Texas said Brent Brewer was too dangerous to live. Thirty-two years later, they killed him.

A case over determining "future dangerousness." Update: Texas carried out the execution, after SCOTUS refused to stop it.

Brent Brewer was convicted of killing a man in 1990 when he was 19 years old and in the midst of an ongoing mental health crisis. Thursday night, Texas plans to kill Brent Brewer for that crime.

Texas said capital punishment was necessary, essentially, because Brewer was too dangerous to let live. They used the testimony of a man who Brewer’s lawyers described as “the most discredited and notorious forensic expert in the state of Texas” to get the jury to make this finding of “future dangerousness.“

That was, initially, in 1991, although the first conviction was tossed out and he was re-tried in 2009 with similar evidence — including the same witness, Richard Coons.

Based on Brewer’s behavior since, it would seem — on its face — that that assessment and those claims were wrong.

And yet, Texas is going forward with seeking to kill him on Thursday.

Brewer’s execution would be the 21st in the U.S. this year and the seventh in Texas in 2023.

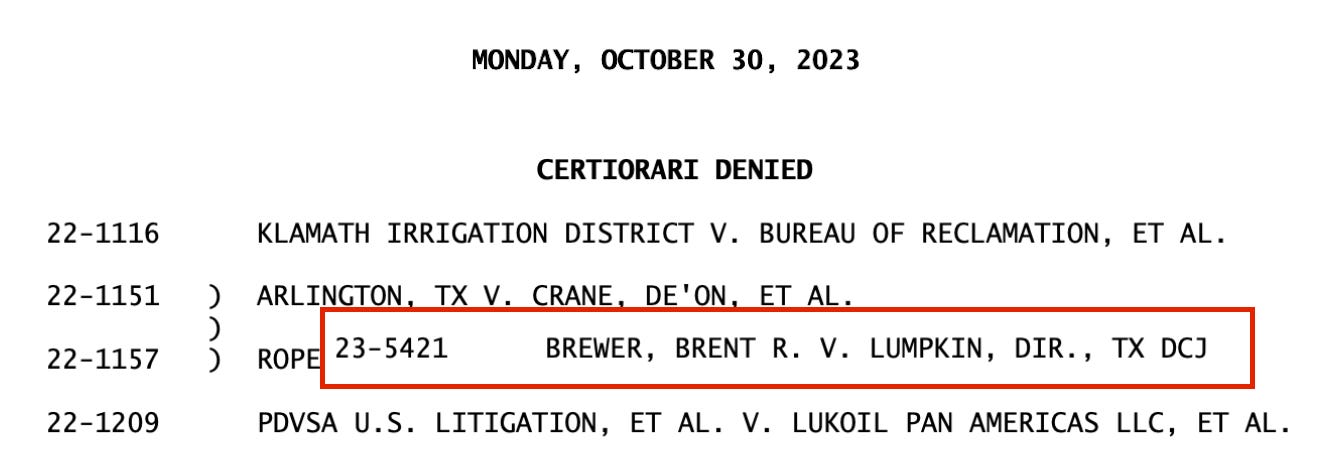

The Supreme Court already denied his primary appeal in his case — a petition for a writ of certiorari — on Oct. 30. A petition for rehearing and request for a stay of execution are pending, but more on that after we go through what’s going on.

[Update, 5:15 p.m.: The Supreme Court rejected Brewer's requests, allowing Texas's execution to proceed Thursday night. There were no noted dissents.

The Supreme Court, again, gave no explanation for its decision.]

[Update, 9:30 p.m.: Texas killed Brent Brewer, the Texas Tribune reported.]

At Balls & Strikes, Jay Willis wrote about Brewer’s initial request, how Texas sought to prove (and I use that term loosely) Brewer’s “future dangerousness” to justify sentencing him to death, and the broader issue of “future dangerousness”:

As Willis wrote about “future dangerousness” claims:

As early as 1983, the American Psychiatric Association told the Supreme Court that “the unreliability of psychiatric predictions of long-term future dangerousness is by now an established fact within the profession,” and that at least two of three expert predictions of future dangerousness turned out to be flat-out wrong. A study of 155 people on Texas’s death row found eight who’d committed disciplinary infractions in prison that required the provision of treatment beyond first aid; 31 of them had no infractions at all. A 2005 review of available research concluded that clinical assertions about propensity for violence are “highly inaccurate and ethically questionable at best.”

The legal issue resulting from testimony about “future dangerousness” in Brewer’s case is technical, but important: It is, as Willis wrote, “under what circumstances federal courts must grant ‘certificates of appealability,’ which allow people in [Brewer’s] circumstances to challenge denials of post-conviction relief.” The general standard is that a certificate of appealability is to be granted when the issue is “debatable among jurists of reason.”

In Brewer’s case, a judge on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals would have granted relief and the state and federal courts reached “conflicting decisions … in resolving the same claim,” so, his lawyers argued, this is obviously a case where the issue is “debatable among jurists of reason.”

The Supreme Court nonetheless rejected the petition on Oct. 30, giving no reason for its denial — and with none of the justices even noting their dissent.

This is becoming the new normal at this Supreme Court. There are six justices — the Republican appointees — unlikely to grant relief in all but the most extreme capital cases (or in some cases involving certain religious claims). It appears that the remaining three justices — the Democratic appointees — have moved toward not objecting as often so as to be able to make a point when they do so, as they did in Jedidiah Murphy’s case last month.

This is not, however, the end of Brewer’s case. On Tuesday, Brewer’s lawyers filed a petition for rehearing — asking the court to take a second look at his petition, primarily due to the fact that the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles had recommended against granting Brewer’s clemency petition. The petition also presents more evidence of a split by courts below about the “certificate of appealability” question. Along with that, as is the norm when an execution date is pending, Brewer’s lawyers also filed a request for a stay of execution while the court considers his rehearing petition.

This is a last-ditch effort, to be clear, and almost certainly won’t succeed.

But, if the Supreme Court is going to allow executions to proceed when legitimate legal claims are raised and not resolved, lawyers absolutely should keep pressing the justices to actually explain why. Here, that means seeking relief or an explanation why — if they again deny his requests — they are letting Brent Brewer be killed tonight.

I guess the only time you are not too dangerous for the conservatives on this Supreme Court is when you have engaged in domestic violence. Then you get an assault rifle and your freedom.

Yes, I do know there’s been a conviction here, but their convenient oversight of the questionable nature of the conviction really cuts the other way. We all know how many judges are former prosecutors or even if not, pretty much rubber stamp whatever they request (unless you are Aileen Cannon overseeing a Trump case). For a conviction to be overturned in Texas - well, a reasonable lawyer can see that forest through the trees.

So another dead prisoner , yee-haw Texas. Depressing.

I respect the liberal justices enough to think they have somehow reasonably convinced themselves that not saying anything (even when they dissent publicly, and that is fairly rare, repeatedly it is without comment) helps in the long run.

I don't know exactly why. I question the value of it. But, I'm not there.

Sotomayor previously managed to drop a few more statements in death penalty cases. If the conservatives are so touchy that the two more outspoken liberals (Jackson more outspoken than Breyer so far) can't drop a statement of concern or even dissent in a death penalty case without them using it to change the law or something to the worse (in a liberal's view), it's kind of stinks.

But, I guess we sort of know that. Still, I'll repeat , granting it's not my call, it's to me a bad policy. This is not a trivial case. Sometimes, these last shot cases are. The death penalty might always be bad; not all last minute appeals have much going for them.

I think it would be appropriate always to have at least a brief statement when a life is involved. But, in a case like this, it should be truly provided. I have been told Chris Geidner generally agrees. So, just stating my mantra here. I think it matters.