Following SCOTUS, Trump's birthright citizenship EO still faces skeptical courts

As the clock ticks down on SCOTUS's 30-day delay, the administration is blocked from enforcing the executive order under at least one classwide preliminary injunction.

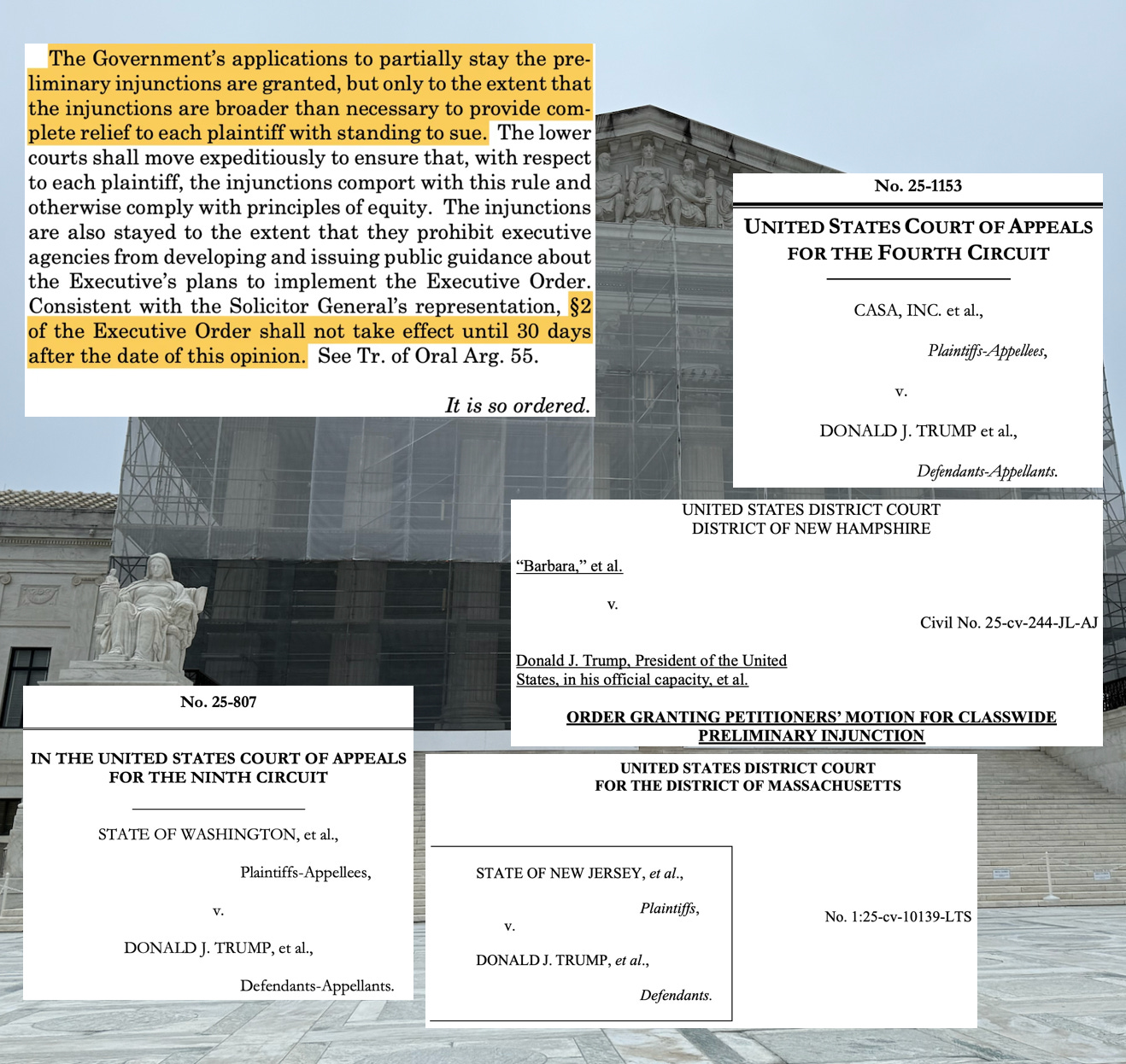

When the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hold oral arguments in May over the scope of the injunctions issued in cases challenging President Donald Trump’s executive order ending birthright citizenship, it appeared that the court was moving quickly to resolve the questions prompted by the president’s unprecedented action.

When the Supreme Court decision came down on June 27, “universal injunctions” were out and a 30-day clock began running on when Trump’s policy was set to go into effect.

As the clock ticks down to July 27, however, the administration is currently blocked from enforcing the executive order — under at least one classwide preliminary injunction and, by my read, under multiple court orders.

What’s more, for the time being at least, there no apparent movement from the administration to get the issue back in front of the Supreme Court any time soon.

At the same time, however, the administration has been fighting in the lower courts and making some extreme arguments — even as to the procedural posture of the cases — so nothing is certain here. Additionally, the administration, under the Supreme Court’s order, has been allowed to “develop[] and issu[e] public guidance about the Executive's plans to implement the Executive Order,” so there could be consequences of that becoming apparent — and prompting further challenges — in the coming days.

So, what’s going on?

The first thing to know is that the Supreme Court did not end the possibility of an injunction that would have nationwide coverage. There were two primary ways that could happen — and both are at issue now in the four of the five key challenges to the birthright citizenship order.

And, yes, as every court to address the merits of the executive order has concluded: This is unconstitutional. And yet, here we are.

Multistate actions

The Supreme Court noted that injunctions with nationwide effect could be permitted when nationwide relief is necessary to provide the plaintiffs with complete relief. In the two cases brought by groups of states, the Supreme Court held that the “lower courts” would need to address whether those injunction were appropriate in those two cases.

As of Wednesday, there is no order limiting those injunctions.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit had sought supplemental briefing after the Supreme Court’s ruling, and the states led by Washington state and Trump administration provided the briefing on July 11. There has been no responsive order from the court.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, however, sent the other multistate case — led by New Jersey — back to U.S. District Judge Leo Sorokin, an Obama appointee, to resolve the effect of the Supreme Court’s order on the injunction. Following a July 2 order from Sorokin, DOJ filed a brief advancing their view, the New Jersey-led states filed a response, and DOJ filed its reply onJuly 17.

Now, I should be clear that DOJ is playing some word games here, although, I’m not sure to what end. From their brief in the second case:

[T]he Supreme Court was clear that it “granted” a partial stay to the extent the preliminary injunctions issued by this and other courts “are broader than necessary to provide complete relief to each plaintiff with standing to sue.” There is therefore a stay in effect, the scope of which the Supreme Court required the lower courts to resolve. … [T]he briefing schedule proposed by the States and adopted by this Court flips the burden of proof: In light of the Supreme Court’s grant of Defendants’ stay, it is the States’ burden, in the first instance, to demonstrate why this Court’s preliminary injunction is necessary to remedy their injuries without being overly broad. Defendants do not have the obligation to prove the negative. Thus, nothing requires Defendants to affirmatively seek further relief for the CASA stay to apply, but to the extent this Court disagrees, Defendants request that this Court construe this filing as a motion to modify the preliminary injunction or as a motion to stay the preliminary injunction in part.

A lot of words, but, essentially, DOJ argued that, even though the Supreme Court’s majority opinion by Justice Amy Coney Barrett explicitly noted that the court wasn’t resolving whether the scope of the injunctions in the multistate cases were appropriate, the “partial” grant of a stay somehow would default to “the CASA stay … apply[ing]“ and somehow resolving the question Barrett wrote that the court did not resolve.

Here was what Barrett wrote for the court:

The Government's applications to partially stay the preliminary injunctions are granted, but only to the extent that the injunctions are broader than necessary to provide complete relief to each plaintiff with standing to sue.

If an injunction is not “broader than necessary to provide complete relief to each plaintiff with standing to sue,” it is not stayed.

The states have a strong response, both as to the insufficiency of the Trump administration’s filing and on the merits of the states’ claims:

[O]n the central question now before this Court—whether there are alternative ways to grant the States complete relief short of a nationwide order—Defendants come up empty. They largely complain that they should not bear a “burden” to explain how the alternatives they have been proffering to the First Circuit and Supreme Court for months could or would actually work or ensure complete justice. Defendants offer zero factual information, let alone declarations, to demonstrate their alternatives could do so, meaning nothing undermines this Court’s past findings that a nationwide order is needed for complete relief. To the contrary, a voluminous and compelling record confirms that a nationwide order is necessary

Sorokin held a hearing on July 18, and no order has yet been issued.

Class actions

The other way that relief could have nationwide effect — discussed explicitly in the CASA ruling — is through class-action litigation. It is more complex litigation that involves additional steps, but judges have already shown that it can proceed quickly.

In the CASA case at the center of the June 27 order, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint seeking class certification and a temporary restraining order later that day. Because the earlier case had been appealed, however, U.S. District Judge Deborah Boardman eventually found that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit would have to return jurisdiction of the case to her for her to issue any order in the matter.

At the same time, on July 16, Boardman, a Biden appointee, issued an “indicative ruling” — essentially, explaining how she would rule if she had the case — that she would grant “a class-wide preliminary injunction“ if she had jurisdiction to do so. The next day, the plaintiffs went to the Fourth Circuit, asking for the court to grant “a limited remand while retaining jurisdiction over the appeal, so that the district court can grant class-wide preliminary injunctive relief.“ That day, the Fourth Circuit ordered a response from DOJ by this Thursday.

But, in the final of the four key cases pending — a new class action case filed the day of the CASA Supreme Court ruling — there was very fast initial action. And then, nothing from DOJ.

After a status conference June 30, quick briefing, and a hearing July 10, U.S. District Judge Joseph Laplante granted provisional class certification and a classwide preliminary injunction that day — following the brief orders up with a more reasoned opinion that night. Laplante, a George W. Bush appointee, provisionally certified the following class, which tracks the children whose citizenship would not be recognized under Trump’s executive order:

The next day, the plaintiffs paid the $1 bond Laplante required of them.

Since then, DOJ has taken no action to appeal the order — despite Laplante’s apparent belief, as evidenced in his ruling, that an appeal would be coming quickly.

One final case

As all of this is going on, DOJ unsuccessfully tried (twice) to delay consideration of an appeal in another case challenging the executive order — and the result is potentially key arguments on the executive order next week.

This is a merits appeal of a preliminary injunction issued on Feb. 10, also by Laplante.

Because no universal injunction was at issue in the case, brought by New Hampshire Indonesian Community Support, the case was not held up by the CASA case consideration at the Supreme Court. As such, briefing continued at the First Circuit over the summer — with DOJ filing its lead brief in May, the plaintiffs filing their response in June, and DOJ filing its reply in July.

In this appeal, DOJ is arguing, in part, “The Executive Order Is Consistent with the Original Meaning of the Citizenship Clause.“

The plaintiffs, counter, simply, “The Order Violates the Fourteenth Amendment … because “[t]he Citizenship Clause is clear.“ It also, they note, violates federal law.

In short, while the big cases are being litigated over the scope of the efforts to stop Trump’s executive order, the constitutionality of the executive order itself could be decided in a much more narrow case.

Oral argument in that case is set for 3:00 p.m. August 1 in Boston.

I’ll admit that I don’t understand much of this. How can any President eliminate via an EO, a Constitutional amendment?

No legal eagle I - obviously - but my theory is that Trump’s handlers will go only so far in backing his petty revenge cases … saving the Big Guns to litigate to “more important” (to them) Project 2025 defense.