Donald, death, and immunity

Donald Trump likes the death penalty, and he wants to be president again — with the immunity decision to back him. Also: A deadly wellness check. And: Closing my tabs.

The past week has shown us that the death penalty can and will be carried out, even in questionable circumstances, when an executive wishes to do so — and the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservatives will not stop it.

That’s important to think about as Donald Trump fights to get back in the White House.

There are 40 people currently on the federal death row currently, according to the Death Penalty Information Center,1 and Trump, if re-elected, almost certainly will resume federal executions like the death spree his Justice Department oversaw in his first term.2

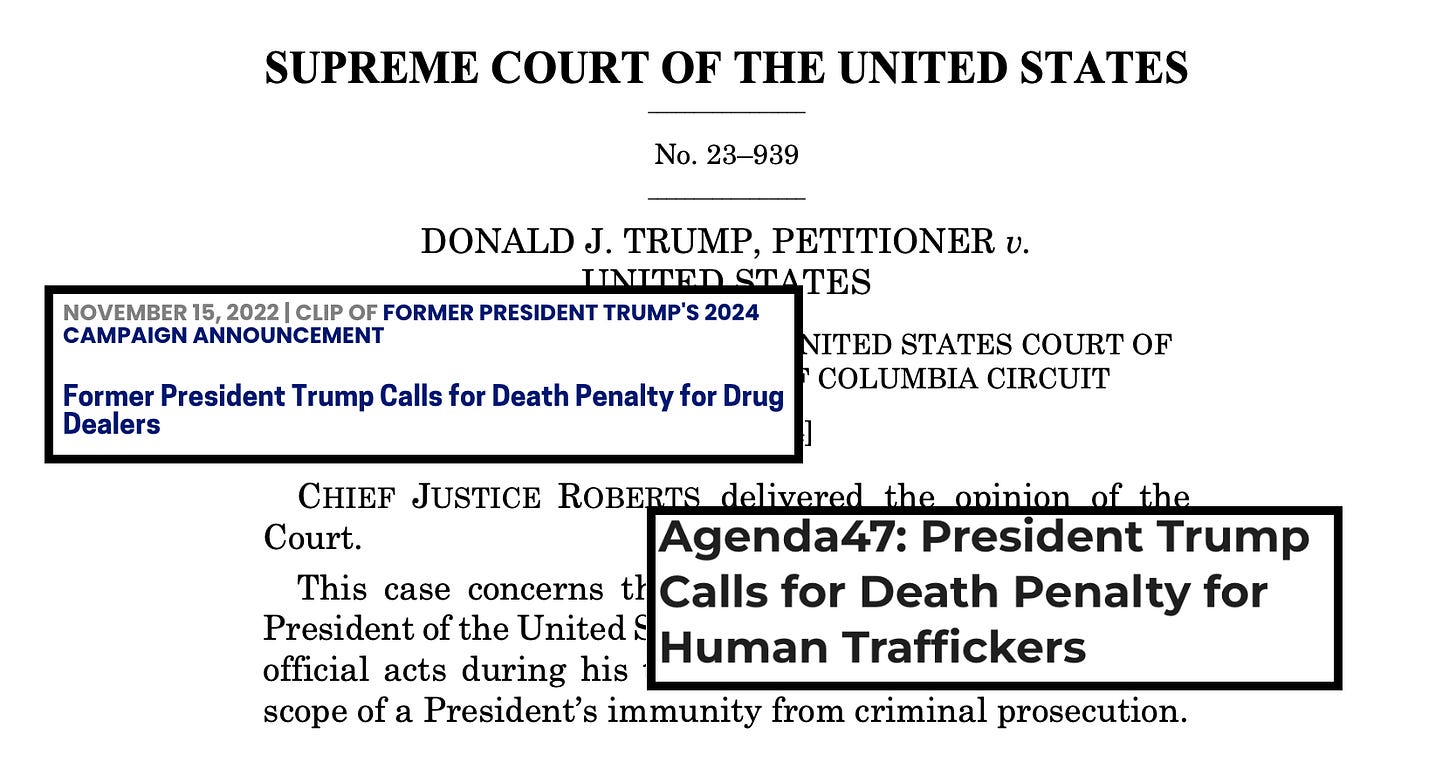

What’s more, Trump has repeatedly called for expanding the federal death penalty.

“I will urge Congress to ensure that anyone caught trafficking children across our border receives the death penalty immediately,” President Trump said last year.

And, drug dealers. And, quickly, for those who kill police officers. (His aims haven’t always been limited to congressionally-backed plans, former staffers have stated.)3

This is the sort of robust exercise of executive power that Chief Justice John Roberts has said must be protected in Trump v. U.S.

In that decision, Roberts wrote that “the President must therefore be immune from prosecution for an official act unless the Government can show that applying a criminal prohibition to that act would pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.’”

Under that standard for overcoming the presumption of immunity for actions within the “outer perimeter” of a president’s official acts, it is hard to imagine this court viewing carrying out an execution — authorized under whatever limited process has been determined people are due — as ever being prosecutable.

What’s more, if Trump could argue that an execution was carried out in exercise of any of his “core” constitutional powers, then no one could stop him.

“[A]n Act of Congress—either a specific one targeted at the President or a generally applicable one—may not criminalize the President’s actions within his exclusive constitutional power,” Roberts explained. “Neither may the courts adjudicate a criminal prosecution that examines such Presidential actions.”

Sure, that’s not the sort of scenario we expect to have to deal with, but that’s also not outside the realm of possibility in a second Trump administration. (And how many scenarios did we not expect to have to deal with before Trump’s first election that very much came to pass?)

And yet, that’s the sort of unintended (intended?) consequence of the Trump immunity decision. The possibilities for holding presidents accountable under the criminal law, even when not written off altogether, were put into serious doubt by Roberts’s decision — a decision that supercharged the presidency as Trump’s effort to retake the office was well underway.

The death penalty — and exercise of authority related to it — likely only will be one of many issues that would arise were Trump to regain power, but it is a particularly stark one that deserves attention.

“A tragically common example“

On Friday, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit unanimously held that members of the Young County, Texas, sheriff’s department were protected by qualified immunity from a lawsuit filed after a deputy shot a man dead as a result of a call for a wellness check in June 2021.

In spite of any questions that this decision itself raises — and it does — it is notable to me how damning an assessment of our entire social care system it provides.

In this case, the family of Steve Winder, a man with a gun and a history of depression, sought a wellness check for him. The arriving deputy fatally shot Winder within 28 seconds of arriving on scene.

“Suicidality presents a tragically common example of exigent circumstances“ overcoming the need for a warrant under the Fourth Amendment, the per curiam — unsigned — decision from Judges Edith Jones, Don Willett, and Kurt Englehardt declared.

It was the sentence that followed, though, that tells the tale.

See, e.g., Rice, 770 F.3d at 1131 (granting qualified immunity) (“This is not the first time we have encountered a tragic factual scenario like the one present here: a police officer, in an attempt to aid a potentially suicidal individual, entered without a warrant and killed the person the officer was trying to help.”) (collecting cases).

“Collecting cases.”

That was a 2014 case. “Collecting” still earlier cases. This has been happening — and keeps happening.

Friday’s ruling all but says that this will continue happening.

As for Winder’s case, there were questions. “Much confusion exists around whether Steve was, in fact, holding a gun the moment he was shot,” the unsigned opinion stated. Nonetheless, the court continued, no matter. “[W]hether Steve was in fact aiming a gun at Deputy Gallardo does not matter,” the court stated. “[B]inding caselaw demonstrates that what matters is whether Deputy Gallardo could reasonably believe that Steve was reaching for or had a gun.”

Courts created qualified immunity, and this is — as of now — result.

More broadly, the panel quickly rejected the call from the man’s family to “upend” the doctrine of qualified immunity:

While that is the correct role of an intermediate court, I would like to note the irony of a Fifth Circuit panel of all Republican appointees strongly defending the limits of their role and their need to respect precedent. (See, e.g., Law Dork.)

Closing my tabs

This Sunday, here are the tabs I’m closing: