Supreme Court, on a 6-3 vote, blocks Trump's IEEPA tariffs

Chief Justice John Roberts found that there actually are structural limits on the president's powers.

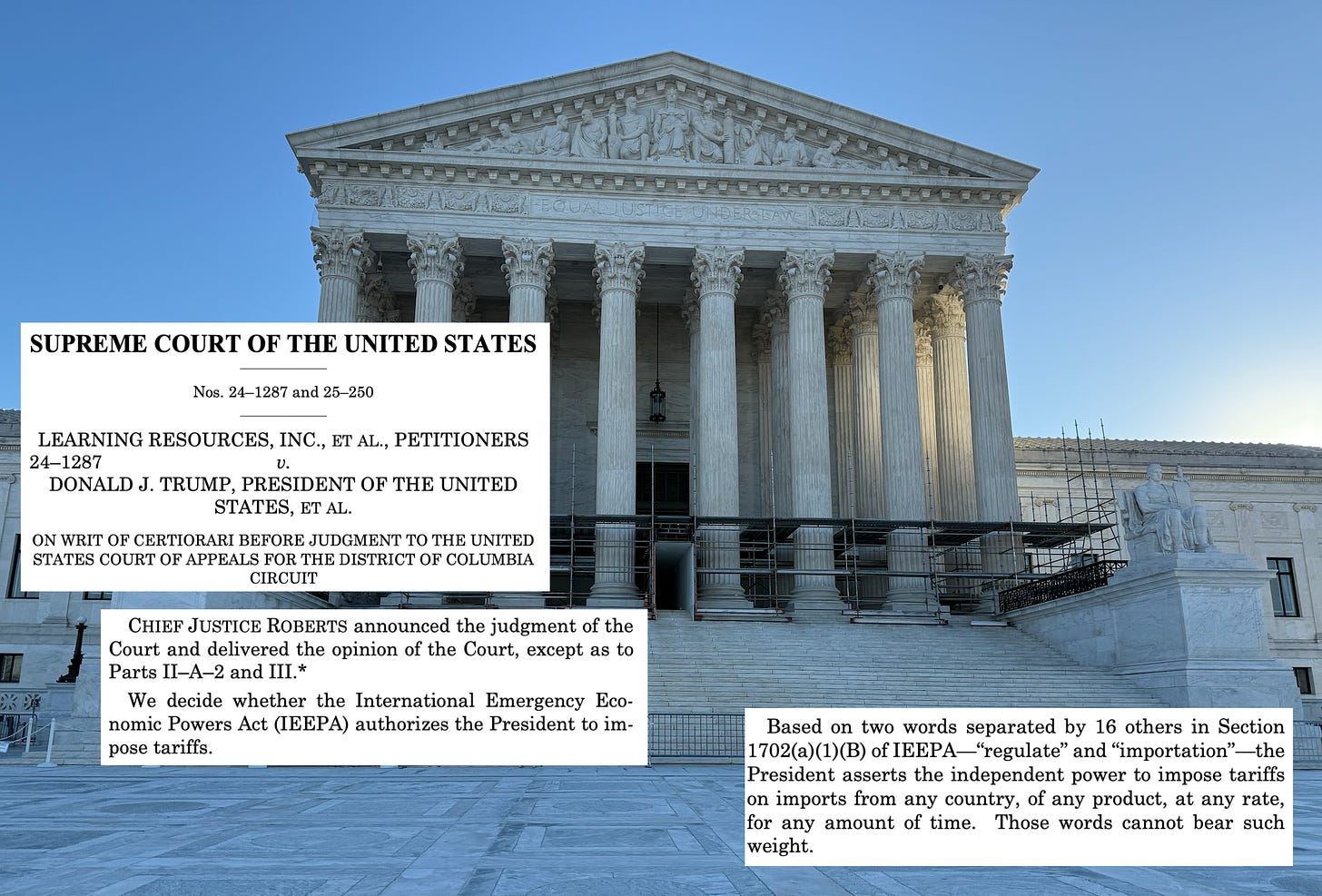

The U.S. Supreme Court on Friday struck a blow to one of President Donald Trump’s key economic policies, holding on a 6-3 vote that Trump’s the challenged set of Trump’s mass-tariffs are not authorized by the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA).

“When Congress grants the power to impose tariffs, it does so clearly and with careful constraints. It did neither here,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the court.

“Based on two words separated by 16 others in Section 1702(a)(1)(B) of IEEPA—’regulate’ and ‘importation’—the President asserts the independent power to impose tariffs on imports from any country, of any product, at any rate, for any amount of time. Those words cannot bear such weight,” Roberts wrote.

It is a remarkable document showing that Roberts — and a majority of the court — do, in fact, know how to do law. They do understand our constitutional structure and presidential limits — at least when the economic system is at issue.

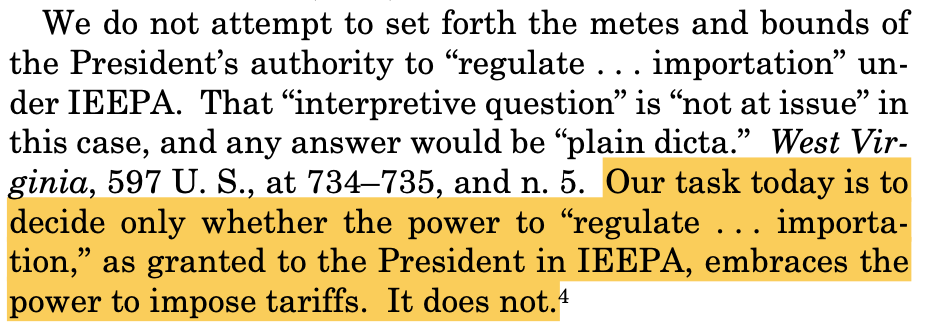

“Our task today is to decide only whether the power to ‘regulate . . . importation,’ as granted to the President in IEEPA, embraces the power to impose tariffs,” Roberts wrote. “It does not.”

The result was not a surprise following the November oral arguments in the case.

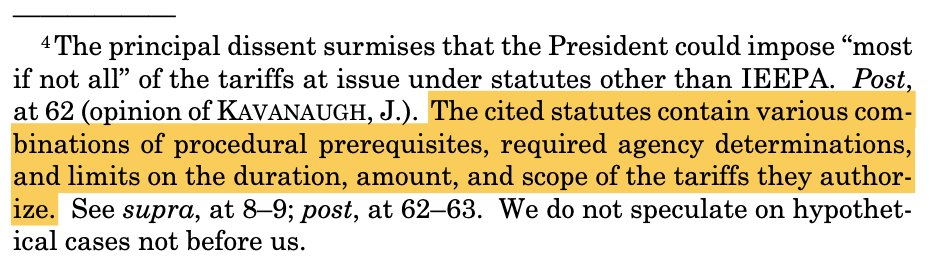

In a section of his opinion that was only written for himself and Justices Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, Roberts raised the recent pedigree of the “‘major questions’ cases” as providing support for the ruling.

Invoking “the core congressional power of the purse“ — a change from a few months back — Roberts wrote that “if Congress were to relinquish that weapon to another branch, a ‘reasonable interpreter’ would expect it to do so ‘clearly.’ … When Congress has delegated its tariff powers, it has done so in explicit terms, and subject to strict limits.” Noting the economic impact of these tariffs, moreover, Roberts wrote, “These stakes dwarf those of other major questions cases.”

In sum, Roberts wrote for the trio, [T]he President must ‘point to clear congressional authorization’ to justify his extraordinary assertion of the power to impose tariffs. … He cannot.”

There were 170 pages of opinions — although most of those pages came from Gorsuch’s opinion concurring with Roberts’s opinion for the court and Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s dissent written for himself and Justices Clarence Thomas and Sam Alito.

Roberts explained what the court was not deciding — both as to other uses of IEEPA and as to other tariff authorities.

Gorsuch and Barrett both wrote concurring opinions, primarily disputing what the “major questions doctrine” is and how it is to be used.

Gorsuch, essentially thinks virtually everyone else is wrong, hypocritical, or both. He, virtually alone, is pure. He explained:

This went on for 46 pages.

Barrett responded in 4 pages, noting in key part:

To the extent that JUSTICE GORSUCH attacks the view that “common sense” alone can explain all our major questions decisions, ante, at 18–22, he takes down a straw man. I have never espoused that view. Rather, as I explained in my concurrence in Biden v. Nebraska, 600 U. S. 477, 507 (2023), the major questions doctrine “situates text in context” and is therefore best understood as an ordinary application of textualism.

Justice Elena Kagan wrote an opinion concurring in part and concurring in the court’s judgment, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson — who also wrote her own partial concurrence.

Kagan argued, in essence, that this is a normal statutory interpretation case and the “so-called major-questions doctrine” — as she put it — need not be a part of this case at all:

As she later detailed, “[S]traight-up statutory construction resolves this case for me; I need no major-questions thumb on the interpretive scales.“

For her part, Jackson used Friday’s decision as another opportunity to push legislative history back onto the Supreme Court stage.

Jackson described the major questions doctrine as “a framing that asks, in essence, whether Congress ‘would likely have intended’ to delegate the authority to tariff to the President through IEEPA.” To that, Jackson wrote:

While probing Congress’s intent is the right inquiry, my colleagues speculate needlessly. In my view, the Court can, and should, consult a statute’s legislative history to determine what Congress actually intended the statute to do.

This is, she explained, key to her understanding of the judicial role.

“When Congress tells us why it has included certain language in a statute, the limited role of the courts in our democratic system of government—as interpreters, not lawmakers—demands that we give effect to the will of the people,” Jackson concluded.

In Kavanaugh’s dissent for himself, Thomas, and Alito, he addressed the broad authority claimed by stating that “IEEPA merely allows the President to impose tariffs somewhat more efficiently to deal with foreign threats during national emergencies.”

As to the major questions doctrine, in a key portion of his dissent, Kavanaugh claims a foreign affairs exception applies to the already questionable “doctrine.” He wrote:

Along with Kavanuagh’s 63-page dissent for the trio, Thomas also, unsurprisingly, wrote a solo dissent.

As he often does, Thomas explained that he has a different view of the Constitution. On Friday, it was a nondelegation doctrine exception that would allow certain wholesale delegations.

But, on Friday, Thomas was alone on that front.

Nowadays, 6 to 3 is practically unanimous.

Good.

What difference will this make? How will it be used? Are there going to be suits for reimbursements on lost income? So many questions. Gorsuch is more of a pompous ass than even *I* thought.