Texas's anti-drag law is unconstitutional, federal judge rules, permanently blocking enforcement

The ruling from a Reagan appointee leaves Matthew Kacsmaryk's ruling defending West Texas A&M's drag ban as an outlier in drag cases. An appeal is expected.

On Tuesday, a federal judge in Texas struck down S.B. 12, the state’s new anti-drag law that includes both civil and criminal penalties, declaring it to be unconstitutional and barring state officials from enforcing it.

“Not all people will like or condone certain performances. This is no different than a person's opinion on certain comedy or genres of music, but that alone does not strip First Amendment protection. However, in addition to the pure entertainment value there are often political, social, and cultural messages involved in drag performances which strengthen the Plaintiffs position“ that drag performances are expressive conduct subject to First Amendment protections, U.S. District Judge David Hittner wrote in his 56-page ruling.

Specifically distinguishing his decision that the state law is unconstitutional from last week’s ruling from U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk defending the West Texas A&M University president’s decision barring drag shows from campus, Hittner referred to Kacsmaryk’s ruling as “one of the only federal cases where drag shows did not receive First Amendment protection.”

As part of the lawsuit over the law that was passed this spring, Hittner, an 84-year-old Reagan appointee to the federal bench, issued a temporary restraining order on Aug. 31 halting enforcement of the law before it was to go into effect on Sept. 1. A two-day trial followed, leading to Tuesday’s ruling.

Ultimately, Hittner found that the law is unconstitutional on all of the First Amendment grounds argued by the plaintiffs, drag performers and businesses that host or employ drag performers. The law is an unconstitutional content-based and viewpoint-based restriction, unconstitutionally overbroad, void due to its unconstitutional vagueness, and an unconstitutional prior restraint, Hittner ruled.

Although the extensive ruling — laying out his findings of fact and conclusions of law — followed a trial with witness testimony, the next step, assuming Texas appeals, is the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. On Monday, that court issued an administrative stay in Texas’s appeal of a First Amendment challenge to the state’s new book-ban regime, allowing that law to at least temporarily go into effect. As such, anyone considering the stability of Tuesday’s ruling from Hittner should bear that in mind.

What Hittner decided

Although the text of the Texas statute is less direct than some of the other anti-drag laws we’ve seen, Hittner noted the drag focus of lawmakers and elected officials: “[T]he same day he signed S.B. 12 into law, Governor [Greg] Abbott tweeted the following: ‘Texas Governor Signs Law Banning Drag Performances in Public. That’s Right.’”

The law itself has three main provisions, as Hittner detailed:

Although some of those elements caused issues for the law, it was, as with most of these laws, the definition of “sexual oriented performances” — contained within Section Three but applicable to the whole law — that led to most of the problems.

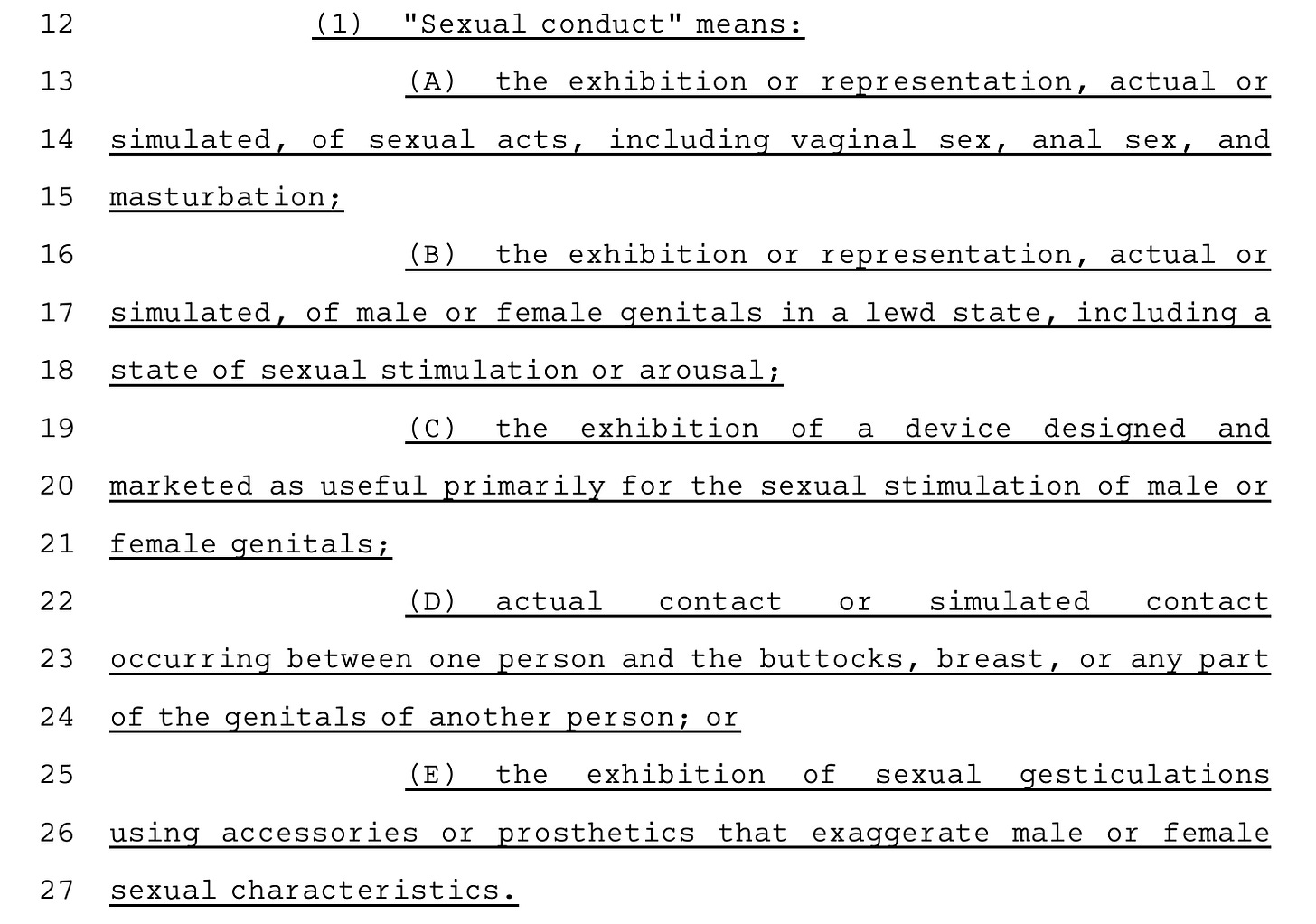

The law defines “sexually oriented performances” as such:

What is sexual conduct, you ask? The law defines that in the section that comes closest to directly referencing drag (in subpart E):

Finally, the law purports to limit the covered “sexually oriented performances” subject to criminal penalty as follows:

After detailing the testimony established by the plaintiffs at trial, regarding their fears that their performances or that performances that take place as a part of their business or at their venues could or would be illegal under the law, Hittner went on to his legal conclusions.

Hittner quickly found that the named defendants, including Attorney General Ken Paxton, “all have some role to play in enforcing S.B. 12” and are appropriate parties. He also found that the plaintiffs have standing to bring the case because they showed “that their activities are ‘arguably proscribed’ by the statute,” citing U.S. Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit precedent on the matter.

Then, in an important element of his ruling, Hittner found that the law isn’t severable — unconstitutional parts couldn’t be removed from constitutional parts, if there are any — because “S.B. 12 relies on the definitions and terms in Section Three throughout the bill.”

With all of that cleared out of the way, Hittner got to the merits, starting with the question of whether drag receives First Amendment protection as expressive conduct.

“[A] survey of court decisions related to the issue of drag shows reveals little divergence from the opinion that drag performances are expressive content that is afforded First Amendment protection,“ Hittner wrote, going on to detail his strong agreement. “Drag shows express a litany of emotions and purposes, from humor and pure entertainment to social commentary on gender roles. There is no doubt that at the bare minimum these performances are meant to be a form of art that is meant to entertain, alone this would warrant some level of First Amendment protection.”

Hittner then distinguished Kacsmaryk’s decision, as discussed above.

The five ways the law is unconstitutional

Having found that drag performances are subject to First Amendment protections, he went on to each of the claims:

Content-based discrimination: “The law targets conduct deemed to be ‘sexual oriented.’ That alone suggests a content-based restriction,” Hittner wrote, noting that “S.B. 12 targets the content of speech, i.e., ‘sexual oriented performances,’ some of which do not rise to the definition of obscenity. Accordingly, S.B. 12 is a content-based restriction and is subject to strict scrutiny.”

Under strict scrutiny, a law or policy must advance a “compelling state interest” and do so in a “narrowly tailored” way.

“[T]he pertinent question is whether S.B. 12 as written, is narrowly tailored to promote the state's compelling interest of protecting children,” Hittner wrote. “The answer is no for a multitude of reasons.”

Hittner detailed three reasons, all raised in other cases as well. First, he noted that, while the state’s use of “prurient interest” evokes the Supreme Court’s obscenity test (known as the Miller test), the law “excludes the other relevant prongs of the Miller analysis.“ Because of this, the law covers conduct that would not be considered obscenity. Second, the law doesn’t distinguish based on the age of the child in question, which makes the “prurient interest” assessment difficult. Finally, the law contains no affirmative defenses, even for a parent choosing to allow their child to watch a performance that, as Hittner wrote, “does not rise to the definition of obscenity.”

Viewpoint-based discrimination: “While the term ‘drag show’ is not mentioned anywhere in the text of S.B. 12, there is language to suggest targeting of drag shows,” he wrote. “In addition, the legislative history shows legislative intent to target drag shows.”

Overbreadth: Again noting the only-partial inclusion of the Miller test in the standard laid out in the law, Hittner noted, “S.B. 12 has no requirement that the work be patently offensive or a carve out for work that is comical or has serious literary, artistic, political, and scientific value.”

Ultimately, Hittner concluded, “The Court sees no way to read the provisions of S.B. 12 without concluding that a large amount of constitutionally protected conduct can and will be wrapped up in the enforcement of S.B. 12.”

Void for vagueness: Addressing the Miller test questions, other undefined terms, and the difficulty in assessing whether certain performances would be covered or not, Hittner concluded that “the vague language and seeming omission of clear guidance makes S.B. 12 vague.”

Prior restraint: Finally, Hittner addressed the plaintiffs’ claims that the law created an unconstitutional prior restraint. The defendants did not help themselves here.

Nonetheless, he made do, quickly concluding that the authority granted to local governments under Section Two “to pass ordinances to stop conduct that as discussed above is protected by the First Amendment is a prior restraint on speech.”

With that, Hittner quickly ruled that the reminder of the injunction factors were easily met and concluded that the court:

There is no formal word yet whether Texas or the other defendants are appealing, but it does seem inevitable.

Typo: "Nonetheless, he made do, quickly concluding that the authority granted to local governments under Suction Two"

Any guess on how many cases will be added to this terms SCOTUS docket as a result of 5th circuit rulings? Seems like at least 4 additions might be possible.