A new, old type of lawlessness as Trump attacks Venezuela — and an opening for a better America

The legal discussion is dark in the wake of the U.S. military taking Nicolás Maduro to the U.S. The path America is on today, however, is not where we need to go.

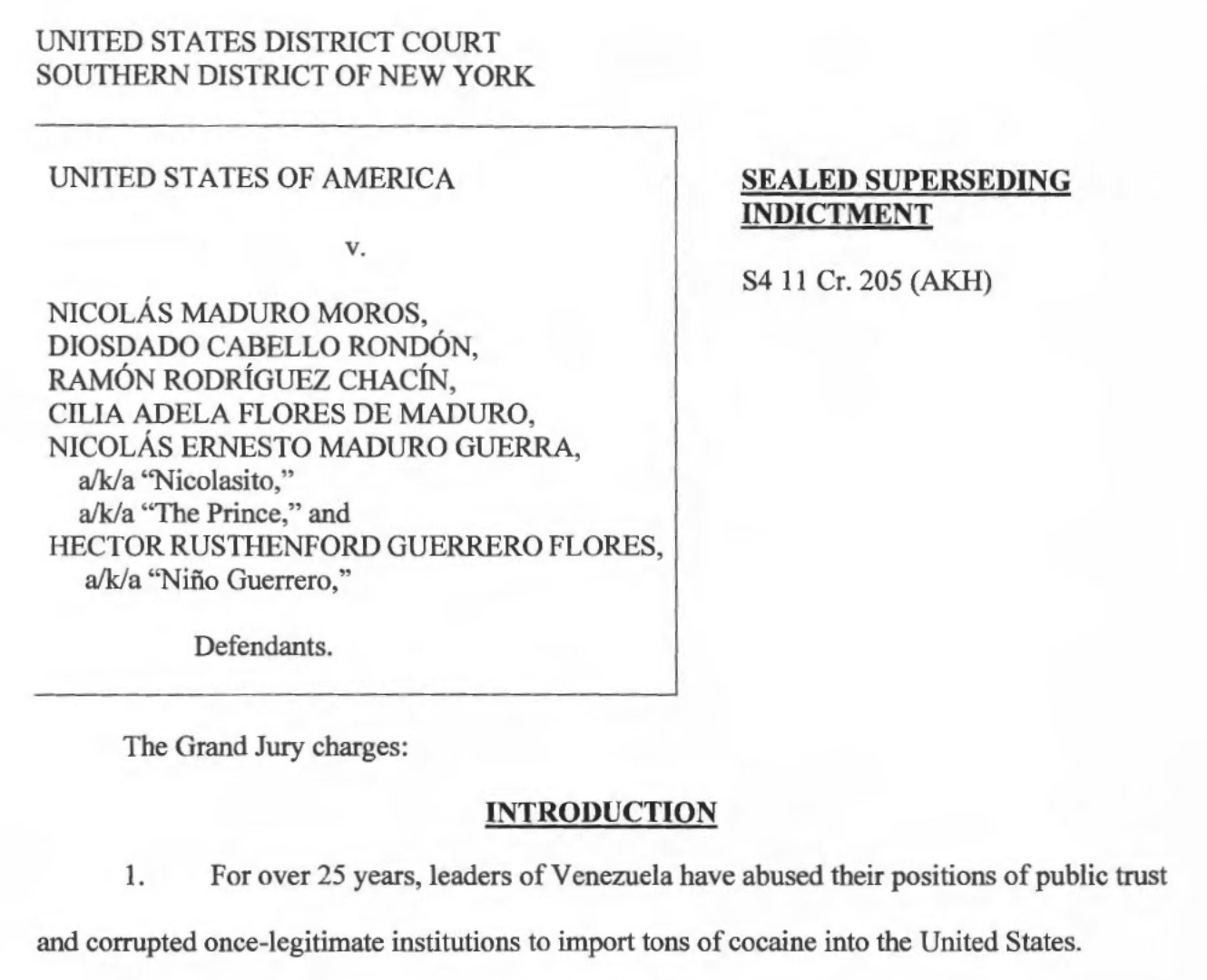

Overnight, the United States entered the sovereign territory of a foreign nation; bombed several areas; invaded its president’s compound; took that man and his wife from their house; and brought them to New York, where they face longstanding drug trafficking charges.

In a news conference from Mar-a-Lago on Saturday, President Donald Trump expanded the consequences and scope of the operation even further, saying of Venezuela, “We’re gonna run it … until such time as a proper transition can take place.”

Then, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Dan Caine, warned: “There is always a chance that we’ll be tasked to do this type of mission again.“

This all happened under Trump’s command, and it represents something that is both unfamiliar — and all too familiar — to American history. The unique nature of Trump’s invasion and decapitation of the government in Venezuela masks what makes it less exceptional: It combines many aspects of things that the United States has done in its history — but all in one night.

The United States has invaded foreign countries before when it faced no imminent threats. The United States has taken out foreign leaders before. The United States has even put foreign leaders on trial before. And, more familiar, the United States has definitely engaged in “nation-building” before.

The closest the United States has come to doing what happened on Saturday was exactly 36 years ago — when the United States apprehended Panamanian General Manuel Noriega on January 3, 1990 and brought him to America to face drug charges in Florida.

This time around, the United States apprehended Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on January 3, 2026 and brought him to America to face drug charges in New York.

The complicated nature of this moment centers on two aspects — a legal discussion, which this post will describe at length, as well as a normative discussion, on which I will end.

Where we are is an extremely difficult moment, and that is reality, but it need not be where we go. In this moment, then, there is a chance to create a better America, as hard as that might be to see this weekend.

The legal opinions

The legal response to Trump’s actions includes two pieces that, at first blush, appear to be quite divergent.

In Georgetown Law professor Steve Vladeck’s post at One First …

… he distinguished the Noriega operation as such:

In the Panama example, the Panamaian general assembly had formally declared a state of war against the United States, and a U.S. Marine had been shot and killed, before President George H.W. Bush authorized the underlying operation.

Further, he continued:

[E]ven then, there’s still nothing approaching consensus that Operation Just Cause was actually consistent with U.S. law; Congress passed no statute authorizing hostilities, and it was hard to see how the situation in Panama posed any kind of imminent threat to U.S. territory sufficient to trigger the President’s Article II powers—just like the Trump administration’s narco-trafficking claims seem difficult to reconcile with where fentanyl actually comes from (Mexico) or the Trump administration’s own behavior (like pardoning former Honduran president-turned-cocaine-trafficker Juan Orlando Hernández).

Vladeck’s conclusion: “In other words, the only real precedent for what happened Friday night doesn’t provide any legal support for the United States’ actions.”

Vladeck, in his post, went on to discuss the questions remaining — including how the Maduro prosecution will proceed, what happens in Venezuela (a matter complicated by Trump’s comments that the U.S. plans to “run” the nation in the interim), and an interesting look at the ongoing Alien Enemies Act litigation.

As he concluded about the operation itself, however, the most likely outcome is that “a blatantly unlawful use of military force overseas will go un-remedied—because there’s no viable legal pathway to challenge it.“

That takes us to Harvard Law School professor Jack Goldsmith, whose post at Executive Functions …

… ultimately reaches the same conclusion through a very different framing.

It is, for the most part, descriptive. As Goldsmith wrote of “reality” at the outset to frame his piece:

Congress has given the president a gargantuan global military force with few constraints and is AWOL in overseeing what the president does with it. Courts won’t get involved in reviewing unilateral presidential uses of force. And no country plausibly could stop the U.S. action in Venezuela.

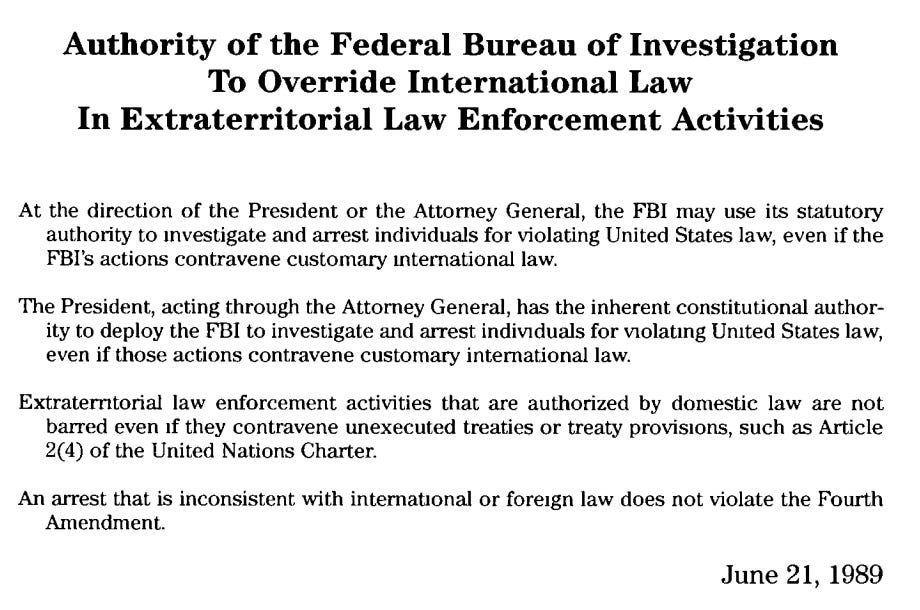

Goldsmith, looking at the facts and history and state of the law, explained how the “Justice Department, if asked, easily could have drafted an opinion based on … [executive branch] precedents and [legal] opinions to justify the invasion of Venezuela.“

In short, given our Congress and our courts, it is not an uplifting post for those wanting action — wanting a quick response to this administration. This also is not to say that Goldsmith backs that reality — to the contrary, he refers to the “promiscuously generous executive branch legal opinions” in his conclusion — but it is, in his view as the former head of the Office of Legal Counsel that authors such opinions, the reality.

Noting that some would “seek to distinguish” the Noriega example from this weekend’s actions, Goldsmith wrote:

[T]he Panama precedent will nonetheless matter to the Venezuela attack due to this 1989 opinion by then-Assistant Attorney General Bill Barr, issued six months before the invasion. That opinion justified FBI arrests in foreign countries under domestic law even if doing so violated international law.

Yes, that Bill Barr.

Vladeck, too, cited that June 21, 1989 OLC opinion — calling it “a deeply controversial” one, but nonetheless noting its likely role in at least being used by the Trump administration to seek to justify this operation.

In Venezuela, the CIA was apparently used to investigate and the military used to carry out the abduction, but both Vladeck and Goldsmith point to the 1989 memo as the opinion giving life to this part of the operation.

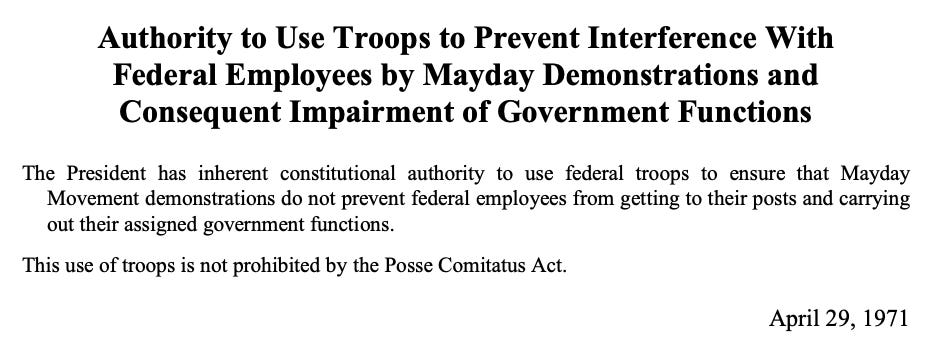

Vladeck and Goldsmith also address the larger, related military activity that took place overnight, with Vladeck citing a 1971 OLC opinion from William Rehnquist — yes, that William Rehnquist — for “DOJ’s longstanding view that the President has inherent constitutional authority to use military force to protect federal institutions and officers in the exercise of their federal duties.”

[Yes, if you’re paying close attention, this opinion also has come up in the litigation over the troop deployment in D.C. (See page 38 of U.S. District Judge Jia Cobb’s opinion in that case for more.)]

This “inherent authority” argument, however, also brought both men to the idea of “unit self-defense,” in which both Vladeck and Goldsmith rely on the work of Cardozo School of Law professor Rebecca Ingber in different ways. In “Legally Sliding Into War,” she wrote:

Unit self-defense is defense not of the state itself, but of the state’s armed forces. And it is a significant mechanism for escalation of conflict, whether intentional or not.

As Vladeck wrote, Ingber “has written in detail about why the “unit self-defense” argument is effectively a slippery slope toward all-out war, and she’s right.“

Of the use of “unit self-defense” in a situation like the one Trump ordered on Friday, Goldsmith wrote:

Yes, it seems like bootstrapping, or worse, to say that the United States can arrest a foreign dictator on foreign soil in violation of foreign sovereignty and then invoke the self-defense of the arresting forces to bomb the country. But this is where the logic of the executive branch precedents leads.

Caine all but admitted on Saturday at the Mar-a-Lago news conference that such “bootstrapping” was exactly what the administration believed — or, at least, would argue — justified its actions, announcing, “On arrival into the target area, the helicopters came under fire, and they replied to that fire with overwhelming force in self-defense.“

There is a lot in Goldsmith, Vladeck, and Ingber’s writings that revolve around the “reality” of “where the logic of the executive branch precedents” lead because, again, aspects of what happened this weekend are how America has operated at times, building up examples and precedents and opinions that Trump is now rolling together like a child building a giant snowball to exert the most extreme expansion of executive power he can amass.

Where does all of this leave us?

The question for Saturday night and moving forward is not so much a question of “reality” today as it is a question of what America should — and could — be.

While Vladeck concluded with his understandable concern about a world “in which we’re acting as little more than a bully, and in circumstances in which no obvious principle of self-defense, human rights, or even humantarianism [sic] writ large justifies our bellicosity“ — and the “price we’ll pay“ for that — I think Goldsmith provides an opening to something else.

Goldsmith wrote:

This is not the system the framers had in mind, and it is a dangerous system for all the reasons the framers worried about. But that is where we are—and indeed, it is where we have been for a while.

Those first 10 words — while looking all the way back to the beginning — point out a path forward.

Where we “are” today is not where we need to go.

Although it has been clear for a while now that major changes — even, potentially, constitutional changes — will be needed to move America beyond this moment, Trump’s actions over this weekend, building on the lawless boat-strike murders, create a global, moral imperative to do so. This is all the more clear given Caine’s comments that this could happen again.

The future American presidency does not need to — and cannot — look like the presidency that Trump is creating from the precedents of some of the United States’s most questionable international actions. Trump’s domestic actions — including impoundment, troop deployment, and efforts to unilaterally dismantle legally created entities, to name just three examples — will require changes for running the nation at home as well.

To move beyond this is an enormous task, and this weekend — if nothing else — should crystallize for people how serious and necessary that task is.

The next question, then, is just as serious: Who are the leaders up to that task?

Can’t help remembering the overthrow of Allende … and its outcome: Pinochet’s reign of terror.

The UN — and the rest of the world — care little for internal US documents and OLC opinions that sanction by any legal standard a blatant violation of another nation's sovereignty...why would Canada, the EU, or other countries give two fucks about a 1989 Wm. Barr opinion, for god's sake? I mean, if fucking trump wants to annex Greenland, sure, there will be memos and shite waved around FOR INTERNAL CONSUMPTION ONLY justifying it, but the ROW is confronting a rogue superpower led by a lawless regime, and whatever "constitutional" brakes on such crude imperialism, or the UN Charter itself which may *theoretically* constrain such behavior, but who's to enforce it? Who "sanctions" a fucking runaway superpower? NOBODY, and case closed.

Great start to Year Two of trump 2.0.