This week, we faced all that the Dobbs justices unleashed

From reproductive rights to marriage equality to trans lives, the fallout from the decision overruling Roe v. Wade is extreme, dangerous — and expanding.

The five justices of the U.S. Supreme Court who overturned Roe v. Wade 20 months ago Saturday gave a green light to a new brand of Republican extremism in hyperdrive — a hyperdrive that has been on full, frightening display this week.

Many of the most extreme legal developments since late 2020 have been advanced by far-right Christian legal advocates or authoritarian Trump backers. In turn, the Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and other rulings since then have empowered those advocates to go further.

Three of the biggest stories in the news this week are, more or less directly, the result of Justice Sam Alito’s Dobbs opinion for the court — joined as it was by Justice Clarence Thomas and Donald Trump’s three appointees, Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Mix in Gorsuch’s 2023 opinion for those five justices and Chief Justice John Roberts in the wedding website (that wasn’t) case that created a First Amendment exemption to public accommodations nondiscrimination laws, and we arrive at 2024.

The Alabama Supreme Court’s attack on in vitro fertilization (IVF), a pair of attacks on marriage equality, and the attack on Nex Benedict in Oklahoma and their death the next day all emerge from the ideology of, devices employed by, and cases decided by this Supreme Court majority.

We ignore their connections and danger at the peril of all who do not want this to become our national reality.

On Feb. 16, the Alabama Supreme Court allowed wrongful-death lawsuits to proceed against a lab that allegedly negligently allowed the destruction of frozen embryos created for IVF purposes. In order to permit those lawsuits, the court first had to conclude that frozen embryos in a lab are children. The nine-member all-Republican court, with little difficult and only two dissenting justices, did so.

Much has been written about the first-of-its-kind decision, which has already led the state’s largest hospital to pause IVF treatments in the wake of the ruling. Significant attention has been given to Chief Justice Thomas Parker’s outright-theocracy concurring opinion, which it certainly deserves.

I’d like to focus instead on the majority opinion from Justice Jay Mitchell, which is extreme in its own ways — and highlights the dangerous faux-jurisprudence that the U.S. Supreme Court has encouraged.

In order to reach its ruling, the court needed to ignore its own past precedents that congruence between the state’s criminal-homicide statute and wrongful-death statute was needed. This is important because the state’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act was passed in 1872. The court had justified expanding that civil law to fetuses in utero based on an expansion of the criminal law to include fetuses in utero and the claimed need for congruence between the two laws. Now that the court wanted to go further than the criminal law, it just ignored those rulings — overruling them without saying so, as Justice Greg Cook stated in his dissenting opinion.

Or, as Justice Will Sellers wrote more bluntly, “To equate an embryo stored in a specialized freezer with a fetus inside of a mother is engaging in an exercise of result-oriented, intellectual sophistry, which I am unwilling to entertain.”

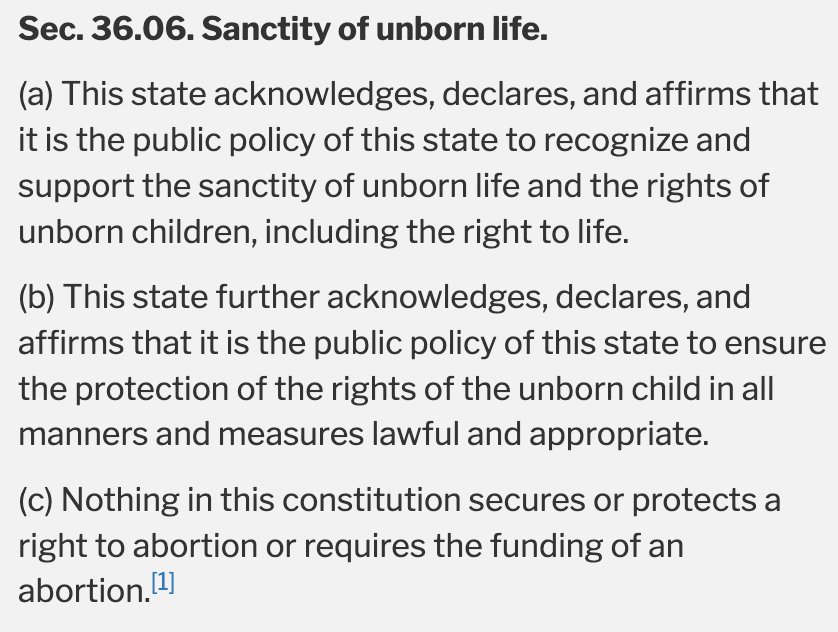

The court also went far afield of what was necessary for its ruling. After claiming that “[t]here is simply no … ambiguity” about the word “child” in the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act, the court then got into what ordinarily would then not have been a part of the opinion at all: An extended discussion of the “Sanctity of Unborn Life’ provision of the Alabama Constitution: Article I, Section 36.06.

Of that, Mitchell wrote for the court, “Even if the word ‘child’ were ambiguous, however, the Alabama Constitution would require courts to resolve the ambiguity in favor of protecting unborn life,” claiming that Section 36.06 “operates in this context as a constitutionally imposed canon of construction, directing courts to construe ambiguous statutes in a way that ‘protect[s] ... the rights of the unborn child’ equally with the rights of born children, whenever such construction is ‘lawful and appropriate.’“

This is dicta — a statement that is unnecessary to the ruling — and yet, as a statement in a majority opinion from the state’s Supreme Court, it was a chance for this court to establish this new rule, which undoubtedly will now be applied by lower courts in Alabama.

As Sellers wrote in dissent, “Respectfully, § 36.06 neither operates in such a fashion nor commands this Court to override legislative acts it believes ‘contraven[e] the sanctity of unborn life’“ — a quote from Parker’s even further-reaching concurring theocratic opinion.

Finally, and perhaps most telling, the court — in the closing paragraphs of Mitchell’s opinion — makes clear that it did not need to reach either the statutory or constitutional issues here.

“[T]he defendants pointed out that all the plaintiffs signed contracts with the Center in which their embryonic children were, in many respects, treated as nonhuman property,” Mitchell wrote. “If the defendants are correct on that point, then they may be able to invoke waiver, estoppel, or similar affirmative defenses.”

In other words, if this is true, the court could have issued a ruling that avoided all of the IVF issues — instead ruling that, even if the plaintiffs could bring such lawsuits, they would be barred from doing so here. This is an ordinary practice of courts to avoid reaching more complicated or extensive rulings than necessary for the case in front of it.

But, this court wanted to reach its broader ruling in this case. So, it refused to rule on that pivotal question, with Mitchell instead writing for the court, “[T]hose defenses have not been briefed and were not considered by the trial court, so we will not attempt to resolve them here. We are ‘a court of review, not a court of first instance.’”

Ignoring precedent, going further in its rulings than necessary, and reaching issues that it did not even necessarily need to reach — all in service of a ruling that restricts bodily, family, and reproductive autonomy to advance what Parker’s concurrence makes clear is a Christian nationalism goal.

On Feb. 21, Republican Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed into law a bill (H.B. 878) about marriage ceremonies that made news in 2023 and was punted to this year. This year, though, the very short bill quickly passed by the state’s extremely conservative legislature.

It seems a rather random law — until one sees the original language that made its purpose (slightly) more clear:

The law — animated by those opposed to same-sex couples’ marriage rights guaranteed in Tennessee by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision — doesn’t have an extensive immediate effect. It has no effect on the issuance of marriage licenses and many people are authorized under state law to solemnize marriages.

But, it is legislation that captures the spirit of both Dobbs and 303 Creative — and, more recently, a statement respecting a denial of certiorari issued by Alito on Monday.

The new Tennessee law is, as others have argued, reminiscent of the long-term strategy of the right to overturn Roe by chipping away at the right until, at some point, someone will argue that the underlying precedent (here, Obergefell) has been so undermined that it should be overruled.

The day before Lee signed the bill into law, the Supreme Court denied review in a case about whether people who believe being gay is a sin could properly be struck for cause from a jury in a case involving a lesbian suing her employer, Missouri’s Department of Corrections, for discrimination. Of the Missouri court’s decision to strike the jurors, Alito wrote that the decision “exemplified the danger that I anticipated in Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U. S. 644 (2015), namely, that Americans who do not hide their adherence to traditional religious beliefs about homosexual conduct will be ‘labeled as bigots and treated as such’ by the government.”

Of Obergefell, Alito then wrote, “The opinion of the Court in that case made it clear that the decision should not be used in that way, but I am afraid that this admonition is not being heeded by our society.”

Although this, like Tennessee law, is not a direct challenge to Obergefell, it is an effort to undermine it — particularly to the benefit of those people with “traditional religious beliefs,” as Alito put it.

In both situations, it takes tortured reasoning to create a scenario in which the person opposed to same-sex couples’ marriage rights — or, “homosexual conduct,” as Alito wrote — is somehow the wronged person needing protection.

With the Tennessee law, we’re talking about protecting government employees saying that they just don’t want to do their job when gay people come around. With the Missouri case, Alito is saying that it’s jurors who think lesbians are sinners who are the victims … in a lesbian’s discrimination case.

Religious adherents — particularly Christian conservative ones — deserve protections, Alito and this court keep insisting to us. Everyone else is out in the cold or, at least, on thin ice.

On Feb. 8, Nex Benedict died. There is much that we don’t yet know. But, what we do know paints a damning picture of the indifference and hate that has been unleashed in America, in not insignificant part under the blanket of this Supreme Court’s protection of (primarily Christian) religious beliefs and in the wake of its indifference to bodily autonomy. As I was preparing this report, Judd Legum at Popular Information published a must-read piece about where things stand.

We know that Nex’s mother, family, and friends are questioning the police and school’s statements about the fight that happened at their school the day before they died — which Nex reportedly told a friend was actually them getting “jumped at school 3 on 1” — and the police statements about their death.

We know that Oklahoma has passed anti-trans laws signed into law by Republican Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt and defended in court by Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond. We know that Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters — previously Stitt’s education secretary — is explicitly anti-trans.

We know that Walters appointed Chaya Raichik — the Libs of TikTok social media figure whose extreme anti-trans crusade has, NBC News reported, preceded bomb threats — to his Library Media Advisory Committee in January. We know that Raichik previously targeted a teacher in the school that Nex attended. We know the teacher, who provided a safe space for LGBTQ students in his classroom, was driven out of the school district.

We know that Nex faced bullying and was tormented because they identified as nonbinary in their time at Owasso Public Schools. We know that on Feb. 7, the fight happened and Nex reportedly texted a friend, “I got jumped at school 3 on 1 had to go to the ER.” We know the school did not contact the police or call for an ambulance — despite later recommending to one parent that “their student,” presumably Nex, get a medical examination.

We know that Nex’s mother took them to the hospital that day and Nex went home that night.

We know that Nex died the next day.

This is a horror that has disturbed me every time I think about it for the past week.

Four months before Nex died, on October 5, 2023, U.S. District Judge John Heil III, a Trump appointee to the federal bench in Oklahoma, became the first federal district court judge in the country to rule that a ban on gender-affirming medical care for minors was likely constitutional. These extreme laws restrict trans minor’s bodily autonomy and their parents’ rights to raise their children as they they think appropriate. The anti-trans rhetoric surrounding the laws is harsh and unforgiving. I cannot imagine being a person trying to get through my teenage years exploring and growing to understand my gender identity in this environment — but so many are.

As I wrote at the time, Heil’s ruling relied heavily on two appeals court rulings that represented the shifting landscape under which the law is operating in America — from Judges Jeffrey Sutton and Barbara Lagoa. Their rulings, in turn, relied upon cramped readings of several past Supreme Court decisions that other judges had found to be controlling in the challenges and a reach into one paragraph of Dobbs to upend — and minimize — sex discrimination protections. And, especially in Sutton’s opinion, the decision rested on a belief that all of this is just democracy at work and not a matter for the courts.

When challenges to these anti-trans laws began in 2021, however, their outcome — while seriously challenged by both sides — was remarkably consistent: Arkansas and Alabama bans were found to be likely unconstitutional and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit agreed as to the Arkansas law. That continued through and into 2023 until a July ruling from Sutton and Judge Amul Thapar.

The only changes were more of these laws passing, challenges reaching more ideological appeals courts, and the newly constituted Supreme Court — with its three Trump appointees — spreading its wings and overruling Roe.

More than 20 years ago, then-Justice Anthony Kennedy opened an opinion for the court with what seemed to me at the time to be unnecessarily flowery language about autonomy that I now see was essentially important to his understanding of the Constitution and its protections.

In striking down sodomy laws across the nation in 2003’s Lawrence v. Texas, Kennedy wrote, “Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct.”

Within that framework, the current Supreme Court majority has shown a disregard for “autonomy of self” when it comes to people’s actual bodies in overturning Roe — with all of the fallout discussed here and elsewhere — and the rights of many people from marginalized groups to participate in public life, even as it increases protections for those who wish to discriminate in the public sphere based on their religious beliefs.

The result is a nation where extremist far-right courts invoke more expansive and extreme arguments to rule on matters on an increasingly fast timeline — while this is the U.S. Supreme Court. Those rulings, in turn, encourage and free lawmakers, government employees, and private citizens to press further and further right. And, regardless of whether Nex Benedict died directly from their injuries sustained on Feb. 7, they died under the pains of living in a state and country where that extremism has been given that encouragement and freedom.

We must do better. This must change.

I weep for this country. I remember when Obergefell was decided - how we celebrated, the beautiful language and sentiments. Those were days when it felt like we were on the right track. Nasty, evil people like Alito and Thomas had to sit and sulk with their mean spirited little souls and ideas in the Bohemian Grove by themselves. And this is why we MUST make sure they stop being wined and dined by the people who want to drag us back to the 19th century. ENOUGH. Let’s abort the Republican party.

Alito's comment in his statement regarding Obergefell is an example of his bias.

There is nothing specific about same sex marriage that changes the overall question of religious liberty. Catholic doctrine has broad reach, including opposing remarriage after divorce and sex outside of religiously sanctioned marriage. Griswold, the contraceptives cases, was a product of Catholic supported legislation against use of birth control.

I clashed on a Catholic legal blog years back with those who wanted to provide a special extra burdensome rule regarding sexual orientation discrimination. Neutral concerns of religious liberty is not the issue here. Where was claimed need for state officials not to take part in "sanctifying" (a dubious term for secular laws) marriages in the past?

Many secular marriages clash with religious viewpoints. When a selective few are deemed problematic, we can be well suspicious of bias.