Federal judge blocks Trump's anti-trans military ban as "soaked in animus"

Finding the ban is likely unconstitutional on several grounds, Judge Reyes's injunction blocking the ban goes into effect Friday unless a higher court stays her order.

In his first month back in office, President Donald Trump made attacking transgender people an opening salvo in his ongoing attempts to wipe out civil rights protections in this country — or use them against those intended to be protected by those laws.

On Tuesday, just shy of two months of Trump back in office and following multiple days of intense hearings over several weeks, U.S. District Judge Ana Reyes issued a preliminary injunction stopping one of those efforts: Trump’s attempt to ban transgender people from the military.

“Defendants must show that the discriminatory Military Ban is in some way substantially related to the achievement of [the government’s stated] objectives. And they must do so without relying on ‘overbroad generalizations about the different talents, capacities, or preferences of males and females,’” Reyes wrote in her 79-page opinion in the case, quoting the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision requiring women’s admittance to the Virginia Military Institute. “They do not come close.“

Reyes found that the policy likely unconstitutionally discriminates against transgender people on the basis of sex and transgender status. And though she found that both are subject to heightened scrutiny, and that the policy would fail under that standard, she also found that the ban was motivated by animus and would be unconstitutional even if subject only to rational basis review.

“The Military Ban is soaked in animus and dripping with pretext,” she wrote. “Its language is unabashedly demeaning, its policy stigmatizes transgender persons as inherently unfit, and its conclusions bear no relation to fact.“

As such, she issued a preliminary injunction set to go into effect at 10 a.m. Friday.

Trump issued his first anti-trans executive order — purporting to define “sex” for the federal government — on his first day back in office. Seven days later, he issued his anti-trans military executive order. The lawsuit in front of Reyes was filed the next day. After briefing, hearings in front of Reyes, the military’s issuance of its policy, more briefing, and more hearings, Reyes issued her opinion and order blocking the ban’s implementation.

“To obtain an injunction, Plaintiffs must establish a likelihood of success on the merits. They have done so. The Court’s factual findings, the vast majority conceded by Defendants and all supported by the Record, make it highly unlikely that the Military Ban will survive judicial review, whether it be rational basis or intermediate scrutiny,” Reyes, a Biden appointee who had already gotten pushback from the leadership at the Justice Department before this Tuesday’s ruling, wrote.

The order

Her order blocks the military from implementing the executive order and military policies implementing it:

Military leaders are required under Reyes’s preliminary injunction to maintain the Biden administration policy — referred to as the Austin Policy throughout the opinion, for Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin — for recruitment and retention of trans service members:

At the same time, however, Reyes issued a little more than a two-day stay of her order — which she explained in her opinion is “to provide Defendants time to consider filing a motion for an emergency stay in the [U.S. Court of Appeals for the] D.C. Circuit.“

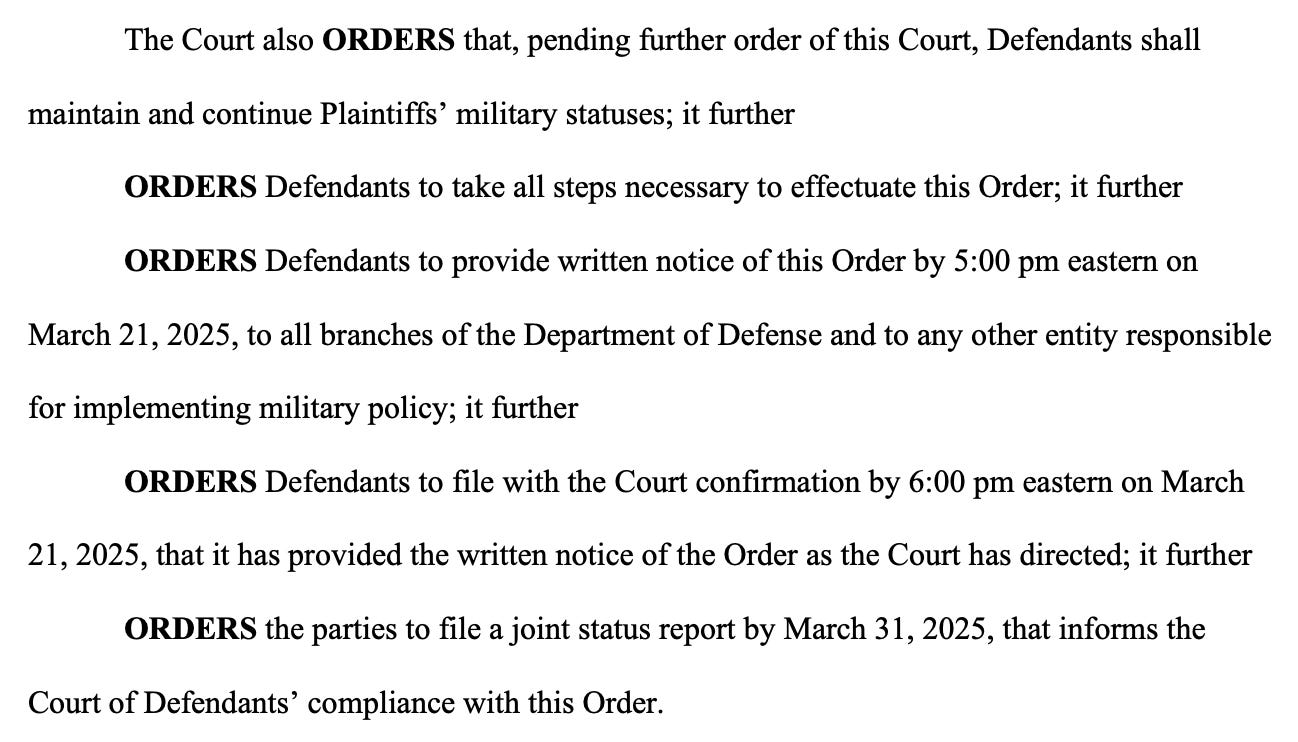

In the absence of a stay, however, Reyes also set a quick timeline Friday for military leaders — the defendants here — to notify anyone responsible for implementing the ban of her order. And, thereafter, to let the court know that they have done so.

In a note further reflective of federal judges’ responses to the new Trump administration, Reyes closes with a “come back to me if you have any questions about this order” note.

This follows the significant questions out of other orders in other cases in the D.C. District Court in recent days.

The opinion

The government’s primary argument here is deference to military decisions. But, as Reyes put it:

Defendants’ position does not urge judicial deference to military judgment. It urges judicial abdication. No. The law does not demand that the Court rubber-stamp illogical judgments based on conjecture. …

Notwithstanding the deference the Court owes it, the military still must show that burdening these Plaintiffs’ equal protection rights is related to furthering a government interest. And as discussed throughout this opinion, the military’s justifications “come up very short.”

Noting the rapid pace with which the military implemented the policy and the government’s lack of answers to questions about justifications for the policy, Reyes highlighted that “Defendants rely heavily on Trump v. Hawaii” — the eventual U.S. Supreme Court ruling upholding Trump’s third travel ban during his first administration. But, she continued, that “reliance is misplaced.” As she discussed in the hearings, Reyes saw that case actually as a key way of highlighting how improper what the government did here was.

She did so with a side-by-side comparison:

With that down, Reyes went on to address and find that the plaintiffs are likely to succeed in their arguments that the ban classifies both on sex and transgender status and that it does so unconstitutionally.

Addressing the plaintiffs’ claim that the ban classifies based on sex, Reyes turned to the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, holding 6-3 in an opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch and joined by Chief Justice John Roberts that the sex discrimination ban in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 includes bans on discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Reyes explained what I’ve been writing about for some time now: “The Court agrees with Defendants that Bostock’s holding is cabined to Title VII. … But its reasoning is not. The Supreme Court deduced it impossible—end stop—to discriminate against a transgender person without discriminating against that person based on sex.”

Applying that to the military ban, Reyes wrote:

The Military Ban excludes from service transgender women because they are biologically male but identify as women. Had those very same servicemembers been born female, the military would not ban them. Is this discrimination on the basis of sex? The test is simple: would changing that transgender soldier’s sex lead to a different decision by the military? Yes, a biological female who identifies as a woman is not banned. Ergo, discrimination.

Reyes also found that the ban classifies on the basis of transgender status and that such classifications should, like sex, be subject to heightened scrutiny under the Supreme Court’s test for assessing whether heightened scrutiny applied.

Applying heightened scrutiny — in which the government must provide evidence that its policy is substantially related to advancing an important governmental interest — Reyes noted the three categories of the government’s evidence: “(1) military readiness, (2) unit cohesion, good order, and discipline, and (3) disproportionate costs.” She then addressed what she called “the lack of any connection between Defendants’ evidence and the Military Ban’s directives.” Additionally — and though discussed at length later in the opinion — she found that “the Military Ban is littered with animus and pretext.”

As part of this consideration, Reyes also found that the government’s “exemption,” the “waiver” provision, is not really an exemption at all:

Discussing the complete lack of evidence presented by the military to justify such an extreme step, Reyes — after discussing the fact that “the Military Ban covers those who even ‘exhibit symptoms consistent with[] gender dysphoria’” — wrote:

Even if the Military Ban had focused solely on those diagnosed with gender dysphoria, Defendants do not identify any problem that needs a new solution. Appropriate treatment for gender dysphoria is both “effective” and “no more specialized or difficult than other sophisticated medical care the military system routinely provides.”

To this, Reyes concluded:

Additionally, and as noted above, Reyes — as she had suggested throughout the hearings — heavily looked into whether the policy was motivated by animus.

Reyes noted in her opinion that the government asserted “that the Court cannot probe ‘government officials’ subjective intentions.’” To that, she wrote, “True, the Court cannot read minds. But it can read.”

Then, she went in:

EO14183 and the Hegseth Policy tag transgender persons as weak, dishonorable, undisciplined, boastful, selfish liars who are mentally and physically unfit to serve. … Defendants refused to answer whether this language evinces animus. … But the Court has no such problem. It finds that the Military Ban’s language evinces the “bare…desire to harm a politically unpopular group.”

Reyes then lays out just how extreme the Trump administration’s anti-trans order here is, comparing it to three other cases throughout U.S. history when the Supreme Court struck down policies based on a finding of animus:

Reyes, as she had done in hearings, also noted the many other anti-trans actions of the administration as providing context for her conclusion that “Plaintiffs are likely to prevail on their claim that the Military Ban is driven exclusively by animus.”

With that, and an easy finding that — failing an injunction — the plaintiffs would suffer irreparable harm, Reyes issued her preliminary injunction.

The Trump administration is certainly expected to appeal, but Reyes’s opinion — and her extensive hearings requiring the government to explain its actions — are essential markers in this moment that the anti-trans attack of the Trump administration will not go unchallenged by the courts.

![ORDER For the reasons set forth in the accompanying Memorandum Opinion, the Court hereby: GRANTS Plaintiffs’ [72] Renewed Application for Preliminary Injunction; it further ORDERS that Defendants Peter B. Hegseth, in his official capacity as Secretary of Defense; the United States Department of the Army; Daniel P. Driscoll in his official capacity as Secretary of the Army; the United States Department of the Navy; Terence G. Emmert in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the Navy; the United States Department of the Air Force; Gary A. Ashworth in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the Air Force; the Defense Health Agency; Telita Crosland in her official capacity as Director of the Defense Health Agency, are preliminarily enjoined, pending further order of this Court, from implementing Executive Order No. 14183; as well as “Additional Guidance on Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness,” Dkt. 63-1; and any other memorandums, guidance, policies, or actions issued pursuant to Executive Order 14183 or the Additional Guidance on Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness. ORDER For the reasons set forth in the accompanying Memorandum Opinion, the Court hereby: GRANTS Plaintiffs’ [72] Renewed Application for Preliminary Injunction; it further ORDERS that Defendants Peter B. Hegseth, in his official capacity as Secretary of Defense; the United States Department of the Army; Daniel P. Driscoll in his official capacity as Secretary of the Army; the United States Department of the Navy; Terence G. Emmert in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the Navy; the United States Department of the Air Force; Gary A. Ashworth in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of the Air Force; the Defense Health Agency; Telita Crosland in her official capacity as Director of the Defense Health Agency, are preliminarily enjoined, pending further order of this Court, from implementing Executive Order No. 14183; as well as “Additional Guidance on Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness,” Dkt. 63-1; and any other memorandums, guidance, policies, or actions issued pursuant to Executive Order 14183 or the Additional Guidance on Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0P5Q!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fface47c0-0446-4df6-ab2c-330387b6e1de_1314x1018.png)

I thought she did an exceptionally good job setting this up to withstand a challenge in the court of appeals and on to SCOTUS.

pretty sure that "Dripping with Animus" is Trump's new legal name.