Why would anyone trust Sam Alito?

Four times in Friday's opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, Alito insists marriage equality, gay sex, and contraception rights are safe. Why should we believe him?

Seven years ago, people were celebrating at the Supreme Court and the White House was drenched in rainbow in recognition of the court’s decision holding that bans on same-sex couples’ marriages were unconstitutional.

This Sunday, people were protesting outside the Supreme Court after the justices on Friday wiped a 49-year-old right off the books — by overturning Roe v. Wade and ending the constitutional right to an abortion — and gave states a roadmap to restrict abortions going forward.

Within minutes, lives were changed forever, as abortion clinics got word of the ruling and stopped performing abortions immediately. “We have reached the end of the line for abortion care,” the head of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri, the last clinic providing abortions in Missouri, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on Friday. The fallout was swift, but will not end there. There is already new litigation over existing anti-abortion laws, and there will be new laws and policies passed in the months to come.

I’ll be covering those developments extensively, but on the seven-year anniversary of Obergefell v. Hodges (the marriage equality case) and 19-year anniversary of Lawrence v. Texas (ending sodomy laws nationwide) — and as LGBTQ Pride Month comes to a close — I want to give some attention to the threat Justice Clarence Thomas issued to those rights in his concurring opinion on Friday.

In a section of his opinion that’s been circling the internet since Friday morning, Thomas urged the court to take up cases to overturn both Obergefell and Lawrence, as well as a case that even pre-dated Roe, Griswold v. Connecticut, which granted married couples the right to purchase contraception. (A later case that extended that right to unmarried couples, Eisenstadt v. Baird, also would, presumably, be tossed by Thomas once Griswold was gone.)

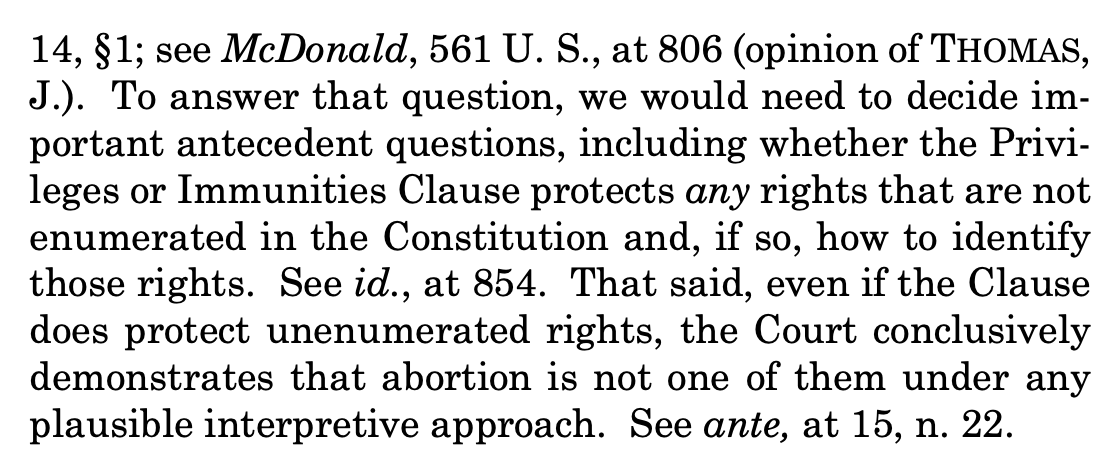

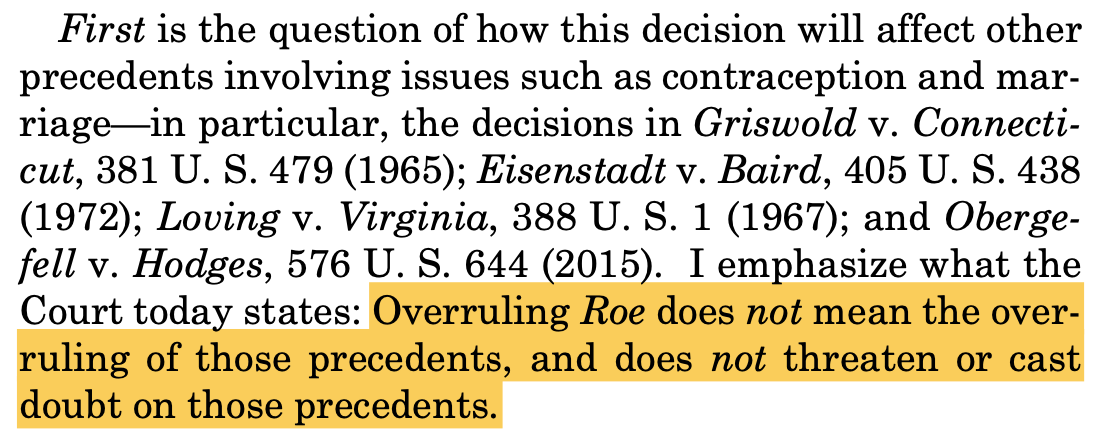

No other justices joined Thomas’s threat. Justice Samuel Alito, in fact, did his best — in multiple places in the majority opinion — to explain why overturning Roe would have no effect on those cases.

He explained that none of those other cases involve “potential life.”

He raised that distinction again in critiquing the dissenting opinion.

He raised the trio of cases a third time in responding to the concerns raised by the Biden administration in their brief supporting Roe. This is about abortion only, he insisted.

Finally, Alito raised it in a section more fully responding to the dissent. Here, he wrote for the court explicitly that “reliance” interests — dismissed on Friday in the abortion context — are “different for these cases.”

At one point, Justice Brett Kavanaugh echoes Alito in his concurring opinion:

So, it seems pretty clear that our contraceptives and sex lives and marriages are safe, right?

Not so fast.

The dissenters — Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, writing in a joint dissenting opinion — say otherwise: “[N]o one should be confident that this majority is done with its work.”

The trio lay out the legal case for why the majority cannot be taken at its word: The underlying rationale for getting rid of Roe, per the majority, is that the right to an abortion is not “deeply rooted in history.” Given the questioned historical approach taken by the majority in Dobbs, certainly a majority of this court could find a way to make the same case against contraception, same-sex sexual intimacy, and marriage equality if analyzed in the cramped way the conservative majority has chosen to analyze recognition of rights not named in the Constitution specifically.

All that said, and it’s a lot, there is also — particularly when it comes to actual people planning our actual lives — another very real question: Why would anyone trust Sam Alito?

Yes, it was the headline, and you had to read to here to get to this point, but it’s important that you saw what the justices said. Having read all of that, though, it’s just as important to understand that what happened on Friday significantly undermined what Alito and Kavanaugh claimed on Friday.

Think about it: In an opinion overruling 49 years of decisions — many of them — upholding Roe and, later, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, Alito and three of his other four reactionary colleagues want queer people to take them at their word that we should continue to organize our lives around 13-year-old and seven-year-old decisions.

I could make the case — and did, to friends, on Friday — that we’re unlikely to see an overruling of those cases and even more unlikely to see a step that would void existing marriages. That said, I added that if the far-right decides to make overturning those decisions their next goal in a way like they did with Roe and Casey, then that could change — quickly. (I also noted that the court’s aggressive religious supremacy moves are likely to lead to further religious exemptions to nondiscrimination laws and equality principles.)

This sense of doubt is one of the multitude of problems unleashed by the court on Friday.

I’ve written before about how a primary goal of having a legal system is to create stability and how the court was about to usher in a period of instability through its rulings. That is painfully, overwhelmingly the case now for women and other pregnant people — and their children, parents, families, friends, and co-workers (so, all of us).

Despite Alito and Kavanaugh’s words, their actions — certainly pushed along by Thomas’s rallying cry — have thrown other rights into question as well.

For LGBTQ people and their families, while rulings haven’t ended our constitutional protections under Lawrence and Obergefell, instability is nonetheless here.

!["... [im]peril those other rights, but the dissent’s analogy is objec- tionable for a more important reason: what it reveals about the dissent’s views on the protection of what Roe called “po- tential life.” The exercise of the rights at issue in Griswold, Eisenstadt, Lawrence, and Obergefell does not destroy a “po- tential life,” but an abortion has that effect. So if the rights ..." "... [im]peril those other rights, but the dissent’s analogy is objec- tionable for a more important reason: what it reveals about the dissent’s views on the protection of what Roe called “po- tential life.” The exercise of the rights at issue in Griswold, Eisenstadt, Lawrence, and Obergefell does not destroy a “po- tential life,” but an abortion has that effect. So if the rights ..."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!r7CU!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdd061724-5731-4795-be8c-3e93f88319bc_1118x296.png)

!["Unable to show concrete reliance on Roe and Casey them- selves, the Solicitor General suggests that overruling those decisions would “threaten the Court’s precedents holding that the Due Process Clause protects other rights.” Brief for United States 26 (citing Obergefell, 576 U. S. 644; Law- rence, 539 U. S. 558; Griswold, 381 U. S. 479). That is not correct for reasons we have already discussed. As even the Casey plurality recognized, “[a]bortion is a unique act” be- cause it terminates “life or potential life.” 505 U. S., at 852; see also Roe, 410 U. S., at 159 (abortion is “inherently dif- ferent from marital intimacy,” “marriage,” or “procrea- tion”). And to ensure that our decision is not misunderstood or mischaracterized, we emphasize that our decision con- cerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion." "Unable to show concrete reliance on Roe and Casey them- selves, the Solicitor General suggests that overruling those decisions would “threaten the Court’s precedents holding that the Due Process Clause protects other rights.” Brief for United States 26 (citing Obergefell, 576 U. S. 644; Law- rence, 539 U. S. 558; Griswold, 381 U. S. 479). That is not correct for reasons we have already discussed. As even the Casey plurality recognized, “[a]bortion is a unique act” be- cause it terminates “life or potential life.” 505 U. S., at 852; see also Roe, 410 U. S., at 159 (abortion is “inherently dif- ferent from marital intimacy,” “marriage,” or “procrea- tion”). And to ensure that our decision is not misunderstood or mischaracterized, we emphasize that our decision con- cerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!74oy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4640e593-6e9a-46c7-9b77-43fed415fcea_1108x778.png)

!["Finally, the dissent suggests that our decision calls into question Griswold, Eisenstadt, Lawrence, and Obergefell. Post, at 4–5, 26–27, n. 8. But we have stated unequivocally that “[n]othing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” Supra, at 66. We have also explained why that is so: rights regard- ing contraception and same-sex relationships are inher- ently different from the right to abortion because the latter (as we have stressed) uniquely involves what Roe and Casey termed “potential life.” Roe, 410 U. S., at 150 (emphasis de- leted); Casey, 505 U. S., at 852. Therefore, a right to abor- tion cannot be justified by a purported analogy to the rights recognized in those other cases or by “appeals to a broader right to autonomy.” Supra, at 32. It is hard to see how we could be clearer. Moreover, even putting aside that these cases are distinguishable, there is a further point that the dissent ignores: Each precedent is subject to its own stare decisis analysis, and the factors that our doctrine instructs us to consider like reliance and workability are different for these cases than for our abortion jurisprudence." "Finally, the dissent suggests that our decision calls into question Griswold, Eisenstadt, Lawrence, and Obergefell. Post, at 4–5, 26–27, n. 8. But we have stated unequivocally that “[n]othing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” Supra, at 66. We have also explained why that is so: rights regard- ing contraception and same-sex relationships are inher- ently different from the right to abortion because the latter (as we have stressed) uniquely involves what Roe and Casey termed “potential life.” Roe, 410 U. S., at 150 (emphasis de- leted); Casey, 505 U. S., at 852. Therefore, a right to abor- tion cannot be justified by a purported analogy to the rights recognized in those other cases or by “appeals to a broader right to autonomy.” Supra, at 32. It is hard to see how we could be clearer. Moreover, even putting aside that these cases are distinguishable, there is a further point that the dissent ignores: Each precedent is subject to its own stare decisis analysis, and the factors that our doctrine instructs us to consider like reliance and workability are different for these cases than for our abortion jurisprudence."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hl0V!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F46bfb7e9-a53c-49be-962d-eda0ccd86905_1102x970.png)

![to rights of same-sex intimacy and marriage. They are all part of the same constitutional fabric, protecting autonomous decisionmaking over the most personal of life decisions. The majority (or to be more accurate, most of it) is eager to tell us today that nothing it does “cast[s] doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” ... But how could that be? The lone rationale for what the majority does today is that the right to elect an abortion is not “deeply rooted in history." ... The same could be said, though, of most of the rights the majority claims it is not tampering with. ... So one of two things must be true. Either the majority does not really believe in its own reasoning. Or if it does, all rights that have no history stretching back to the mid-19th century are insecure. Either the mass of the majority’s opinion is hypocrisy, or additional constitutional rights are under threat. It is one or the other. to rights of same-sex intimacy and marriage. They are all part of the same constitutional fabric, protecting autonomous decisionmaking over the most personal of life decisions. The majority (or to be more accurate, most of it) is eager to tell us today that nothing it does “cast[s] doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” ... But how could that be? The lone rationale for what the majority does today is that the right to elect an abortion is not “deeply rooted in history." ... The same could be said, though, of most of the rights the majority claims it is not tampering with. ... So one of two things must be true. Either the majority does not really believe in its own reasoning. Or if it does, all rights that have no history stretching back to the mid-19th century are insecure. Either the mass of the majority’s opinion is hypocrisy, or additional constitutional rights are under threat. It is one or the other.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fQaU!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F13755c9d-a469-4a59-91c7-b7ea224229dc_1102x1180.png)