Federal judge rules Tennessee drag restrictions unconstitutional after trial

The anti-drag law lost on all fronts. "[L]aws infringing on the Freedom of Speech must be narrow and well-defined." This law "is neither," the Trump appointee ruled.

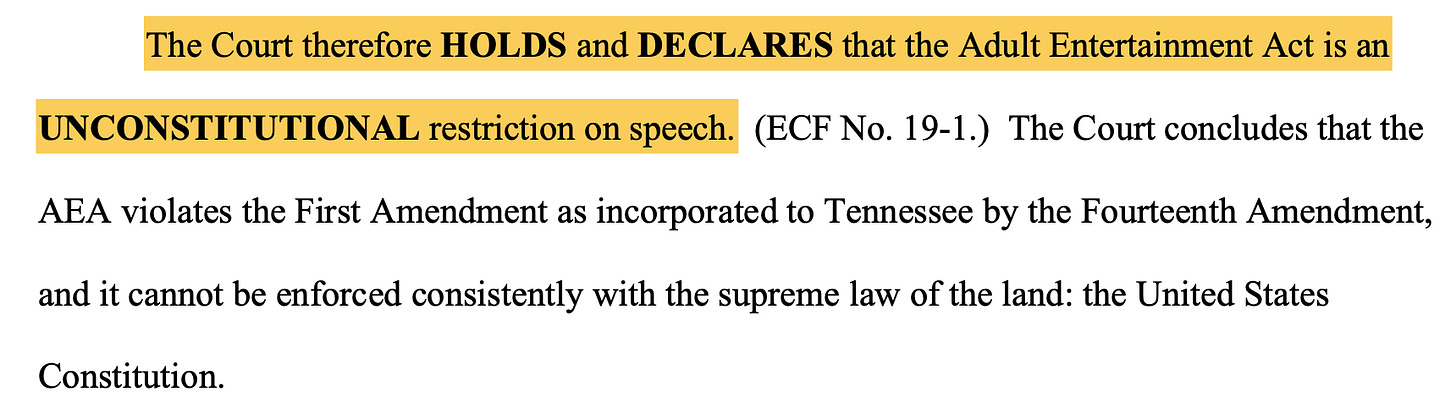

A federal judge appointed by Donald Trump ruled late Friday night that Tennessee’s Adult Entertainment Act (AEA), which would restrict drag performances in the state and threaten performers who violate the law with felony criminal penalties, is unconstitutional.

“The Tennessee General Assembly can certainly use its mandate to pass laws that their communities demand,” U.S. District Judge Thomas Parker wrote. “But that mandate as to speech is limited by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which commands that laws infringing on the Freedom of Speech must be narrow and well-defined. The AEA is neither.”

Parker, appointed to the bench in 2017, found after a two-day trial that the law — criminalizing “adult cabaret entertainment” performances anywhere “where the adult cabaret entertainment could be viewed by a person who is not an adult” — is unconstitutional on several grounds.

Parker did not shy away from the underlying issues, either.

“The word ‘drag’ never appears in the text of the AEA,” Parker wrote. “But the Court cannot escape that ‘drag’ was the one common thread in all three specific examples of conduct that was considered ‘harmful to minors,’ in the legislative transcript.”

After detailing that legislative history, as shown in four transcripts reviewed by the court, Parker found that “the legislative transcript strongly suggests that the AEA was passed for an impermissible purpose.”

That “impermissible purpose,” Parker found, was “chilling constitutionally-protected speech.”

In describing the concerns surrounding potential enforcement of the law, Parker seemed particularly well-attuned to the fears expressed by the plaintiffs in the case and others, writing, “The chance that an officer could abuse th[e] wide discretion [given for enforcing obscenity laws] is troubling given an art form like drag that some would say purposefully challenges the limits of society’s accepted norms.”

In a particularly striking portion of his decision — finding that the law was “substantially overbroad” and could therefore be struck down in whole — Parker analogized the remedy to “strong medicine.”

He went on:

But a debilitated patient should not forgo medicine on account of its strength. This statute—which is barely two pages long—reeks with constitutional maladies of vagueness and overbreadth fatal to statutes that regulate First Amendment rights. The virulence of the AEA’s overbreadth chills a large amount of speech, and calls for this strong medicine.

Parker had previously blocked Tennessee from enforcing the law, passed earlier this year as S.B. 3, hours before it was to go into effect. The May 22-23 trial followed.

In depth

After finding that Friends of George’s — the performance group that sued, which produces “drag-centric performances, comedy sketches, and plays” — had organizational standing to bring the lawsuit, Parker ruled that the law failed, as a constitutional matter, on all fronts.

Because the law, Parked found, sets forth both content-based and viewpoint-based restrictions and was passed with an impermissible purpose of chilling protected speech, strict scrutiny — the test that renders a law “presumptively unconstitutional” — applies. Parker went on to find that the law failed strict scrutiny and then also found that the law violated two other constitutional restrictions, ruling that it fails because it is both too vague and, as noted above, overbroad.

As summarized by Parker:

Parker, went through each of those First Amendment and related rules and explained why the law fails. Suffice it to say, losing on every front is not good if you’re the Tennessee Attorney General’s Office, which represented Shelby County District Attorney General Steven Mulroy in his official capacity, defending this law.

Beyond that constitutional framework, though, Parker’s decision also came down to some pretty clear structural problems that Parker saw with the law — and questions about discrimination that Parker clearly saw at issue in the law and its passage.

Parker highlighted that the AEA was different from other Tennessee laws in a way that raised significant First Amendment expressive conduct concerns.

“The bill criminalizes, or at least chills, the expression of a class of performers, rather than the business operators, or even parents, who facilitate the exposure of adult cabaret entertainment to minors,” he wrote. Past laws focused on businesses. This law focused on performers. That, to him, was a pretty big flashing sign that this law was no good.

Additionally, key to Parker’s legal analysis were three other aspects of the Tennessee law that he believed threw its constitutionality into doubt.

Parker repeatedly raised the fact that there was no “scienter” requirement in the law — a legal reference to the state of mind required to find a person guilty of committing a specific crime, such as “knowingly.” At one point, he wrote, “[T]he AEA’s lack of a textual scienter requirement troubles the Court for a statute that regulates speech with criminal sanctions.”

In the absence of that scienter requirement, he was very concerned that the law also contained no affirmative defenses that those charged could raise against the law, including — as he noted was present in other laws addressing children’s access to adult material — parental consent. ”Nothing in the legislative history indicated the legislators even contemplated adding these narrowing mechanisms to their statute that criminalized forms of expressive speech,” Parker wrote.

The geographic coverage of the law was a key part of Parker’s concern. “[T]he Court finds that the AEA regulates an area that is of an alarming breadth,” he wrote, suggesting that, because children “could be” anywhere, the law’s restrictions could apply anywhere.

Finally, and multiple times throughout the opinion, Parker — again, a Trump appointee — was willing to address, fairly directly, how he saw discrimination at play in the law’s passage and effects.

“[W]hile including ‘male or female impersonators,’ in a list with ‘topless dancers, go-go dancers, exotic dancers, strippers . . . or similar entertainers’ may have escaped many readers’ scrutiny in 1987, it may not do so with ease in 2023,” Parker wrote, detailing legal and political changes experienced by LGBTQ people in the intervening years. “This Court views categorizing ‘male or female impersonators’ as ‘similar entertainers’ in ‘adult-oriented businesses’ with skepticism.”

After explaining that skepticism in detail, Parker concluded, “Given an appropriate scope, [Tennessee] may regulate adult-oriented performers who are harmful to minors. But it cannot, in the name of protecting children, use the AEA to target speakers for a reason that is unrelated to protecting children.”

That, Parker found, is exactly what happened here.

“The Court finds that the AEA’s text targets the viewpoint of gender identity —particularly those who wish to impersonate a gender that is different from the one with which they are born,” he wrote.

The effect of the ruling was not immediately clear. Enforcement is only enjoined as to Mulroy and Shelby County, but the court also declared the law to be unconstitutional — and the Tennessee attorney general’s office represented Mulroy in this case.

This is a developing story. More to come at Law Dork in the coming days.

This is fantastic news to wake up to!

Great to wake up to some good news!