Supreme Court's conservatives give "defund" Planned Parenthood efforts a win

The legal issue: A sharp dispute over the civil rights law that formed the basis for the group's lawsuit against South Carolina when the state barred it as a Medicaid provider.

On Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservatives blocked Medicaid recipients from suing South Carolina over its decision to reject Planned Parenthood as a covered Medicaid provider.

The 6-3 decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic is a significant win for the anti-abortion effort to “defund” Planned Parenthood — a reality seen in the fact that the far-right Alliance Defending Freedom represented South Carolina before the Supreme Court. At arguments, the ADF lawyer representing the state admitted freely that Planned Parenthood’s abortion services were the reason why South Carolina rejected Planned Parenthood as a Medicaid provider.

Despite the abortion context and significance of this decision coming in the aftermath of the court having overturned Roe v. Wade, the legal dispute before the justices was over private enforcement of a Reconstruction-era civil rights law, the Civil Rights Act of 1871.

What’s more, the three opinions in the case suggested a fraught path ahead for Section 1983, the provision of the civil rights law that allows individual lawsuits when a person has faced “deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws” by a state actor.

First, the Medicaid case.

Lower courts had found repeatedly that individual lawsuits were allowed under Section 1983 for claimed violations of what is known as the “any qualified provider” provision in the Medicaid law. On Thursday, though, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the six-justice majority that the “any qualified provider” provision did not include “clear and unambiguous rights-creating language” that would justify the court holding that it is the sort of “atypical case” where a Section 1983 lawsuit is allowed.

Gorsuch wrote for the court that the language in the “any qualified provider” provision “looks nothing like” a provision in the Federal Nursing Home Reform Act that the court held recently does authorize Section 1983 suits.

Quoting the FNHRA language, which included the word “right” or “rights” multiple times, Gorsuch then wrote, “Congress knows how to give a grantee clear and unambiguous notice that, if it accepts federal funds, it may face private suits asserting an individual right to choose a medical provider.“ The “any qualified provider” provision, he continued “could not have been more different.“

In dissent, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, wrote that “[t]he majority’s hyperfocus on FNHRA” as — quoting Gorsuch — “the only reliable yardstick against which to measure whether spending-power legislation confers a privately enforceable right“ under Section 1983 “widens the gap“ between the test the court uses to allow for Section 1983 litigation and “the text of Section 1983 itself.“

Because of that, she wrote, “the Court adopts an approach to §1983 that not only undermines the statute’s core function but also stretches our doctrine beyond anything that can be justified as a matter of text, precedent, or first principles.”

As to Thursday’s case, she continued, “Medicaid’s free-choice-of-provider provision easily satisfies the unambiguous-conferral test,“ noting that “the text of the provision is plainly phrased in terms of the persons benefited—namely, Medicaid recipients.“

But, on Thursday, Gorsuch — with support from all of the Republican appointees — held otherwise, further constricting the availability of Section 1983 lawsuits and providing another win to anti-abortion forces.

But, there was more.

Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with Gorsuch’s opinion for the court, but wrote a separate concurring opinion to — as he often does — explain how the court could go even further.

“In appropriate cases,” Thomas wrote, “we should reassess §1983’s bounds, including its application in the spending context and our understanding of the ‘rights’ enforceable under §1983.“ This reassessment, he posited, is needed because “[t]he history of §1983 makes clear that the statute has exceeded its original limits.“

Addressing the history of the provision, he noted that the provision did not come into use often in the immediate aftermath of its passage — citing a source providing that there were “only 21” Section 1983 cases decided in the law’s “first 50 years.” Further, he wrote, “When courts did face §1983 cases, they construed the statute narrowly.“ The court’s interpretation, he continued, “took a sharp turn“ in the 1960s, resulting in a “broaden[ed]” interpretation — and use — of Section 1983. “The upshot of these decisions was that §1983 can reach ‘any and all violations’ of rights secured by the Constitution or federal law.“

Then, he struck: “The ‘scant resemblance’ between §1983 today and §1983 as it was traditionally understood creates good reason to doubt our modern understanding.“ He urged the court to act. First, Thomas wants no Section 1983 lawsuits to be allowed under Spending Clause legislation: “[I]n a case where the issue is properly presented, I would make clear that spending conditions—which are by definition conditional—cannot ‘secure’ rights.“ Second, he wants the “rights” able to be protected through lawsuits under Section 1983 to be dramatically scaled back: “We should revisit the threshold question of what constitutes a ‘right’ under §1983.“ Specifically, he added, “the answer to that question turns on how ordinary readers would have understood the phrase ‘rights, privileges, or immunities’ in 1871.“

In short, if the majority on Thursday curtailed Section 1983’s availability, Thomas wants to see it eviscerated.

Despite it being a solo concurrence, Jackson was not going to leave it out there unanswered.

Noting Thomas’s call for a “fundamental reexamination” of Section 1983 litigation, she wrote, “Because his opinion is not tethered to the specific facts or arguments presented in this case, an extensive response is not necessary here. But it is worth pausing briefly to think about whether the historical account he offers reflects the level of depth, nuance, or context needed to support the wholesale reappraisal he is envisioning.“

The comment reflects a growing unwillingness from Jackson to give Thomas — or anyone on the court — room to spitball without facts supporting their claims. For example, regarding Thomas’s comment about the few early cases invoking Section 1983, Jackson also responded with history. “[F]iling civil rights lawsuits during the Jim Crow era could be quite perilous, especially for the people whom the statute was originally meant to benefit,” Jackson wrote. “Many would-be plaintiffs had reason to fear that filing a lawsuit would lead to physical or economic reprisals. Add to that the difficulty of finding a lawyer, prevailing before often-hostile juries, and (if successful) enforcing a judgment, and it is not hard to imagine that the dearth of §1983 lawsuits in the wake of Reconstruction might have myriad alternative explanations.”

In short, she concluded regarding Thomas’s free-standing concurrence, “more caution (and more research) may be warranted before our longstanding precedents in this area can be seriously scrutinized or attacked—especially in cases where no party has made such a claim or presented any such argument.“

Law Dork out and about

As we learned Thursday morning, the final decisions of the term are all coming Friday, so I’ll be back at the Supreme Court tomorrow.

But, first, I'll be on Alliance for Justice's virtual SCOTUS Term Review panel at 3 p.m. Thursday (today). Sign up here or watch live here.

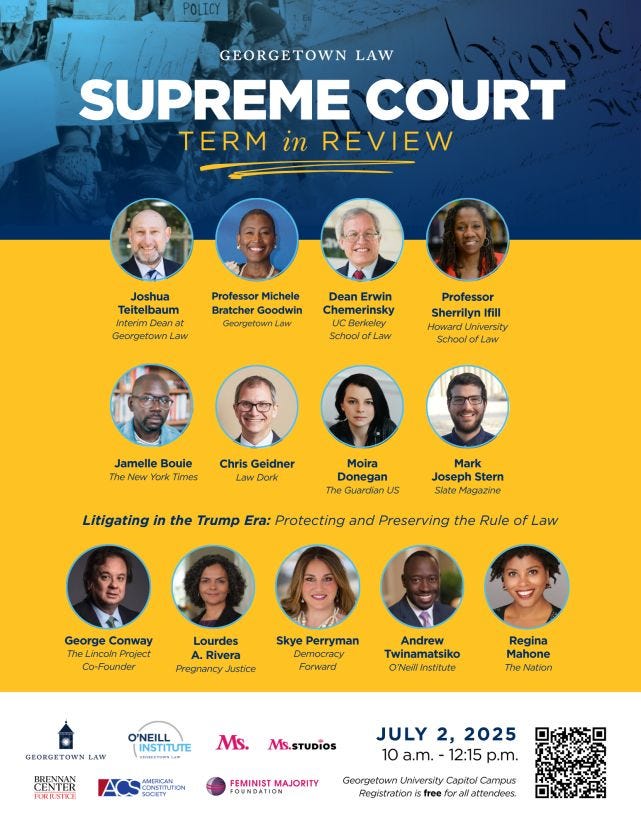

Then, next week, on July 2, I'll be at Georgetown Law's SCOTUS Term in Review.

Sign up for that here. (I believe the Georgetown Law event will also be shown on C-SPAN.)

Justice Jackson: Let no dicta go unchallenged. Thomas pulls this stuff often enough, in fact emboldening the ineffable Judge Aileen Cannon to dismiss the Mar-a-Lago docs indictment based upon Thomas' remarks in his concurring opinion in re: *tRump v United State* immunity case.

Justice Jackson is fighting the good fight, "collegiality" notwithstanding.

These idiots don’t realize PP provides medical care for men too. Not everything is about abortion.