The education of Judge Gregory Katsas

The latest in the CFPB litigation tells an important story of what one Trump appointee has seen over the past month. And, for paid subscribers: Closing my tabs.

For Judge Gregory Katsas, a Trump appointee from the president’s first term, a month on the motions panel at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit appears to have taught him an important lesson about President Donald Trump’s second term.

The Trump administration is not a collaborative force seeking to work with the other branches to carry out the mission of governing the nation. The Trump administration, as we have seen countless times in Trump’s first 100 days, is a destructive force seeking to exploit the weaknesses of the co-equal branches — and other institutions — to carry out their mission of taking over the nation on Trump’s behalf.

Katsas, who also worked in the White House Counsel’s Office during the first Trump administration, is learning that lesson in as direct a way as an appellate judge can do.

The D.C. Circuit’s “special panel”

On the D.C. Circuit, a “special panel” is appointed internally per court rules to address motions and other emergency matters before a new appeal is submitted to a merits panel. The circuit’s “practice and internal procedures” handbook tells us:

The special panel consists of judges who are assigned on a rotational basis throughout the year to consider and decide motions … and emergency matters …. The special panel members also are engaged in their regular merits sittings while they serve on the special panel. … The Court does not publish or disclose in advance the names of the judges on the special panel, nor does it notify counsel or the public of the date on which a particular motion will be considered. The panel does not hear oral argument on motions, except, very rarely, in emergency matters or for extraordinary cause.

The “special panel,” or motions panel, sits for roughly a month, and it appears to turn over at the beginning of each month. The D.C. Circuit currently has seven Democratic appointees and four Republican appointees — three of whom were appointed to the court by Trump.

All of which brings us to this month’s panel, which included two of the three Trump appointees — Katsas and Judge Neomi Rao. Judge Cornelia Pillard, an Obama appointee, is the third judge on the panel.

As with all court rulings, majority rules, so this was about as good of a panel as Trump could expect (especially given that the other two Republican appointees were on the March special panel). We have seen that play out, both in the Trump administration’s eagerness to go to the panel once we knew who it was and, to an extent, with their rulings.

But, as I began this post by saying, this month has a story to tell.

On April 2, in what, to my knowledge, was the first order of the new motions panel, Katsas, Pillard, and Rao set a briefing schedule — including the “very rare” oral argument — on the Justice Department’s request for a stay of U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson’s March 28 preliminary injunction blocking the Trump administration’s efforts to destroy the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The order, along with the underlying litigation, relates both to the CFPB leadership and the leadership of the non-department Department of Government Efficiency.

The next day, the panel granted a partial administrative stay, while it considered the request for a stay pending appeal, that left certain previously agreed upon restrictions in effect during that time:

On April 9, the panel heard arguments over the injunction, which stated:

At the arguments, Katsas asked the Deputy Assistant Attorney General Eric McArthur how he could know whether 300 CFPB employees — tentatively to be retained after mass-firings under an initial plan — could carry out the agency’s required statutory duties. Later, Katsas also asked how the court could craft an order that would allow RIFs that would not “endanger the agency.”

Two days later, on April 11 — a Friday — the panel granted a partial stay of Jackson’s injunction, which left much of the order in effect, but — important to our discussion — limited paragraph 3 blocking the agency from carrying out any reduction-in-force, or RIF, to allow a RIF but requiring a “particularized assessment” determining that the employees being fired were “unnecessary to the performance of defendants’ statutory duties”:

On April 17, more than 1,400 CFPB employees received RIF notices. Only a little more than 200 employees were to be retained. That evening, the plaintiffs in this lawsuit went back to Jackson:

On Friday, April 18, Jackson held a hearing and temporarily blocked the firings — and planned CFPB systems access shut-off at 6 p.m. April 18 for those employees — until she could hold a hearing on whether the RIFs violated the preliminary injunction, as amended by the D.C. Circuit’s order. In the interim, she also ordered CFPB to turn over certain discovery about the RIFs to the plaintiffs.

That weekend, DOJ went back to the D.C. Circuit, with an emergency motion asking the panel “to enforce or clarify” the partial stay issued by the D.C. Circuit.

This time, the panel waited until Monday, April 21, to even order a response — and then set a briefing schedule that went through April 23, which started moving into the time when the CFPB would be needing to turn over evidence.

Then, despite days of intense briefing and evidence production in the district court — and a hearing before Jackson scheduled for Monday — the week came to a close with nothing from the D.C. Circuit.

Over the weekend, at the request of the parties, Jackson moved the hearing to Tuesday and Wednesday. Late on Sunday, April 27, the plaintiffs challenged the withholding of documents by the government under a claim of privilege. On Monday, DOJ alerted the D.C. Circuit of this before filing its response.

Then, on Monday afternoon, we got an order from the D.C. Circuit.

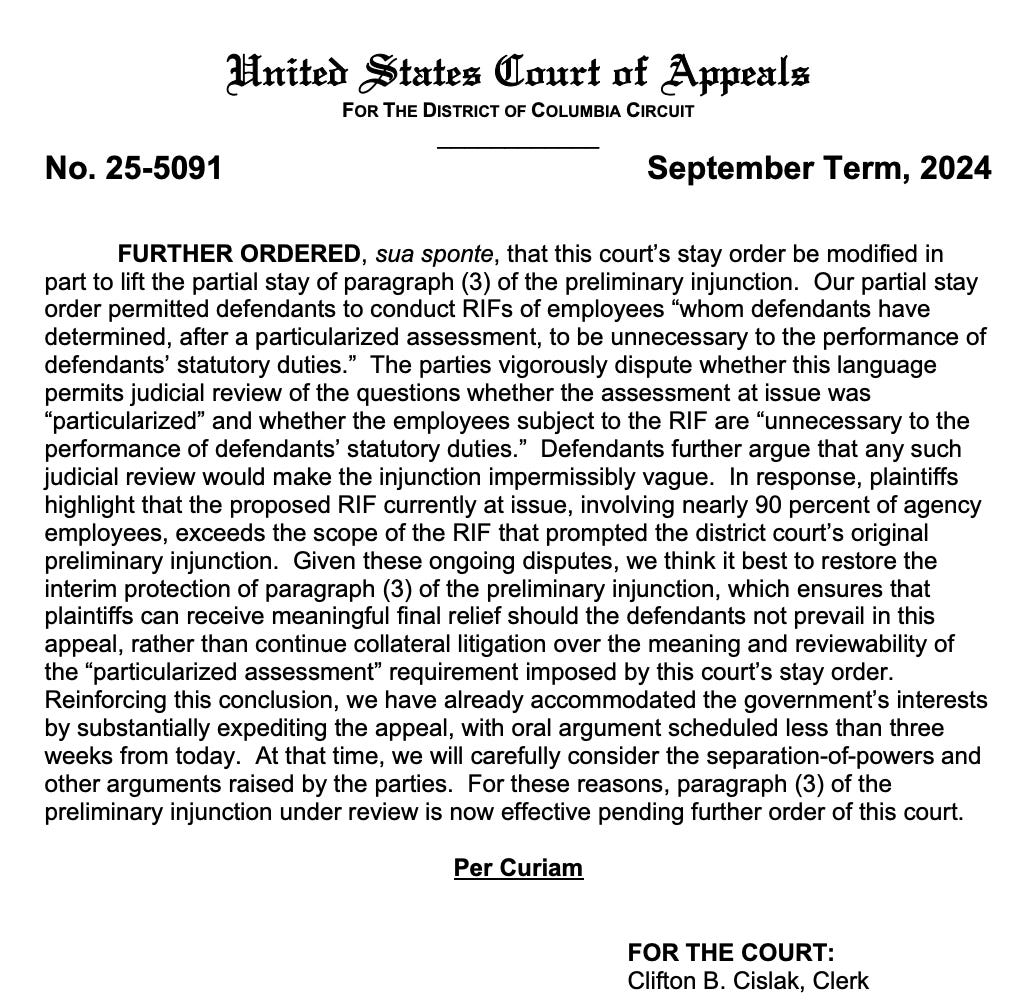

There had been important movement. In a key part, Pillard and Katsas modified the partial stay they had issued just 17 days earlier and put paragraph 3 of Jackson’s injunction back into effect.

Rao dissented, stating that the panel “bars the political leadership of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) from reducing its workforce in accordance with President Trump’s directives.”

Criticizing the plaintiffs for even going back to court after the RIF was issued rather than “wait[ing] to see if any harm materialized,“ Rao wrote that she would have found that even Jackson’s temporary pause on the RIF to give her time to decide if it was allowed under the injunction was “an abuse of discretion.”

In short, Rao would have let the 1,400-employee RIF go into effect.

But not Katsas.

Instead, as his month on the “special panel” nears its close, Katsas — Trump’s former White House lawyer — joined with Pillard to tell the agency that it had to stop with any RIFs at all until the D.C. Circuit can hear the appeal of the injunction in May.

Of course, this is not some sea-change, and Katsas is likely still to side with the administration on many matters.

But, over the course of the month, a cautionary tale has played out in front of him — and he responded by stepping in to assert the rule of law.

Closing my tabs

This Monday, these are the tabs I am closing: