SCOTUS will hear case over Biden admin and social-media content moderation

During the appeal, SCOTUS put lower courts' rulings on hold that would have barred the administration from some contact with social-media companies.

On Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court put on hold an injunction from two lower courts that would have limited the Biden administration’s ability to engage with social-media companies. At the same time, however, the court agreed to hear the underlying challenge to the administration’s actions — yet again bringing a fringe argument front and center on the national legal scene due to the extremism of the lower federal courts.

Murthy v. Missouri, as the case is now known at the Supreme Court, is a case brought by Missouri and Louisiana alongside private plaintiffs that include Gateway Pundit founder Jim Hoft. The challenge alleges that the Biden administration improperly coerced social-media companies to moderate content on their sites. Although a series of topics are addressed in the litigation, the case largely relates to COVID-19 and election-related content.

It is, in effect, a version of criticism that was advanced by the individuals granted access by Elon Musk to Twitter materials in dispatches known as the Twitter Files.

The legal argument advanced in the case goes that the administration’s efforts were so extensive that the private companies’ decisions should be considered state action. As such, the argument continues, the content moderation was a government action that violates the First Amendment.

Simply put, this is an argument alleging that the federal government had so much control over these private companies that courts should consider those companies’ actions to be government action limited by the First Amendment.

After two lower courts agreed, the case is now at the Supreme Court. With the injunction on hold for now — over the noted objection of three justices — arguments in the case will be heard in 2024 and a decision expected by late June.

The injunction

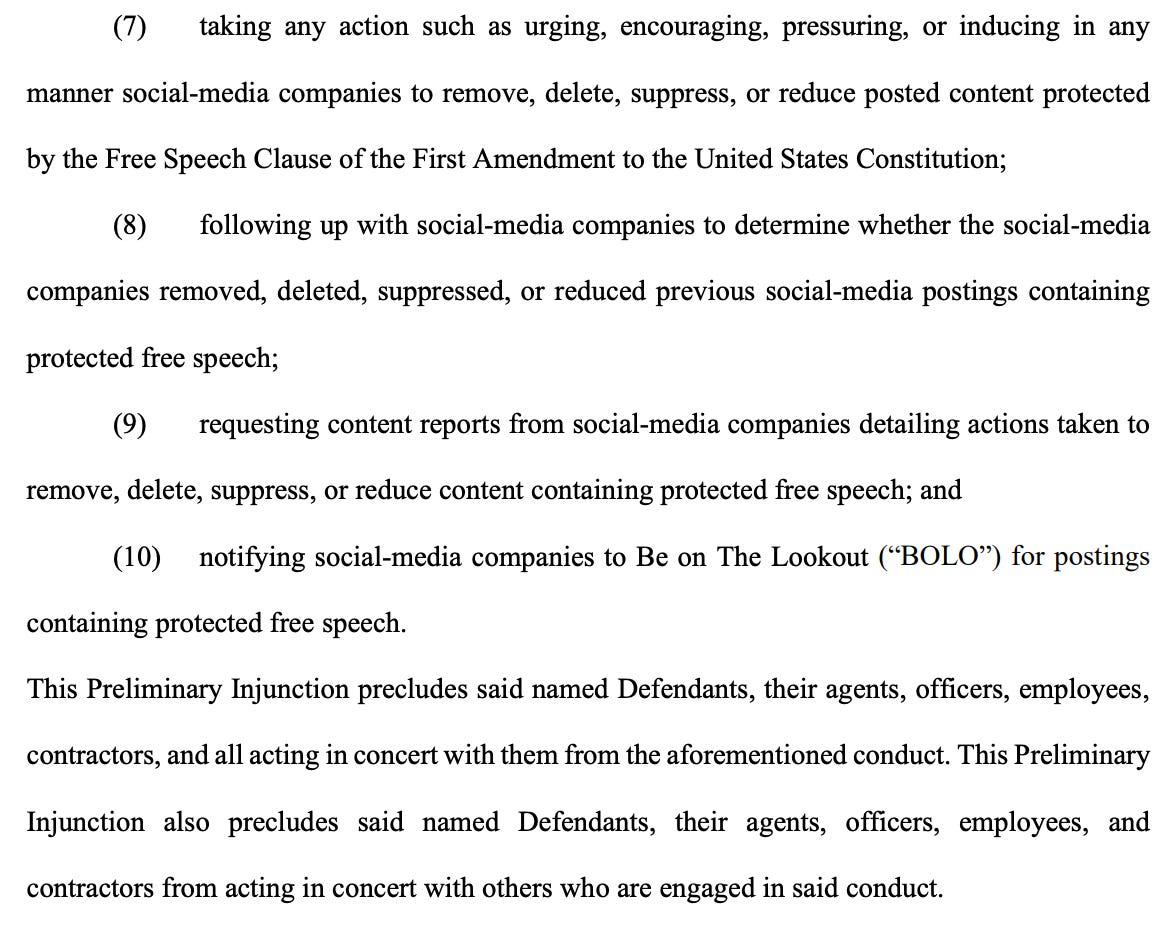

On July 4, U.S. District Judge Terry Doughty went along with the argument, issuing a 155-page Independence Day opinion in the case laying out all manner of ways in which he sided with the plaintiffs in their claims. The injunction he issued was disturbingly broad, purporting to bar a wide swath of the Biden administration from talking with social-media companies about several vaguely defined topics:

A violation of this injunction by any of the covered officials — from the White House press secretary to the surgeon general and beyond — would then risk the government being held in contempt whenever Doughty, a Trump appointee, decided they had violated the expansive order.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit — the most extreme right of the federal appeals courts — largely agreed with the underlying reasoning of Doughty’s opinion in a Sept. 8 ruling, holding that the plaintiffs had standing to bring their case and that the federal government had “likely coerced or significantly encouraged social-media platforms to moderate content” such that the moderation decisions became state actions likely violating the First Amendment.

The ruling from Judges Edith Clement, Jennifer Elrod, and Don Willett — two George W. Bush appointees and one Trump appointee, respectively — importantly did cut back most of the injunction itself. It also cut some of the entities and individuals (including the State Department) from being covered by the injunction. Although there was some very questionable procedural back-and-forth from the panel that resulted in the court adding one agency back into the injunction (the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency), the panel left the following narrowed injunction in place in its Oct. 3 decision in the case:

The Biden administration quickly went to the Supreme Court following the September ruling of the Fifth Circuit, asking the justices to put the injunction on hold and, if the court wished to do so, immediately grant the case for full review based on the initial stay request. It re-upped that request after the Oct. 3 decision.

On Friday, then, the justices did so, granting a stay of the injunction throughout the high court’s consideration of the case and agreeing to take up the case itself.

The moves mirror those seen in the medication abortion case challenging the government’s approval and treatment of mifepristone over the past 25 years. Although the justices haven’t yet decided whether they will hear that case, they stayed the lower court rulings earlier this year and a similar request from the Justice Department — asking the justices to overturn a Fifth Circuit ruling that narrowed a broad district court ruling — is pending.

Alito dissents

That was not all in the social-media case, though.

Justices Clarence Thomas, Sam Alito, and Neil Gorsuch would have let the injunction, as limited by the Fifth Circuit, to go into effect while the Supreme Court heard the case.

Alito, on behalf of the trio, wrote a four-page missive on how, in their view, the government did not meet its burden for getting the Supreme Court to issue a stay of the injunction:

The injunction applies only when the Government crosses the line and begins to coerce or control others’ exercise of their free-speech rights. Does the Government think that the First Amendment allows Executive Branch officials to engage in such conduct? Does it have plans for this to occur between now and the time when this case is decided?

Of course, this misses the primary argument being pressed by the Biden administration:

In extending the injunction [to CISA], the decision vividly illustrates the expansive and malleable nature of the Fifth Circuit’s novel test for state action, underscoring both the court’s errors on the merits and the grave harms imposed by an injunction requiring thousands of government employees to adhere to the Fifth Circuit’s standard on pain of contempt.

In other words, if the standard for finding state action is so vague that an appeals court can just change what agencies are covered by rewriting its opinion, how is the federal government supposed to know how it is being limited by the injunction?

In addition to the dismissive treatment of the government’s claims in its stay request, the statement from Alito — joined by Thomas and Gorsuch — does something else unusual. While such a dissent might be expected in a normal stay request matter, the dissent in this instance also signals a certain posture on the merits of the case itself —which the justices will now be hearing in the new year.

In concluding his dissent to the stay request, Alito wrote:

At this time in the history of our country, what the Court has done, I fear, will be seen by some as giving the Government a green light to use heavy-handed tactics to skew the presentation of views on the medium that increasingly dominates the dissemination of news. That is most unfortunate.

To the extent such a message was sent from the majority’s vote granting a stay, Alito voiced it into existence. The stay was a stay, unexplained. And while I have criticized the lack of reasoning in shadow docket orders, as have many others, Alito is the one who says — at least when he’s on the winning side of a vote — that such criticism is unfair.

In criticizing the court for granting a stay when, in his view, it was not justified, Alito generally seems to ignore the fact that the court granted merits review of the case. I would have thought Alito’s advice to Alito would be to wait for the merits case to address the merits. (Notably, that is, at least on the surface, what Alito did when he disagreed with the court’s stay in the mifepristone case.)

That is not what Alito did on Friday, instead lamenting the court’s action in a case that he characterized as “concern[ing] what two lower courts found to be a ‘coordinated campaign’ by high-level federal officials to suppress the expression of disfavored views on important public issues.”

If there’s any signal to take from Alito’s statement (and, to be clear, reading too much into any shadow docket ruling is a fraught task), I think it would be that he fears that Doughty and the Fifth Circuit will be reversed on the merits — and wants his partisan allies outside the court to know.

Nonetheless, the trio inside the court will almost certainly be attempting to win over a majority to their view in the coming months.

![SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES No. 23A243 (23–411) VIVEK H. MURTHY, SURGEON GENERAL, ET AL. v. MISSOURI, ET AL. ON APPLICATION FOR STAY [October 20, 2023] The application for stay presented to JUSTICE ALITO and by him referred to the Court is granted. The preliminary injunction issued on July 4, 2023, by the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, case No. 3:22–cv–01213, as modified by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on October 3, 2023, case No. 23–30445, is stayed. The application for stay is also treated as a petition for a writ of certiorari, and the petition is granted on the questions presented in the application. The stay shall terminate upon the sending down of the judgment of this Court. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES No. 23A243 (23–411) VIVEK H. MURTHY, SURGEON GENERAL, ET AL. v. MISSOURI, ET AL. ON APPLICATION FOR STAY [October 20, 2023] The application for stay presented to JUSTICE ALITO and by him referred to the Court is granted. The preliminary injunction issued on July 4, 2023, by the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, case No. 3:22–cv–01213, as modified by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on October 3, 2023, case No. 23–30445, is stayed. The application for stay is also treated as a petition for a writ of certiorari, and the petition is granted on the questions presented in the application. The stay shall terminate upon the sending down of the judgment of this Court.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0OxQ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8dd9e719-75c3-4386-b883-994be64a1380_866x742.png)

I see these internet content moderation cases as the second step in the process by conservative justices. Earlier this year in the Twitter v Taamneh case, the court ruled that the internet co.’s did have liability protection from 3rd party content. This was an important step in the actual goal which was to limit the scope of content moderation that these companies can perform.

With Twitter v Taamneh, the justices eliminated one of the potential justifications for content moderation. It’s hard for them to say that companies can’t moderate content if they are at risk of being sued.

I would expect we’ll see an ongoing push in this and future cases to limit the moderation of political and other forms of non-criminal / non-violent content.

This is the first article of yours that I've read. I appreciate the thorough summary. The legal terms you've used were approachable by a layman such as myself, as well I find that the points on which you've touched were mostly easy to follow. Readability 8/10