SCOTUS holds off ruling on Trump's Nat'l Guard request, leaving troops blocked from Illinois for now

Court orders briefing about a part of the law the Trump admin is using to federalize National Guard troops. Also in Illinois: Protesters indicted and an attempt to protect Bovino.

The U.S. Supreme Court put off ruling on the Trump administration’s request for an order that would allow President Donald Trump to send National Guard troops into Chicago — likely meaning that troops will be blocked from being deployed in Illinois at least through November 17.

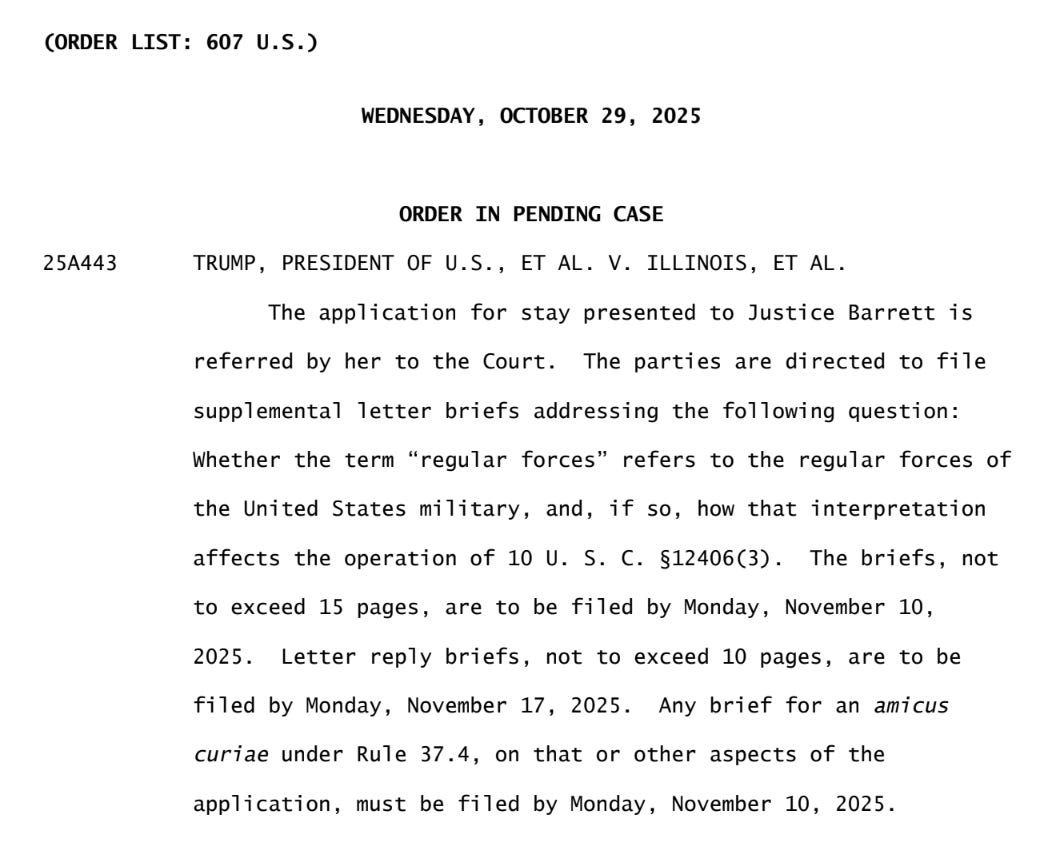

The Supreme Court’s order, issued for the full court, did not rule on the Justice Department’s October 17 requests for an “immediate” administrative stay or for a stay pending appeal of U.S. District Judge April Perry’s temporary restraining order blocking deployment of National Guard troops in Illinois.

Instead, the court called for additional briefing about the meaning of two words — “regular forces” — in the law Trump is relying upon to federalize and deploy the National Guard.

While that legal issue gets complicated, the big news here is that the court has essentially said that it is not planning to issue an order responding to DOJ’s “emergency” request for at least a full month after DOJ filed the request.

Although it is not a ruling, it is, by implication, a pretty clear statement that there is not a majority of the court ready and willing to side with Trump on this issue at this time.

First, the court has not granted DOJ the “immediate” administrative stay of the TRO that it sought. Although the court has not, technically, denied the request, it’s not going to happen. Further, it took more than a week since the matter was fully briefed on October 21 to get Wednesday’s order — seeking more briefing. And, when the court did so, it set a relatively relaxed timeline, ordering supplemental briefing by November 10, with time for replies by November 17.

This means, absent some unexpected order or development, Perry’s TRO — which DOJ agreed will remain in place absent higher court order until final judgment in the case — will remain in effect through at least November 17.

So, what is the issue?

In an amicus curiae brief — friend of the court brief, filed by people or groups who aren’t parties to the litigation — filed at the Supreme Court in response to DOJ’s request, law professor Marty Lederman had raised the issue. (Jennifer Elsea, a legislative attorney, has raised similar points on Bluesky.)

Here’s how he summarized his point:

Here is the footnote from Solicitor General John Sauer’s application to the Supreme Court for DOJ that Lederman is referencing:

The plaintiffs did not even address the issue in their response at the Supreme Court.

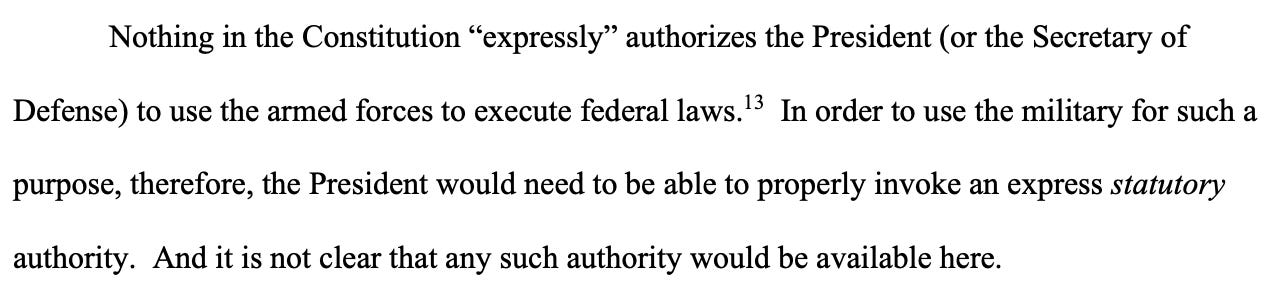

If Lederman is right, then the question quickly becomes whether Trump could deploy “regular forces” — meaning, the military — to cities. To that, Lederman noted that he is not suggesting Trump could do so.

“In offering this argument about the proper meaning of ‘the regular forces,’ amicus does not mean to suggest that the President has legal authority to direct regular military forces to execute federal laws in Illinois,“ Lederman wrote, highlighting the limits of the Posse Comitatus Act — which are also being litigated in challenges to Trump’s troop deployment efforts.

For his part, Lederman added:

Expect much more discussion of those possibilities in the coming weeks, given Wednesday’s Supreme Court order.

Also in Illinois

In addition to the Supreme Court order, there have been two other significant developments relating to Illinois on Wednesday.

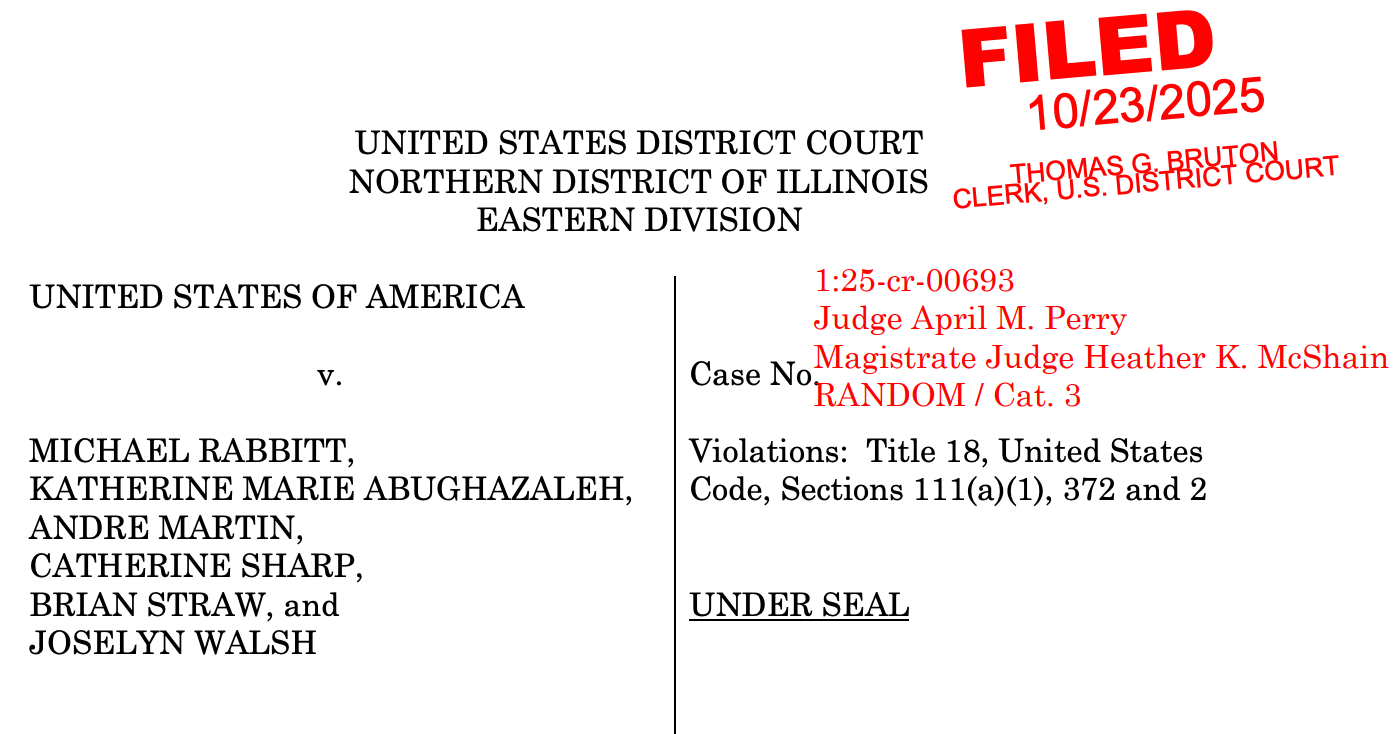

First, the Justice Department has secured the indictments of six protesters at the Broadview ICE facility, including congressional candidate Kat Abughazaleh.

Unsealed on Wednesday, the indictment — filed in the Northern District of Illinois — charges the six with “[a]ssaulting, resisting, or impeding certain officers or employees,“ as well as “[c]onspiracy to impede or injure officer.“

Abughazaleh released a video and statement on Bluesky, writing, “This political prosecution is an attack on all of our First Amendment rights. I’m not backing down, and we’re going to win.”

Tuesday’s motion by the U.S. Attorney’s Office to unseal the indictment was filed by U.S. Attorney Andrew Boutros and Assistant U.S. Attorney Sheri H. Mecklenburg. Boutros had previously worked in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago, but had been in private practice before re-joining the office in April to run it during the second Trump administration. Mecklenburg has worked for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago for most of the past 20 years.

The case was assigned to U.S. District Judge April Perry, who is overseeing the National Guard case. Initial appearance and arraignment is set for 3 p.m. PT November 5.

Order appealed

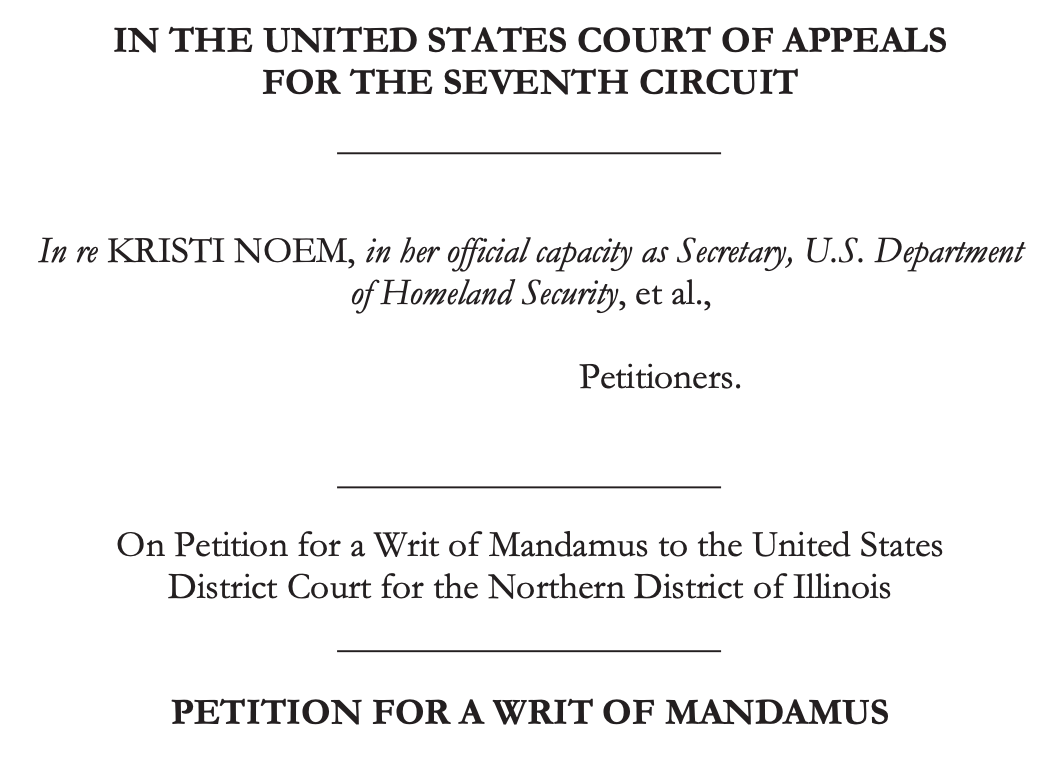

Later Wednesday, the Justice Department went to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in the case over treatment of protesters and journalists at the Broadview ICE facility and throughout the Chicago area, asking the appeals court to toss out a Tuesday order in the case.

In DOJ’s request — a petition for a writ of mandamus — the government asked the appeals court for an order that U.S. District Judge Sara Ellis vacate her Tuesday order, which required U.S. Border Patrol’s Gregory Bovino, who is playing a key role in operations in Chicago currently, to report to her daily.

Specifically, under the district court’s modified TRO in the case, “The Court orders Defendant Bovino to appear in court, in person, week days at 5:45 PM … to report on the use of force activities for each day.”

DOJ argued to the Seventh Circuit that the “extraordinary and extraordinarily burdensome order—entered without any formal finding that the government failed to comply with prior court orders—constitutes a clear abuse of discretion and violates the separation of powers.“

Tuesday’s order, despite DOJ’s careful yet inflammatory language, followed a hearing over plaintiffs’ arguments that government officials — including Bovino personally — had repeatedly violated the TRO Ellis had entered in the case limiting the use of force and putting other restrictions on the government in dealing with journalists and protesters.

Additionally at the Seventh Circuit, DOJ sought an “immediate administrative stay” because “the daily appearance requirement that the district court imposed less than 24 hours ago will begin today at 5:45pm.“

Two hours before Wednesday’s ordered appearance, however, the Seventh Circuit, in a brief order, granted that administrative stay, setting a very quick timeline for consideration of the mandamus petition by ordering plaintiffs to respond by 5 p.m. CT Thursday.

In this instance, I would not read much into the administrative stay. Regardless of whether the court ultimately agrees with DOJ, it is not surprising that it wants briefing and a moment to decide whether it is going to reject DOJ’s arguments.

![The President based his calling-forth order on his assessment that “the regular forces of the United States are not sufficient to ensure the laws of the United States are faithfully executed,” including in Chicago. Presidential Memorandum at 1, reprinted in D. Ct. Doc. 62-1, at 16. In so doing, he was relying upon 10 U.S.C. 12406(3), which provides in pertinent part that “[w]henever … the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States … the President may call into Federal service members and units of the National Guard of any State in such numbers as he considers necessary to … execute those laws.” The Solicitor General confirms (App. 30 n.4) that the “regular forces” to which the President referred in his Memorandum are personnel working within civilian federal law enforcement agencies—i.e., ICE and other entities within DHS, including the Federal Protective Service (FPS). It is highly uncommon, however, to refer to such civilian officials and employees as any kind of “forces” at all; and they certainly are not “the regular forces” to which § 12406(3) refers. “[T]he regular forces” to which the statute refers are, instead, the standing military forces of the Armed Services, within the Department of Defense. The President based his calling-forth order on his assessment that “the regular forces of the United States are not sufficient to ensure the laws of the United States are faithfully executed,” including in Chicago. Presidential Memorandum at 1, reprinted in D. Ct. Doc. 62-1, at 16. In so doing, he was relying upon 10 U.S.C. 12406(3), which provides in pertinent part that “[w]henever … the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States … the President may call into Federal service members and units of the National Guard of any State in such numbers as he considers necessary to … execute those laws.” The Solicitor General confirms (App. 30 n.4) that the “regular forces” to which the President referred in his Memorandum are personnel working within civilian federal law enforcement agencies—i.e., ICE and other entities within DHS, including the Federal Protective Service (FPS). It is highly uncommon, however, to refer to such civilian officials and employees as any kind of “forces” at all; and they certainly are not “the regular forces” to which § 12406(3) refers. “[T]he regular forces” to which the statute refers are, instead, the standing military forces of the Armed Services, within the Department of Defense.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8_7k!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F29a43727-117c-42db-8553-4ed09a8f1387_1326x1032.png)

![4 The district court also suggested that the statute’s reference to the “regular forces,” 10 U.S.C. 12406(3), means exclusively the “soldiers and officers regularly enlisted with the Army and Navy.” App., infra, 68a. Even the plaintiffs, however, accept that the “‘regular forces’” include “federal law and enforcement agencies of a nonmilitary nature.” C.A. App. A345 (emphasis added) (hearing transcript); see id. at A345-A347. That reading follows from the plain text, which refers to the “regular forces” who are engaged in “execut[ing] the law”—a description that naturally refers to federal law enforcement personnel. 10 U.S.C. 12406(3). Military forces, in contrast, do not regularly “execute the law.” See 18 U.S.C. 1385 4 The district court also suggested that the statute’s reference to the “regular forces,” 10 U.S.C. 12406(3), means exclusively the “soldiers and officers regularly enlisted with the Army and Navy.” App., infra, 68a. Even the plaintiffs, however, accept that the “‘regular forces’” include “federal law and enforcement agencies of a nonmilitary nature.” C.A. App. A345 (emphasis added) (hearing transcript); see id. at A345-A347. That reading follows from the plain text, which refers to the “regular forces” who are engaged in “execut[ing] the law”—a description that naturally refers to federal law enforcement personnel. 10 U.S.C. 12406(3). Military forces, in contrast, do not regularly “execute the law.” See 18 U.S.C. 1385](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jSRY!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5d5fb219-1504-451d-9518-949be147e34f_1302x372.png)

The judicial branch is shredding the rule of law under the guidance of the corrupt and unlawful SCOTUS

Uh, I think almost everyone has assumed that when the president is unable to execute the laws of the US, the order is National Guard first, Military Second. If not, then is the Insurrection Act the only way to get troops on the ground to "execute the laws?" That act seems to require a failure of the COURTS to enforce the laws. No matter what trump "proclaims" it seems we are far from that scenario,

Which is worse for the kinds of activities we are seeing in Portland and Chicago

---allowing Prez to federalize National Guard or

---interpret the Insurrection Act to allow the military without request of the governor when local courts and police forces are still active

(The case I could find regarding calling out troops without governor request or protecting an individual's rights (in the desegregation context) was with the MLK. Detroit, and Rodney King riots, which were WAY beyond the current protests)