303 Creative: What we talk about when we talk about the wedding website (that isn't)

Part I: Preliminary matters, or, "What is up with that same-sex wedding request that Lorie Smith said she got?"

[Editor’s Note: Part II of Law Dork’s coverage of 303 Creative can be found here.]

There are two almost entirely separate discussions going on about the wedding website (that isn’t) case decided on June 30 by the U.S. Supreme Court.

There is a lot of discussion about the effects on public accommodation laws and possible fallout from the decision, and there are also important discussions about whether the court should have even heard the case.

The fallout questions are affected by the discussion of the preliminary matters, so today’s Law Dork will address those preliminary matters. Within those preliminary matters, there are four sometimes overlapping issues that are making the post-decision discussion of 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis extremely difficult.

First, and least objectionable: This is a pre-enforcement challenge.

There had been no enforcement of Colorado’s public accommodations law against Lorie Smith or her business, 303 Creative, prior to her filing her lawsuit. This isn’t unusual, and it is regularly a part of civil right litigation from the left. (Many of the challenges to anti-transgender laws passed in Republican-controlled states across the country this year are pre-enforcement challenges, to give just one timely set of examples.)

In such a case, the plaintiff needs to show that they face a “credible threat” that they state is going to enforce the law or policy in question against them and that doing so will infringe on their rights.

Smith alleged in her lawsuit that “she faces a credible threat that Colorado will seek to use CADA [Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act] to compel her to create websites celebrating marriages she does not endorse,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in his opinion for the 6-3 Supreme Court majority on June 30. “As evidence, Ms. Smith pointed to Colorado’s record of past enforcement actions under CADA, including one that worked its way to this Court five years ago,” referencing Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission.

Second, and slightly more questionable: Smith’s business had never made wedding websites before she sued.

This is a bit more unusual. This is, primarily, what people like Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern were discussing when they questioned the case back during oral arguments. As he wrote, “There is no live controversy, and therefore no facts against which the justices could test their legal theories.“

This is not a scenario where a longstanding business or medical practice or something sees the legislature passing a law and goes to court because the new law will directly target their business. This is the inverse: A person who has not been offering a service wants to start, but believes that doing so would violate existing state law. Nonetheless, Smith argued here that she should be able to bring this action because it’s ultimately not different from any ordinary pre-enforcement challenge.

That might be right as to legal standing, whether Smith and 303 Creative could be in court. But, the distinction could be more relevant to certiorari, the U.S. Supreme Court’s discretionary decision to take a case. The court chose to take this case. Sure, 303 Creative lost below, and the court’s majority clearly wanted to correct this. But, as the court’s conservatives often tell us: The Supreme Court is not a court of correction.

The court has had many cases with actual facts before it previously (including Masterpiece Cakeshop), which, if nothing else, should have signaled to the justices that they didn’t need to take this case if they wanted to address the legal questions.

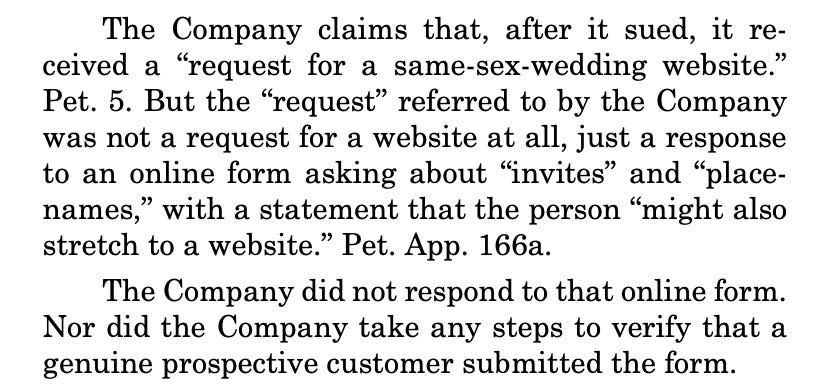

Third, and possibly a misstep by Colorado: The state stipulated — or, agreed for purposes of litigation — to many facts.

In his opinion for the court, Gorsuch highlighted several of the key stipulations.

Those are a lot of agreed-upon facts. And, importantly for the later discussion of fallout, many of those are facts that would be quite heavily contested — and, dare I say, unlikely to occur — in ordinary litigation. But, they weren’t contested here. So, for the purposes of the Supreme Court’s decision — and of justices’ consideration of the case — these are the facts of this case.

Finally, and most immediately confusing and possibly objectionable: The website request that (apparently) wasn’t.

This — the angle that began with Melissa Gira Grant’s story in The New Republic — is the late-breaking news that, in some corners, led to significant confusion about the case as it came down.

Before we go any further, let’s be clear: This was a failure of reporting — earlier in the case and certainly once cert had been granted at the U.S. Supreme Court. Particularly given how this case was being discussed — as a case with no same-sex couples able to describe how they were being discriminated against — it shouldn’t have taken until Grant’s report came out on June 29 for this discussion to begin. I, for one, take partial blame here.

With reporting now underway, though, what have we learned? This is about a request that Smith’s lawyers have said came in to 303 Creative back on September 21, 2016, a day after her lawyers with Alliance Defending Freedom filed her case.

The request in question, as included in the Joint Appendix submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court and partially redacted here, was as follows:

As TNR reported a day before the June 30 decision came down, Grant had spoken with Stewart about the request:

Yes, that was his name, phone number, email address, and website on the inquiry form. But he never sent this form, he said, and at the time it was sent, he was married to a woman. “If somebody’s pulled my information, as some kind of supporting information or documentation, somebody’s falsified that,” Stewart explained. …

“I wouldn’t want anybody to … make me a wedding website?” he continued, sounding a bit puzzled but good-natured about the whole thing. “I’m married, I have a child—I’m not really sure where that came from? But somebody’s using false information in a Supreme Court filing document.”

However, even TNR’s report acknowledged that we didn’t know that much — including whether Stewart is telling the “whole story.” And, I don’t think that’s to accuse him of anything; we just honestly don’t know what actually happened here.

After The New Republic piece on June 29, The Guardian’s Sam Levine followed up with a story on June 30. The Washington Post and Associated Press have since followed up as well. They reported some more contours and background matters, but no one has established anything definitive about the request’s origin — beyond that Stewart says in 2023 that he sent no such request in 2016.

For her part, however, Smith did sign an affidavit in 2017 in support of 303 Creative’s motion for summary judgment in the district court that referenced this “same-sex wedding” request from “Stewart.” That affidavit was also included in the joint appendix submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court. From the affidavit:

At the Supreme Court, Smith’s lawyers devoted just a half-sentence to the alleged request, noting that Smith “has already received at least one request for a same-sex wedding website.”

Colorado’s lawyers didn’t devote much more time, spending two paragraphs in the state’s Supreme Court brief detailing facts that were not disputed by Smith — that 303 Creative never responded to the online-form request.

If this request been key information before the court — particularly if it had been important to the court’s conclusion that it could hear the case — then this reporting could be a sign of a decision unraveling. But, it wasn’t. The appeals court found standing with no reliance on or reference to any claimed website requests. Oral arguments at the U.S. Supreme Court included no mention of any actual website requests. And, Gorsuch’s opinion for the court likewise included no mention of any actual website requests.

Where does all of that leave us?

As to the relevant legal issues — of whether Smith and 303 Creative had standing to bring the case, and whether the issue was “ripe” to be heard by the courts — the only real discussion of either in June 30’s Supreme Court opinions came in a very short section of Gorsuch’s opinion for the court.

And, that section both pulls together all of these preliminary questions and explains, ultimately, why the questions that remain regarding the website request are unlikely to have any effect on the June 30 decision in the case.

“For its part, the Tenth Circuit held that Ms. Smith had standing to sue. In that court’s judgment, she had established a credible threat that, if she follows through on her plans to offer wedding website services, Colorado will invoke CADA to force her to create speech she does not believe or endorse,” Gorsuch wrote, referencing the Masterpiece Cakeshop case and the state’s refusal to “disavow future enforcement” of CADA, including against Smith and 303 Creative. “Before us, no party challenges these conclusions.”

In other words, at the Supreme Court, standing was not really disputed by the parties. (In fact, the state’s short discussion of the website request came in its “statement of the case,” not in its argument section.)

To the extent any of this was discussed by Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her dissent, it did not appear to be to challenge or question standing, but rather as a set-up for the dissenters’ opposition to Smith’s lawsuit on the merits.

“The breadth of petitioners’ pre-enforcement challenge is astounding,” Sotomayor wrote, describing the “categorical exemption” Smith was seeking from CADA. “The sweeping nature of this claim should have led this Court to reject it.”

Final words — on these preliminary matters

While I wouldn’t rule anything out — because the known facts and public perception could change at any moment — what we know now isn’t enough for me to see any chance of the court withdrawing or altering its decision in 303 Creative.

But, if something more definitive were to be proven — if, for example, there were to be evidence that Smith’s lawyers knew that this was not a legitimate request — there could be ethical questions raised and individual consequences. In the most extreme situation, if something definitive and nefarious were to be proven, the circumstances could change at the Supreme Court. Outside, or even inside, pressure could force the court to take action in the case itself. I don’t expect that, but I can’t rule it out completely.

![To facilitate the district court’s resolution of the merits of her case, Ms. Smith and the State stipulated to a number of facts: Ms. Smith is “willing to work with all people regard- less of classifications such as race, creed, sexual ori- entation, and gender,” and she “will gladly create custom graphics and websites” for clients of any sex- ual orientation. App. to Pet. for Cert. 184a. She will not produce content that “contradicts bibli- cal truth” regardless of who orders it. Ibid. Her belief that marriage is a union between one man and one woman is a sincerely held religious convic- tion. Id., at 179a. All of the graphic and website design services Ms. Smith provides are “expressive.” Id., at 181a. The websites and graphics Ms. Smith designs are “original, customized” creations that “contribut[e] to the overall messages” her business conveys “through the websites” it creates. Id., at 181a–182a. To facilitate the district court’s resolution of the merits of her case, Ms. Smith and the State stipulated to a number of facts: Ms. Smith is “willing to work with all people regard- less of classifications such as race, creed, sexual ori- entation, and gender,” and she “will gladly create custom graphics and websites” for clients of any sex- ual orientation. App. to Pet. for Cert. 184a. She will not produce content that “contradicts bibli- cal truth” regardless of who orders it. Ibid. Her belief that marriage is a union between one man and one woman is a sincerely held religious convic- tion. Id., at 179a. All of the graphic and website design services Ms. Smith provides are “expressive.” Id., at 181a. The websites and graphics Ms. Smith designs are “original, customized” creations that “contribut[e] to the overall messages” her business conveys “through the websites” it creates. Id., at 181a–182a.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!77ZL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdbae82bf-35f8-4f3c-903a-04a15443918c_968x792.png)

![ Just like the other services she provides, the wed- ding websites Ms. Smith plans to create “will be ex- pressive in nature.” Id., at 187a. Those wedding websites will be “customized and tai- lored” through close collaboration with individual couples, and they will “express Ms. Smith’s and 303 Creative’s message celebrating and promoting” her view of marriage. Id., at 186a–187a. Viewers of Ms. Smith’s websites “will know that the websites are [Ms. Smith’s and 303 Creative’s] origi- nal artwork.” Id., at 187a. To the extent Ms. Smith may not be able to provide certain services to a potential customer, “[t]here are numerous companies in the State of Colorado and across the nation that offer custom website design services.” Id., at 190a. Just like the other services she provides, the wed- ding websites Ms. Smith plans to create “will be ex- pressive in nature.” Id., at 187a. Those wedding websites will be “customized and tai- lored” through close collaboration with individual couples, and they will “express Ms. Smith’s and 303 Creative’s message celebrating and promoting” her view of marriage. Id., at 186a–187a. Viewers of Ms. Smith’s websites “will know that the websites are [Ms. Smith’s and 303 Creative’s] origi- nal artwork.” Id., at 187a. To the extent Ms. Smith may not be able to provide certain services to a potential customer, “[t]here are numerous companies in the State of Colorado and across the nation that offer custom website design services.” Id., at 190a.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Nhvq!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3781a0cd-5ff9-4203-8318-1c022135d4bf_954x652.png)

Moot court is great training for advocacy and requires no pesky facts. Only hypotheticals. Like 303’s hypothetical business and its hypothetical plans to engage in the sale of its First Amendment protected rights of expression. She may as well claim that “someday I might become a photographer of prom nights and if I did and if a gay couple wanted their photo taken I can decline on First Amendment grounds, just as I could decline to take photographs of couples posing in lewd positions. My First Amendment in the latter case aligns with legal prohibitions against child pornography. But if they didn’t I should be free to exercise my First Amendment rights to celebrate the beauty of young love.” Colorado is not compelling 303’s speech. 303 can offer up a wedding package that makes no distinction in gender combinations and proclaim “I am the artist and you have no say in the matter of my artistic expression.” But if it says “hire us and we will help you realize your vision” is that still the speech of the business? Is every expressive act of a fictive person to be embraced by the protection of the First Amendment? “Sorry, we can’t seat you in our restaurant which is themed as a 1923 restaurant in Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi. Our artistic vision requires the utmost attention to strict historical accuracy, and you know that there is no circumstance under which a mixed race couple could ever have been seated in such an establishment.”

Thanks for pointing out that the pre-enforcement nature isn’t new and is also used for other challenges than the license for religious bigotry.

I honestly didn’t know this. I’m a little disappointed that this hasn’t been mentioned in MSM - maybe everyone knows this, but I didn’t.