The Supreme Court won't let a racist jury stop a death sentence

“I think we should stay with our Blood Line,” a juror who later sentenced Andre Thomas to death told lawyers before trial. The conservatives let the Texas death sentence stand. And: More from SCOTUS.

All six Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices on Tuesday refused even to hear Andre Thomas’s case out of Texas. Thomas had been challenging the death sentence he faces because it was tainted by some of the most base racist arguments.

The Supreme Court, in the past, has taken steps — even in recent years — to remove outright racism from criminal trials and juries, but Tuesday was different.

“Thomas was convicted and sentenced to death by a jury that included three jurors who expressed bias against him,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor explained, dissenting to the court’s decision on Tuesday, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, in a case where bias against interracial marriage, relationships, and procreation was front and center. “Far from avoiding these incendiary topics, the State fanned the flames in urging the jury to sentence Thomas to death.”

Thomas, a Black man with schizophrenia, has been sentenced to death. He was convicted of murdering his estranged wife, who was white, and her two children, one of whom was also his, during a psychotic episode.

An all-white jury heard his case. Although that could be troubling enough on its own, this was far worse. The jury included three jurors and an alternate who specifically said they disapproved of interracial marriage and procreation.

The trial, lest you think this is a case from long in the past, took place in 2005.

One juror marked on his jury questionnaire that he “vigorously oppose[d]” interracial marriage. One of those who marked that they opposed interracial marriage added that they did so because, they wrote on the questionnaire, “I think we should stay with our Blood Line.”

Thomas’s lawyers — again, this is 2005 — only asked the prospective juror who said he “vigorously” opposed interracial marriage any specific follow-up questions about racial bias and ultimately did not challenge any of these four people opposed to interracial marriage and procreation from being seated on the jury as jurors or, in the one case, an alternate.

The murders were brutal, and Thomas himself had confessed to the crimes. His only defense in the guilt phase of the trial was an insanity defense (the treatment of which was, yes, another concerning aspect of his case not at issue before the Supreme Court). He was nonetheless convicted, which then led to sentencing.

After having had women testify — four white women and one Latina woman, according to Thomas’s petition to the Supreme Court — about his pursuit of and relationships with them, the prosecutor specifically noted the possibility of parole for Thomas if the jury didn’t sentence him to death. The prosecutor asked the jurors:

Are you going to take the risk about him asking your daughter out, or your granddaughter out? After watching the string of girls that came up here and apparently could talk him into—that he could talk into being with him, are you going to take that chance?

The jury, in effect, responded no, sentencing Thomas to death.

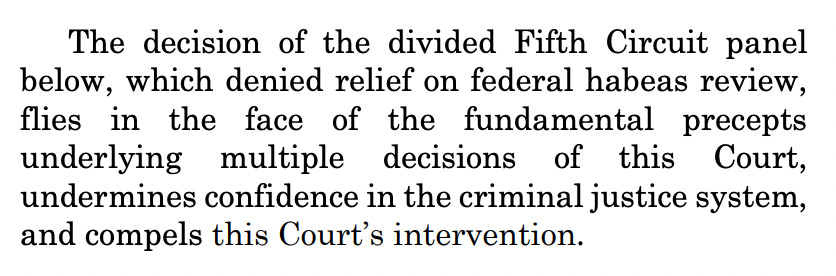

Texas courts and the federal district court allowed the sentence to stand. When the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit agreed, rejecting Thomas’s habeas claims that he was denied an impartial jury and had received ineffective assistance of counsel, the dissenting judge called the decision to put the three people on the jury “objectively unreasonable, contradicting the clearly established Supreme Court … caselaw.”

The juror who “vigorously” opposed interracial marriage “admitted to racial animus—condemned by the unanimous Supreme Court one half century ago in Loving v. Virginia as ‘odious,’ ‘invidious’ and ‘repugnant’—here against the exact interracial circumstance of the offense Thomas was sentenced to death for,” Judge Stephen Higginson wrote. “The law rightly condemned this repugnancy when enacted as law by lawmakers, just as it must condemn it when we ask citizens to join us as judges.”

Higginson, an Obama appointee, was in the minority, though. Judge Leslie Southwick, a George W. Bush appointee who had been a Mississippi appeals court judge and was born in 1950, wrote the Fifth Circuit’s majority opinion rejecting Thomas’s challenge. He was joined by Judge Edith Jones, a Reagan appointee born a year earlier.

The majority held that state court decisions that Thomas had not had an impermissibly biased jury and had not received ineffective assistance of counsel were not unreasonable decisions and, under federal law, deserved deference. In other words, even if they weren’t how the federal appellate judges would have ruled on those issues, there were reasons given for them, and so the federal courts would defer to the state court decisions.

Of course, and as Higginson dissented, this was avoidance: “I would apply clearly established Supreme Court law to forbid persons from being privileged to participate in the judicial process to make life or death judgment about brutal murders involving interracial marriage and offspring those jurors openly confirm they have racial bias against.”

Lawyers for Thomas took their plea to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to take up the case.

“[T]his Court has unequivocally held that the relevant inquiry in a juror bias case is whether all 12 jurors are impartial prior to being seated,” Thomas’s lawyers wrote as to the bias claim — not whether the result itself can be shown to be racially biased.

Regarding the ineffective assistance of counsel claim, they wrote, “Just as any reasonable attorney would have recognized the need to protect a capital defendant from racially biased expert testimony influencing the proceedings, … any reasonable attorney would have recognized the need to protect a Black client from racially biased persons serving on the jury.”

On Tuesday, six of the nine refused to hear the case — although the six Republican appointees who refused gave no reasoning for their decision keeping Thomas on death row.

The Democratic appointees, however, did speak up.

“Thomas’ conviction and death sentence clearly violate the constitutional right to the effective assistance of counsel,” Sotomayor wrote, joined by Kagan and Jackson. “The errors in this case render Thomas’ death sentence not only unreliable, but unconstitutional.”

The three votes, however, weren’t enough.

With today’s court, Texas successfully protected Andre Thomas’s death sentence.

WHAT ELSE: There was a lot more from the Supreme Court on Tuesday, although the justices didn’t announce they were taking any new cases.

The Supreme Court’s decision not to hear a case over the tapes Judge Vaughn Walker made of the trial over California’s Proposition 8 marriage ban means the tapes can now be made public.

The justices also turned down Dylann Roof’s death penalty appeal.

In oral arguments on Tuesday, the justices heard Rodney Reed’s case out of Texas — which focused on procedural rules and state-federal considerations in Reed’s attempt at securing DNA testing. Reed’s execution had been halted by a Texas court in 2019, when bipartisan outcry over the cause brought his scheduled execution into the spotlight.

FINALLY: Big news from Josh!

![Adjudicating this horrific crime would challenge any juror, but it is constitutionally prohibited for a racially biased juror who "vigorously oppose[s]" (Juror Ulmer) (or "oppose[s]"—Jurors Copeland and Armstrong) "people of different racial backgrounds marrying and/or having children." Adjudicating this horrific crime would challenge any juror, but it is constitutionally prohibited for a racially biased juror who "vigorously oppose[s]" (Juror Ulmer) (or "oppose[s]"—Jurors Copeland and Armstrong) "people of different racial backgrounds marrying and/or having children."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IRmq!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3015f76-b293-43c7-87f9-fac2ca8bc97a_832x372.png)

Our Supreme Court is irretrievably broken.