On Wednesday's SCOTUS trans care case — and some lessons from the past

Tennessee's anti-trans ban on minors' medical care is at SCOTUS. It's already been a long and winding path, and that will continue, but we will keep forging ahead.

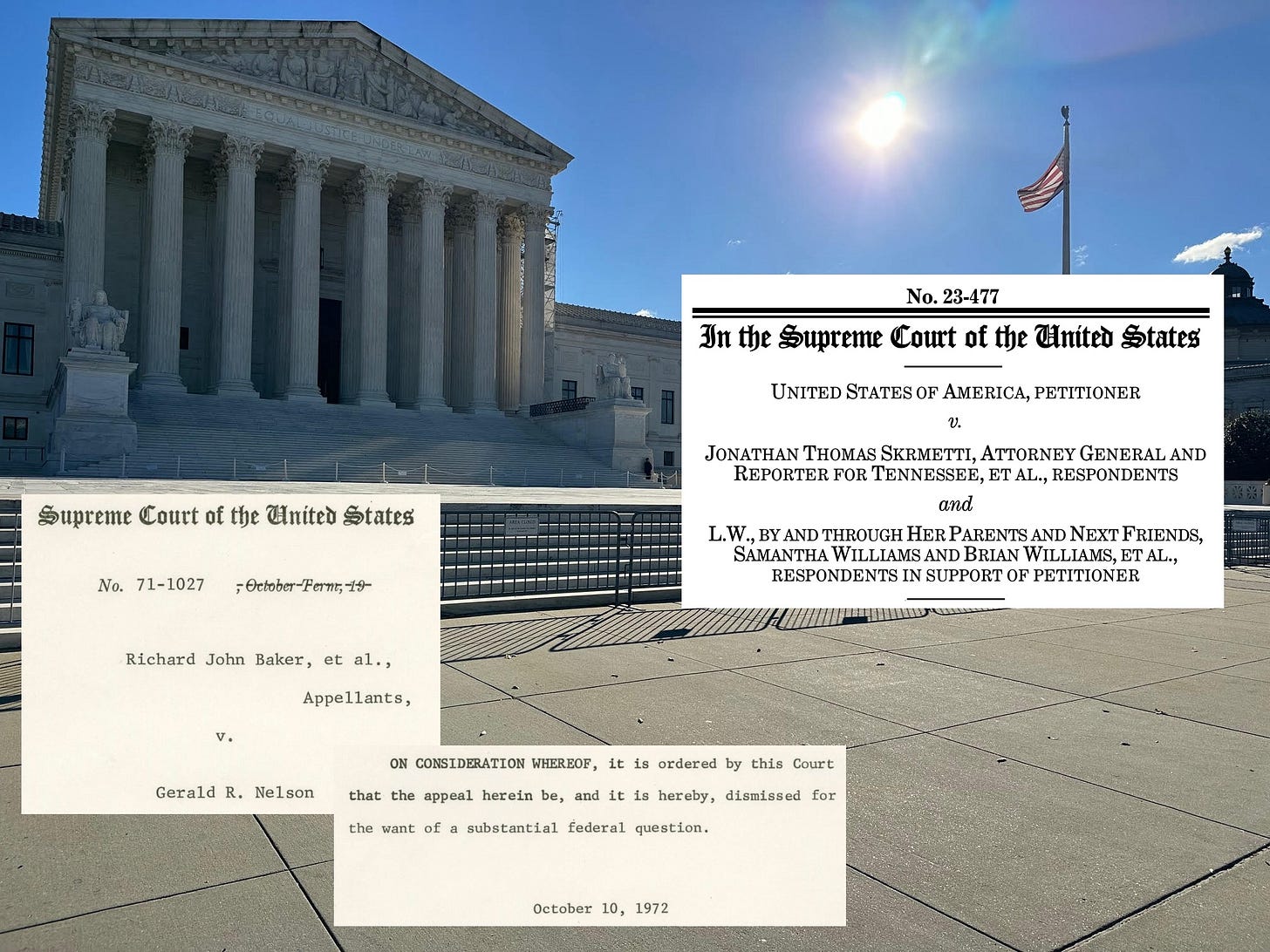

On Wednesday, December 4, the U.S. Supreme Court will be holding oral arguments in United States v. Skrmetti, the case over Tennessee’s ban on puberty blockers and hormone therapy for treatment of gender dysphoria in transgender minors.

I will have much more in the coming days surrounding the arguments, including coverage from the Supreme Court — I’ll be in the courtroom for arguments — on Wednesday.

I wanted to start this coming week, though, with a bit of a historical perspective — contextualizing this moment.

These are my prepared remarks for the keynote address I gave at the “Skrmetti and the Broader Environment for LGBTQ Rights” conference that took place on November 21 and was organized by the Richard C. Failla LGBTQ Commission of the New York Courts and the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law.

In April 2021, Republican Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson vetoed a bill that would have made the state the first in the nation to ban transgender kids from obtaining the medical care that they, their parents, and their doctors decided they needed.

Less than four years later, twenty-four states — including Arkansas — have such bans. If you include bans on surgical care alone, the number jumps to 26.

Now, in less than two weeks, the Supreme Court is set to hear arguments over whether the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws protects against states passing such bans.

How did we get here? What happened? What comes next?

Before we get into all of that: Why am I here?

I have been involved with the national LGBTQ political and legal world for nearly 30 years, from being in D.C. during the time the Defense of Marriage Act was signed into law by Bill Clinton to being in law school when the Lawrence v. Texas decision overturning sodomy laws came down and when the first marriages in Massachusetts took place to being an Ohio voter when a marriage ban amendment passed in 2004 to reporting on the end of “don’t ask, don’t tell” and marriage bans from Washington, D.C., at Metro Weekly and then BuzzFeed News to covering the heightened anti-trans legislative and cultural environment here today at Law Dork.

We’ll revisit some of that, but that’s the short story of how I got here.

Now, how did we get here?

Efforts to pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act and, later, Equality Act, never got across the finish line. They should have, and we might not have found ourselves in this position had a trans-inclusive ENDA or the Equality Act ever have been passed into law.

But, they weren’t, so in 2012, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued a decision holding that Mia Macy’s claim of anti-transgender discrimination was a type of sex discrimination barred by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — news that I broke at Metro Weekly. A few years later, the EEOC said the same reasoning applied to sexual orientation discrimination.

At the same time, in varying contexts, federal courts — including the Sixth Circuit and Eleventh Circuit — had begun recognizing how anti-transgender discrimination could be a type of sex discrimination as well.

A few years after that, in 2020, the Supreme Court agreed in Bostock v. Clayton County. The 6-3 decision by Justice Neil Gorsuch was then used by the Biden administration to apply the reasoning of Bostock to other sex discrimination bans.

And yet, it was in that moment when far-right organizations — often the very same people who earlier were fighting to support marriage bans — started pushing anti-trans laws. Sports bans, bathroom bans, and, eventually, medical care bans — among other measures — began being proposed and passed into law.

On April 6, 2021, the Arkansas legislature overrode Hutchinson’s veto and Alabama became the first state to ban medication for transgender minors that remain available to cisgender minors. Alabama followed soon thereafter.

Then, however, and even as more states began considering and passing such legislation, we started to see the strength of the legal past.

U.S. District Judge James Moody, an Obama appointee, blocked the Arkansas law from going into effect. Chase Strangio, a lawyer at the ACLU who is himself transgender, was one of the lawyers arguing for that injunction. The next year, U.S. District Judge Liles Burke, a Trump appointee, did the same with the Alabama law. By the next fall, after an Eighth Circuit panel upheld the injunction against the Arkansas law, the full Eighth Circuit — a court that only has one Democratic appointee — denied the state’s request to rehear the case en banc.

In 2023, as the anti-trans laws multiplied, the pattern held — at first. District court judges appointed by presidents of both parties blocked laws in Florida , Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana. A Georgia law later faced a similar ruling.

All of these cases have revolved around three main claims: On equal protection, the laws are challenged as unconstitutionally discriminating based on sex and based on transgender status. On due process, the laws are challenged as unconstitutionally infringing on parental rights — generally regarding the upbringing of their children, and specifically as to medical decisions. In most of the challenges, at least on the preliminary injunction requests, the district courts found the laws likely fail under all three claims.

Then, however, more appeals courts got involved.

In July 2023, Judges Jeffrey Sutton and Amul Thapar on the Sixth Circuit became the first two federal judges in the nation to allow a ban — two bans — to go into effect during litigation. Both men are notable in their own right: Sutton is a George W. Bush appointee — and my former law school professor (he gave me two As) — who a decade ago upheld the constitutionality of marriage bans before being overturned by the Supreme Court. Thapar is Donald Trump’s first appeals court nominee and was backed strongly but unsuccessfully by Mitch McConnell for a Supreme Court seat later in Trump’s first term.

As Tennessee and Kentucky’s bans went into effect while the appeals court heard the state’s appeal of the district court’s injunctions, a third appeals court, the Eleventh Circuit, weighed in. There, Judge Barbara Lagoa — a Trump appointee who also was on the short-list to be nominated for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat — wrote an extensive opinion allowing Alabama’s ban to go into effect. The three-judge panel there consisted of three Trump appointees.

Then, the Sixth Circuit heard its arguments and, in late September, issued its decision. Sutton wrote the 2-1 decision, which, in relevant part, held that the laws do not not classify based on sex and, as such, are subject only to rational basis review. Thapar joined him, while Judge Helene White — another George W. Bush appointee like Sutton — dissented.

Since then, court rulings have been mixed, with some judges literally copying-and-pasting from Sutton and Lagoa’s opinions — like a judge in Oklahoma did — and others still pushing back — like a judge in Florida did (until the Eleventh Circuit, again, weighed in).

By then, though, it was clear this was going to the Supreme Court.

The Tennessee and Kentucky plaintiffs, as well as the United States, which intervened in the Tennessee case, filed petitions for review at the Supreme Court. The court, however, only granted certiorari of the DOJ’s petition — which is limited to the equal protection claims.

Now, the case has been fully briefed and oral arguments are set for Wednesday, and Strangio will be arguing for the private plaintiffs. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar will be arguing her last high-profile case as S.G. for the United States. Tennessee Solicitor General Matthew Rice, who clerked for Justice Clarence Thomas, will be defending the ban.

Of course, in the meantime, the election has happened and Donald Trump will be returning to office on January 20. Republicans will have control of both chambers of Congress — not just the House — come January 3.

Since the court ended this past term, I’ve been writing about how the court was setting itself — and the nation — up for a contingent moment. The election was that moment, and now we’re heading right on into the “Trump won” direction.

The court will now either be proving me right or wrong about where it’s at. It will be able to give in to its far-right leaning if it wants, with no real federal pushback. Here’s what I wrote about the Trump plan: “Roberts has set up the court to be pliant appeasers of Trump’s planned right-wing authoritarianism. Sure, there will be minor pushback, but if Trump v. Hawaii was what we got out of the court during a first-term Trump administration, imagine what this more extreme court would OK in a second term.”

Now, we will see what happens, in part, on December 4.

The best-case scenario for this moment, I think, would be a quick decision holding that the laws do classify based on sex, and that, as such, they are to be subjected to heightened scrutiny. If that’s the decision, then Sutton (and Thapar) got that wrong, so the Supreme Court could quickly send the case back to the Sixth Circuit to reconsider the law under heightened scrutiny.

Any decision other than that starts to get complicated or worse. Any decision on the application of the proper level of scrutiny to the Tennessee law surely will take longer to reach a decision — with stronger dissents.

If the court takes too long with the case, the Trump administration could try to complicate things by telling the court as soon as Trump takes office that the federal government is changing its position in the case. Although this wouldn’t necessarily mean the court needs to dismiss the case — since the plaintiffs are in the case — it could lead the court to dismiss this petition. At that point, maybe they would grant certiorari on the Tennessee plaintiff’s petition, or just grant certiorari as to their equal protection question. Perhaps at that point, the court could avoid arguments and just seek supplemental briefing or hold arguments this term, but it could send the case to the fall. Regardless, and to return to the bottom line, it would be more complicated.

But, I don’t want to get too deep into that before I pull back to look at the bigger picture.

Although there is little evidence that anti-trans campaigns actually work, the Trump campaign and his allied campaigns put millions of dollars into anti-trans ads this fall. In the fallout from the election, a few Democrats have either directly said that Democrats should pull back in their pro-trans positions or implied it in a “stop focusing on social issues” way. Then, as questions about qualifications of and serious problems with Trump’s nominees have been raised, some members of Congress responded with disingenuous and anti-trans retorts noting that Rachel Levine, the assistant secretary for health in HHS, is in the Biden administration — a statement that is nonsensical unless her trans status itself is suspect.

Finally, there’s Rep. Nancy Mace and her appalling resolution that would block incoming Rep. Sarah McBride from Delaware — who will be the first out trans member of Congress — from using the restroom, as well as the many trans staffers on Capitol Hill. That, of course, led Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene to jump in. And, House Speaker Mike Johnson not only voiced his support for such a bathroom ban, but asserted that it would be so.

As horrifying as some of these developments are, they make the animus clear. Mace and Greene are not engaged in deep concerns about women’s safety. Greene, for example, was almost cartoonishly cruel on the steps of the Capitol when a reporter asked her about Mace’s resolution. At another point, Greene said of McBride, “He’s a biological man pretending to be a woman,” saying that she has “a mental illness.”

It’s appalling hate, and I am sorry that Sarah is going through this — and hope that her new colleagues, and all of us, support her and all of the Hill staffers who are going to get caught up in this. It could get dark.

To the extent I can end on a positive note, here is where I will try and do so. It is the extremists, it is the haters, who always expose themselves for who they are. Then, queer people tell our stories. And, in the meantime, we help each other.

The legal case against these laws are clear. All that Sutton really has is a reliance on democracy, missing its obvious failures and insisting that this is not a matter for the courts. He is wrong about the purpose of our Constitution’s protections today, as he was wrong when he upheld marriage bans a decade ago.

But, it sometimes takes more.

It took more when the Supreme Court dismissed Richard Baker and James McConnell’s marriage case “for want of a substantial federal question” in 1972. It took more when the Supreme Court upheld criminal sodomy laws in 1986.

But, in the years that followed, gay, lesbian, and bisexual people told stories. During the height of the AIDS epidemic in America, we were there for each other. The world changed. The law followed. This could, of course, be its own lecture — and often is — but I think many of us lived through this and, for now, I can skip ahead.

Despite all of the lessons, though, it can at times be hard for me to remember that there sometimes needs to be more than law. The law is so clear to me, but at times we need to tell our stories to show people that their fears — whether based on fear-mongering or ignorance — are just that.

And, regardless of what courts do, we can act — as we saw most recently when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. Women and other pregnant people told their stories, people were there for one another, and other actions — from state courts to the initiative process and beyond — have been taken to reinstate abortion protections.

I often am reminded of a Kentucky case from more than 50 years ago, when Marjorie Jones and Tracy Knight sought a marriage license in Louisville from the County Court Clerk of Jefferson County.

They were denied and sued.

Fifty-one years ago this month, Judge Roy Vance — a commissioner on the Kentucky Court of Appeals — wrote in rejecting their case, “In substance, the relationship proposed by the appellants does not authorize the issuance of a marriage license because what they propose is not a marriage.”

It was. Vance was wrong.

As of the 2020 Census, there were 6,887 married same-sex couples in Kentucky.

The path ahead may be difficult, and it may not be clear, but it is possible.

Thank you for the reminder that it's gotten better in the past after some pretty big setbacks, and we have to keep telling our stories and living.

I don’t pretend to completely comprehend the complicated legal jargon. I continue to read your Substack to educate myself and share what I learn when it comes up in conversation. I wish more people had the time and took the effort to educate themselves on particular cases and the importance of the judicial branch when it comes to our freedoms and the survival of democracy. Thank you Chris for making the seemingly out of reach for the average American more accessible through your Substack articles.