With Trump cases, the courts now must play their role in accountability

It is not anti-democratic to use the tools of our government to hold a person accountable for past anti-democratic actions.

The Supreme Court on Friday refused Special Counsel Jack Smith’s request to fast-track questions about whether Donald Trump can claim that presidential immunity bars his prosecution in federal court in D.C.

This, understandably, set off a flurry of responses — the second time this week that a court ruling appeared to directly affect the upcoming 2024 presidential election.

The first, obviously, was the Colorado Supreme Court ruling on Dec. 19 that Trump is disqualified from being president and cannot, therefore, appear on the state’s presidential primary ballot.

These are complicated questions, and those who stress that are right, but courts resolve complicated problems all the time. The number of people suddenly acting like courts can’t resolve novel or complex questions — and can’t do so without substantial time to do so — is embarrassing or disingenuous or both.

A serious underlying question here is about whether and how our nation responds to anti-democratic actions. Our system of government has set in place several tools for holding people accountable for such actions, and it is not anti-democratic to use them. It does not make them the only option for moving forward, but they are there for a reason.

The coming month — and likely months — will provide test after test for the Supreme Court on down as to whether our courts are willing and able to play their essential role in our system in a way that is forthright, timely, and allows for that accountability where it is being sought.

The courts can do this

First, as to Friday’s Supreme Court order, U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan earlier ruled that Trump cannot have his federal D.C. case dismissed on the presidential immunity ground, nor can his case be dismissed on the ground that “double jeopardy principles” prevent his prosecution for his actions related to Jan. 6, 2021, because the Senate failed to convict him in his second impeachment. Trump has appealed that decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Smith asked the justices to skip over that court and definitively resolve these questions, but the court, in a one-sentence order, said no.

Regardless of that, though, the D.C. Circuit was already set to hear arguments on the immunity and related questions on Jan. 9. That appeals court has provided quick rulings in these matters, and there’s no reason, given the expedited nature of this appeal, that they won’t do so here.

Some have expressed concern that Trump could then seek to delay the proceedings further. He could seek to do so, but the appeals court could take actions in association with a ruling to keep moving things forward more quickly. And the Supreme Court absolutely could still hear arguments in the case this term. If Chutkan’s ruling is affirmed by the D.C. Circuit, the justices could even again deny cert again if Trump appeals, ending the case. While possible, I do think it would be strange for the justices not to definitively resolve novel constitutional claims raised by a former president in relation to a prosecution of that former president. But, quick review of those questions could happen.

With the Colorado case, we are similarly facing a set of questions about what the justices will do and on what timeline they will do it. Trump has to seek Supreme Court review of the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision by Jan. 4. If he does so, the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling will remain stayed “until the receipt of any order or mandate from the [U.S.] Supreme Court.“

In other words, the Supreme Court could theoretically just moot out the case by not issuing an order before the primary. They could do that, but it would not moot the issue, because it would return — even in Colorado, for the general election, as well as potentially in other states. If the court does nothing to rule before the primary, it also could be seen, and rightly so, as effectively ruling on the issue without technically doing so (as the court did the night that Texas’s S.B. 8 abortion ban went into effect).

A lot of this is up in the air. The courts could, in effect, allow Trump’s obvious efforts to delay any criminal trials from taking place before the election to succeed. They similarly could avoid a ruling against Trump on the 14th Amendment matter on any number of grounds framed either as technical decisions or decisions attempting to “keep the courts out of it.”

With either set of issues, though, the courts can still address and answer the necessary questions in time to get all Trump-related cases resolved when needed.

I know this because I have watched for the past decade as state and federal courts do so — sometimes weekly or even twice a week — with people’s actual lives. Complex, novel legal issues are often resolved in death penalty cases before state supreme courts, federal district and appeals courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court in matters of days or even hours.

The U.S. Supreme Court — this court, in particular — has made it clear that it can resolve almost any capital case issue in whatever time it is given. They do so, even though the result — again, from this court, in particular — generally means that a person is dead within an hour or two of the high court’s decision.

And yet, when it comes to Trump’s criminal and constitutional woes today, a lot of people are writing a lot of words that can make it sound like they think it’s just all too complicated to resolve this quickly.

That’s bullshit.

And I think everyone will see that if they just stop for a minute and realize that courts regularly resolve literal life-and-death cases in hours sometimes.

“We know very well what this fight is about.”

I’m not denying the big picture, though. This is a difficult moment for the Supreme Court. I get that. (I would argue that much of that is of the court’s own making due to the way the Roberts court has frittered away its reputational capital in recent years, but, I’ll keep this to these issues for now.)

People on the left, middle, and center are fired up about one aspect of this or another — and they’re not wrong to be. In one instance, Steven Mazie and Stephen Vladeck urged in The New York Times on Saturday for an exercise of “the art of judicial statecraft” as part of their attempt to nudge the court to “somehow split[] the difference” in the cases:

I have to think (hope?) that the reason Mazie and Vladeck wrote this, even if they don’t say so directly, is because they don’t think the court will uphold the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling. So, they’re setting up a possible outcome that would at least keep the special counsel’s case moving forward on a quick-enough schedule.

If not that, I don’t get it. Why is this — interpretation of the post-Civil War amendments and application of one of those amendments’ provisions to a man who sought to ignore and overturn a presidential election — the time when a legal journalist and a law professor are urging the court to do something other than rule on important cases on their merits?

Sherrilyn Ifill, the former head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, has been talking about this issue on Threads. Although directly replying to a piece by Vox’s Ian Millhiser below, I think this response captures the essence of a lot of the smart arguments that she has been making:

I’m not sure what my liberal colleagues get out of behaving as though those of us who demand the application of the 14th amendment to Trump are naive or engaged in magical thinking. We know very well what this fight is about. And we know that no weapon in the fight against returning this authoritarian to the White House should be left on the table. Many of us are also the ones who will be at the forefront of protecting the votes of those most vulnerable to Trump’s targeting. Give it a rest.

Of course many people supporting the special counsel’s prosecution of Trump in D.C. or Fani Willis’s in Georgia or the 14th Amendment cases in Colorado or elsewhere are also going to be supporting political efforts to keep him out of office in the 2024 election. That there is such overlap, though, should in no way mean that accountability efforts for past actions should be ignored or discounted.

The levers of accountability

As I wrote on Friday, much of my thinking about these issues today comes out of the responses since Jan. 6, 2021.

When someone in society does something that people think is harmful to society, there generally are many possible ways of addressing it. When that harmful behavior is by the then-president in an attempt to overturn the election that would send him out of office, one would think that serious action to address it would be justified.

Several major efforts have been pursued to attempt to address Trump’s actions on Jan. 6. Four major levers have been pulled.

The first lever was Trump’s second impeachment. As we all know, Trump was impeached by the House but not convicted by the Senate in 2021 — a conviction that would have come with a bar on holding federal office.

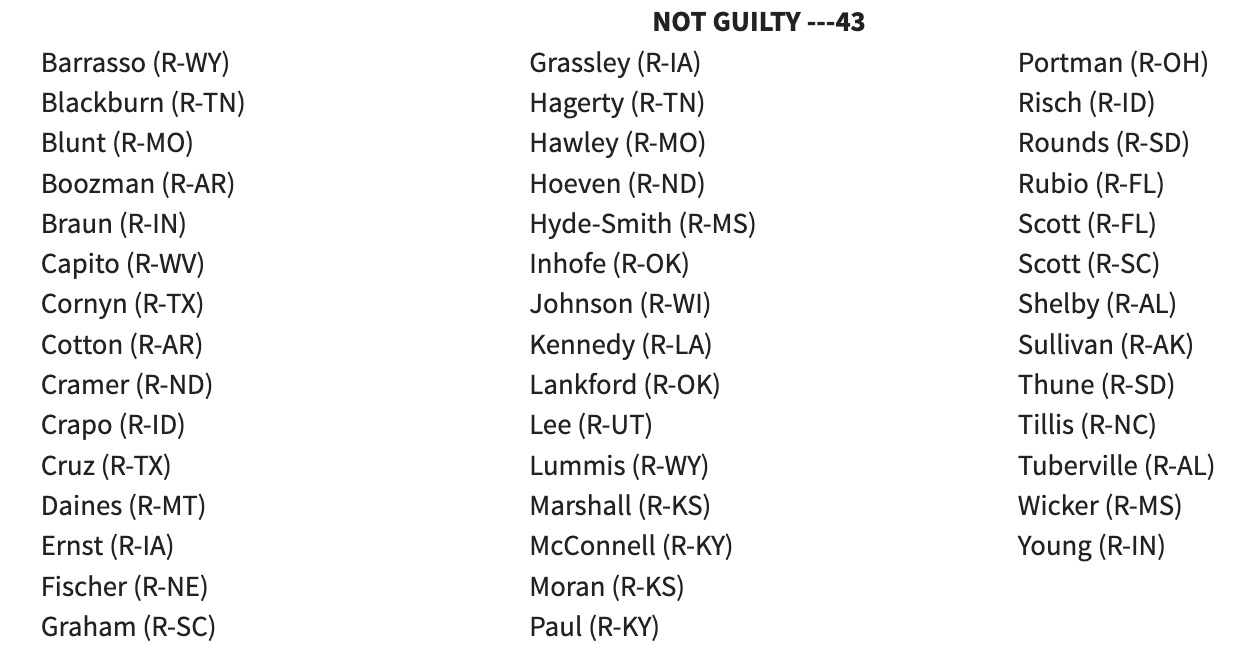

This was the most direct path to accountability, and I blame the U.S. Senate the most for the moment we are all in right now. Specifically, the 43 Republicans who voted not to convict Trump on Feb. 13, 2021. Any 10 of them could have ended this. They failed our nation that day.

Yes, as folks responded to me on Bluesky on Friday night, the House moved too slowly. Point noted. As I wrote there, though, I think criticism of “acting too slowly” is a difference of type, not degree, from criticism of “not acting.” And the Senate did not act.

In the Senate, only eight of those 43 “not guilty” votes on conviction had earlier voted to reject 2020 election results. Yes, that was eight too many, but, for these purposes my point is that 10 of those 35 — including Sen. Mitch McConnell — could have and should have ended this right there.

They didn’t, though, leading to other levers being pulled.

The next two levers were criminal investigations and a congressional investigation.

The Jan. 6 Committee — technically, the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol — released its final report on Dec. 22, 2022, after several public hearings, which had followed hundreds of interviews and review of countless documents.

The criminal investigations have led to multiple charges against Trump — currently in federal court in D.C. and in state court in Georgia.

The final lever is the 14th Amendment lever pulled most strongly thus far in Colorado.

I would have preferred a timeline in which the first lever did the heavy lifting (if that’s not mixing our metaphors). But, the Senate failed and here we are.

Given that, I don’t think any tools still available should be kept out of service to address such an egregious violation of our democratic principles. It is not anti-democratic to use the tools of our government to hold a person accountable for past anti-democratic actions.

And, yes, that includes going back to the ballot box, yet again, whenever necessary.

I, for one, am exhausted by the political and legal roller coaster that this country is on with no signs of an off ramp. Judge Luttig and Professor Tribe argue the 14th amendment should be upheld and to do so is not anti democratic, but indeed democratic, if I understand what these two legal scholars are saying. Unfortunately, even though Kavanaugh and Gorsuch have prior writings that would indicate they would uphold the 14th amendment in this case, don’t count on it. Remember their disingenuous reverence for precedence expressed in their nomination hearings that was dropped when confirmed? And, of course, Thomas should recuse himself as Ginni’s best friend, but that’s not happening either. So we slog on into 2024 terrified of what’s at the end of the ride.

agree about the Senate. It failed on the first impeachment too by too many saying "Oh, they proved their case of what he did, but I just don't think it is an impeachable offense. "

I'm of Team "thinks that the Extremes punted here because they know very well that the DC Circuit is going to get this in front of them right smartly." And that they will deny cert once the DC court has acted --and that's why there were no dissents on this denial. They can get the same result without having to endorse the rare prejudgment motion for cert.

The concept that ANY court could hold that presidents are simply immune no matter what they do is too scary to contemplate. Fingers crossed.