced by DOL).

Over the years, some administrations tried to cut back enforcement, but the program was never fully destroyed.

New administrations quickly learned that for all their grousing, many contractors liked the rules. They knew that integrated workforces were effective but this way they could blame the government for imposing the obligations.

Affirmative action is a touchy topic, but has a vital role in our society. This is a dark day.

Trump revokes …

Again, what is his alternative to DEI? Segregation? If so, say it out loud.