Supreme Court, 9-0, says Colorado can't kick Trump off ballot

Underlying the unanimous ruling, a 5-4 dispute about the majority limiting federal power to enforce the 14th Amendment's "insurrection" disqualification clause.

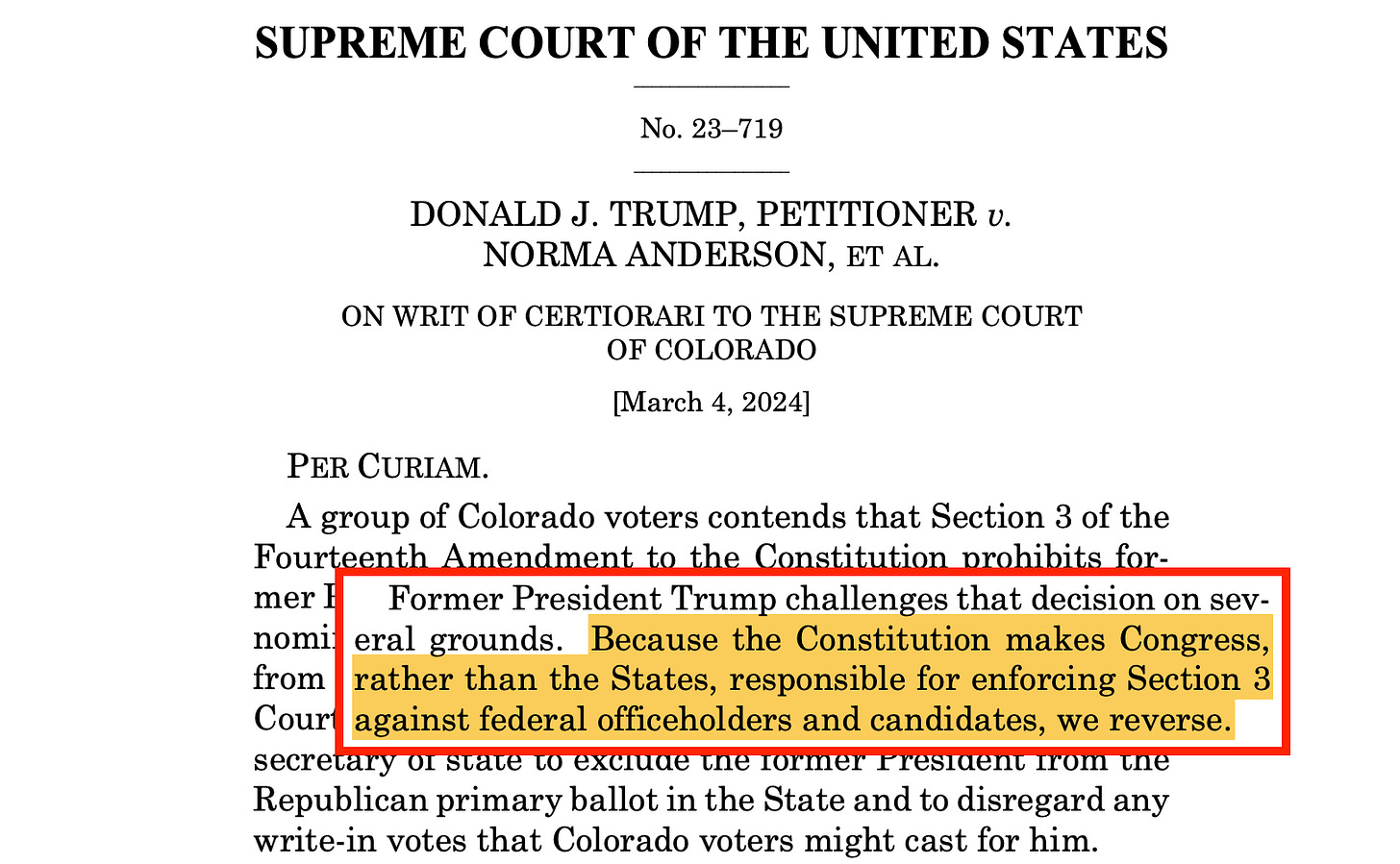

Donald Trump will remain on the ballot in Colorado’s Republican primary on Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously on Monday, reversing the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to the contrary.

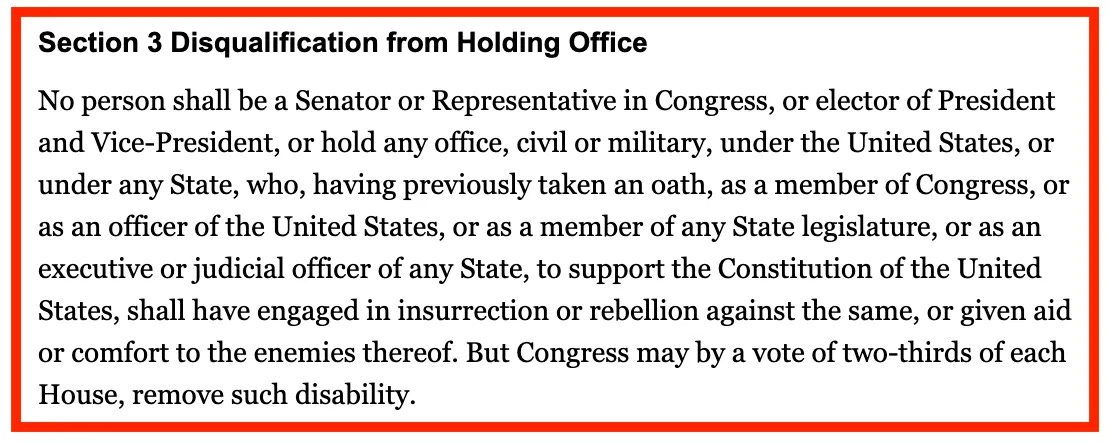

In December 2023, the Colorado court had ruled that Trump could not appear on the ballot because he had engaged in insurrection in connection with his actions related to January 6, 2021, disqualifying him from being president under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment and barring him from appearing on the Colorado primary ballot under state law.

That decision was wrong, the justices held on Monday.

A state cannot act to remove a presidential candidate from the ballot under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, all nine justices of the Supreme Court held in a brief, 20-page decision issued less than a month after the justices heard arguments in Trump’s appeal of the state court’s ruling.

The final judgment in the case was expected, given the Feb. 8 oral arguments, but, below the surface of that unanimous ruling, however, there was a 5-4 dispute about what else the court should have done in the course of resolving the case — prompting a “protest” from the three Democratic appointees.

The majority made a half-hearted attempt to hide the dispute by labeling their opinion a “per curiam” decision, meaning “for the court,” as the majority did in 2000’s Bush v. Gore decision — but both of the other opinions on Monday referred to the “per curiam” opinion as “the majority” opinion that it is.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson highlighted the dispute in a joint opinion concurring only in the judgment, meaning they agreed with the ultimate ruling reversing the Colorado Supreme Court but did not join the majority’s reasoning.

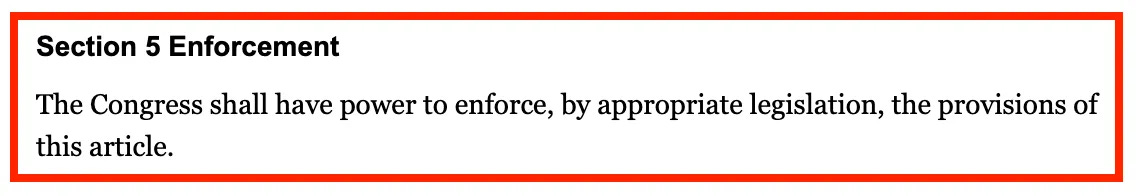

“In a case involving no federal action whatsoever, the Court opines on how federal enforcement of Section 3 must proceed,” the trio wrote.

In the majority opinion — representing the decision of Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Sam Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh — the men wrote into law limits not just on whether states can enforce Section 3 against “federal officeholders and candidates” but also how the federal government can do so.

“The Constitution empowers Congress to prescribe how those determinations [of who is subject to Section 3] should be made. The relevant provision is Section 5, which enables Congress, subject of course to judicial review, to pass ‘appropriate legislation’ to ‘enforce’ the Fourteenth Amendment,” the majority held — setting forth a new national constitutional rule limiting Section 3 enforcement more than 150 years after its ratification.

“Congress’s Section 5 power is critical when it comes to Section 3,” the majority concludes, citing one lawmaker’s floor speech for support — that the Democratic appointees note in their opinion was selectively quoted by the majority.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, writing for herself concurring in part and in the judgment, similarly disagreed with the majority’s approach but stated a belief that “writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.”

Her writing expressed, at least, a strong concern about the instability of this moment. “For present purposes, our differences are far less important than our unanimity: All nine Justices agree on the outcome of this case,” she wrote, almost pleading: “That is the message Americans should take home.”

Despite that, even she acknowledged the problem. Because this case was about Colorado’s actions, Barrett wrote, “It does not require us to address the complicated question whether federal legislation is the exclusive vehicle through which Section 3 can be enforced. The majority’s choice of a different path leaves the remaining Justices with a choice of how to respond.”

Rather than criticizing the majority, however, Barrett then appeared to take aim at the Democratic appointees, writing, “In my judgment, this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency.”

To what stridency is Barrett referring?

Presumably the Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson statement that, “By resolving these and other questions, the majority attempts to insulate all alleged insurrectionists from future challenges to their holding federal office.”

It is a fact that, absent congressional action — which we all know is not happening in the current Congress — the majority’s decision effectively nullifies Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment for now outside of federal criminal prosecution and conviction for “rebellion or insurrection.”

That is significant insulation.

Barrett clearly understands that; she just masked it by calling it “a different path.”

While the majority used its votes to do so and Barrett would let that go quietly, the trio of Democratic appointees called it out:

Now that we have the majority’s ruling, there likely will be criticism of the challengers’ approach to this matter in the days to come — if it isn’t already happening — but I think it has been an important endeavor both to raise these issues and force the court to confront it.

January 6 happened, Trump was the animating and animated force behind it, and now he is asking to be president again.

It would have been irresponsible not to raise these questions.

![Section 3 serves an important, though rarely needed, role in our democracy. The American people have the power to vote for and elect candidates for national office, and that is a great and glorious thing. The men who drafted and rati- fied the Fourteenth Amendment, however, had witnessed an “insurrection [and] rebellion” to defend slavery. §3. They wanted to ensure that those who had participated in that insurrection, and in possible future insurrections, could not return to prominent roles. Today, the majority goes beyond the necessities of this case to limit how Section 3 can bar an oathbreaking insurrectionist from becoming President. Although we agree that Colorado cannot enforce Section 3, we protest the majority’s effort to use this case to define the limits of federal enforcement of that provision. Because we would decide only the issue before us, we concur only in the judgment. Section 3 serves an important, though rarely needed, role in our democracy. The American people have the power to vote for and elect candidates for national office, and that is a great and glorious thing. The men who drafted and rati- fied the Fourteenth Amendment, however, had witnessed an “insurrection [and] rebellion” to defend slavery. §3. They wanted to ensure that those who had participated in that insurrection, and in possible future insurrections, could not return to prominent roles. Today, the majority goes beyond the necessities of this case to limit how Section 3 can bar an oathbreaking insurrectionist from becoming President. Although we agree that Colorado cannot enforce Section 3, we protest the majority’s effort to use this case to define the limits of federal enforcement of that provision. Because we would decide only the issue before us, we concur only in the judgment.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!sIP4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fea66949e-6236-4c65-88c6-4fed00edbc71_1086x758.png)

An excellent post, thank you. This morning I also read a post by Steve Vladeck (Substack: One First) which asked the question: "What does this Court believe its role to be?" He questions their consistency in the rulings they make. I get the impression that the majority are not interpreting law, but writing law to reflect their personal beliefs, which should not be their function as a separate branch of the government.

The 14th Amendment doesn't specify that a state cannot refuse to put a candidate on the ballot if they have violated this Amendment, but that it is only the Federal Government that can do so. If Colorado properly by their state constitution ruled that Mr. Trump is guilty of insurrection, then it appears that they should be able to exclude him from their ballot. If the Federal Congress disagrees with that state ruling, then the 14th Amendment has the provision that Congress can with a 2/3rd majority in each house remove this "disability".

Yes, it would certainly be chaos if some states included Mr. Trump on their ballots & some excluded him, but Congress could fix that, could they not? I get the impression that this possible ensuing chaos is the reason for the ruling, but the Court certainly didn't care about chaos when they overturned a woman's right to chose.

Well, arguments before the Court back in February focused on (1), the ability of one state to decide the national candidacy of a major party's leading figure, and (2), the "need" for federal enforcement legislation per §5. Certainly easy enough to get 5/9 on those two questions, and the 3 concurring Justices weren't about to roil a manufactured "consensus". At least Sotomayor et al raised the "insurrection" question, notably ducked in the PC decision.

As for Justice Coney Barrett, the phrase "lowering the national temperature" was questionable, as it unnecessarily highlighted the *political* aspect of the 9-0 decision, and seemingly tried to excuse quite frankly the inexcusable, i.e., an insurrectionist left on the ballot .