Religious supremacy, it is

Fake electors, too.

I’m overwhelmed by the response from people to the launch of my newsletter. I truly appreciate the more than 500 of you who signed up on day one, and thank you to all of the paid subscribers who are going to make this continued publication possible! It has been a really great start to what I hope will just keep growing over time.

If you want to know more about what I’m trying to do here, check out the About page!

If you’re reading this, please share it today and tell your friends to subscribe before we get more Supreme Court opinions and another day of the Jan. 6 Committee’s hearings on Thursday. I would so greatly appreciate it.

It was a busy first day of Summer, so let’s get to it.

SUPREME DECISIONS: The Supreme Court has been moving closer and closer to a view of the Constitution that places the guarantee of Free Exercise of religion not as an equal to the Establishment Clause but as superior to it — and other constitutional protections.

On Tuesday, the changes at the court — over the past few decades as well as the past few years — reached new ground. In an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, the court ruled that a Maine program that allows tuition assistance payments for certain students to go to public or private nonreligious schools violates the Free Exercise Clause because it does not allow those payments to go to religious schools.

The 6-3 decision in Carson v. Makin was not a surprise. But what happened is a big deal, particularly when you step back and look at where we’ve been and where we’re going.

Over the past 20 years, the Supreme Court went from a 5-4 decision that a state was permitted to allow individuals to choose to give state money to religious schools to Tuesday’s 6-3 decision that a state is required to do so if it’s allowing state money to go to nonreligious private schools.

The 2002 case, Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, was a landmark ruling that opened up the possibility of public funds going to support religious schools in a much more broad way than the court had previously allowed. At the time, the justices in the majority made a big point of two things: (1) the state chose this means of helping students in a failing school district and (2) it was, as then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote, “a program of true private choice” insofar as parents and not the state or school district chose how the money was to be used (although the dissenting justices questioned even that).

In his dissenting opinion, then-Justice John Paul Stevens warned the court — and the public — of what the decision could do:

Whenever we remove a brick from the wall that was designed to separate religion and government, we increase the risk of religious strife and weaken the foundation of our democracy.

More recently, the Supreme Court decided in 2017 that a state could not bar a church from participating in a state’s program to allow groups to get reimbursed for resurfacing playgrounds with recycled tires. Yeah, it’s the type of case that you think can’t possibly be that important. But, it was. The growing conservative majority used the case, Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, to undermine earlier Establishment Clause cases and the limits built into the 2002 case to get to today — all while Roberts claimed to be doing no such thing.

This was the focus of both Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor’s dissents on Tuesday. Notably, back in 2017, Trinity Lutheran was a decision where Sotomayor read from her dissent from the bench — a practice that justices generally keep to a minimum to signal when they are particularly disturbed by or in disagreement with a majority opinion. Disclaiming the court’s depiction of it as “a simple case” about recycled tires on a playground, Sotomayor was not having it:

This case is about nothing less than the relationship between religious institutions and the civil government—that is, between church and state. The Court today profoundly changes that relationship by holding, for the first time, that the Constitution requires the government to provide public funds directly to a church.

In Roberts’s opinion in that case, two of the justices — Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch — did not join one of his footnotes. What was the offending footnote?

This case involves express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing. We do not address religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.

[Emphasis added.] In other words, Roberts promised (joined by then-Justice Anthony Kennedy and Justices Samuel Alito and Elena Kagan) that the playground case didn’t have anything to do with using public money for, say, religious instruction at a religious school.

Until it did. On Tuesday, Roberts — again writing the opinion for the court — cited Trinity Lutheran and another case (involving a Montana tax credit for private school scholarship donors) to conclude that “[t]he ‘unremarkable’ principles applied” in those two cases “suffice to resolve this case.”

Showing the wisdom of Stevens’s 20-year-old warning, Sotomayor, in dissent on Tuesday, wrote that the circle was now squared:

Today, the Court leads us to a place where separation of church and state becomes a constitutional violation.

The Supreme Court issued four other decisions on Tuesday, which I discussed in my Twitter thread. The justices still have 13 cases outstanding, including the other religion case, Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, where the conservative justices are likely to take another brick out of that wall.

THE JAN. 6 COMMITTEE HEARINGS: On Tuesday, the Jan. 6 Committee heard damning testimony from two prominent Republican officials who faced Donald Trump’s ire for their refusal to overturn the election results in their states. Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers and Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger testified, as did Georgia election official Gabriel Sterling.

Their testimony was powerful, with Bowers talking about how the Trump team wanted him to violate his oath and referring to Trump and his post-election legal team as a “tragic parody.” Raffensperger testified that he couldn’t find the votes Trump wanted because, simply, “[t]here were no votes to find.”

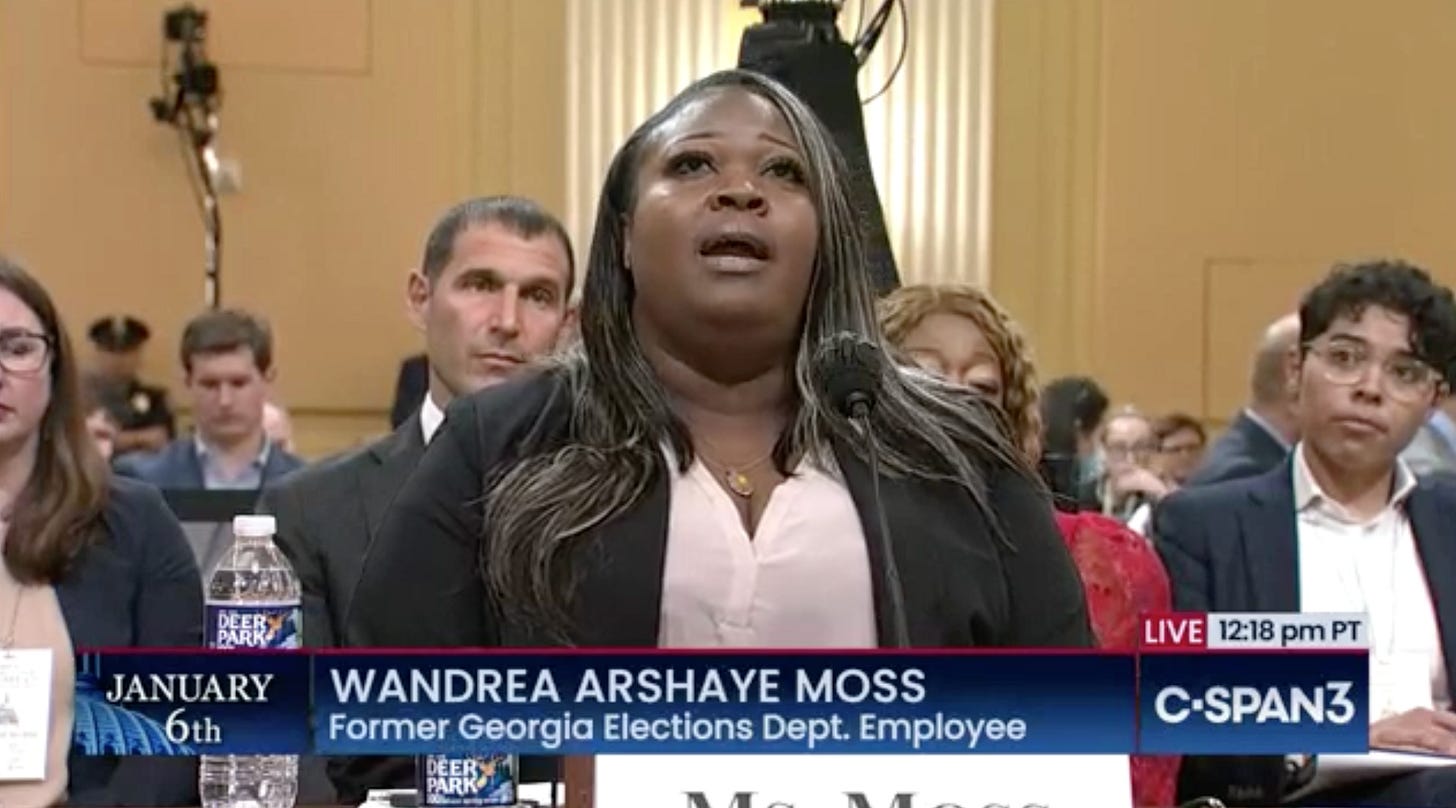

It was former election worker Wandrea Arshaye Moss’s testimony, though, that served as the emotional, and maybe moral, center of the day. Talking about serving as an election worker because her grandmother instilled in her the importance of voting, she testified about the threats she and her mother, Ruby Freeman, faced as a result of Rudy Giuliani’s unfounded and false attacks on them.

After hearing a clip of Trump attacking her mother by name on a call to Raffensperger, Moss was asked how the attacks made her feel: “I felt so bad. I felt bad for my mom, and I felt horrible for picking this job. ... I felt it was my fault for putting my family in this situation.” Read and watch this PBS News Hour story from Gabrielle Hays for more.

Here’s my Twitter thread from the Tuesday hearings.

Outside of the witness testimony, there were two main revelations that caught my eye.

First, Republican National Committee chair Ronna Romney McDaniel acknowledged in testimony to the Jan. 6 Committee that the RNC was “helping” the Trump campaign with gathering fake electors in states where Trump lost the election. I imagine that could become relevant at a later date.

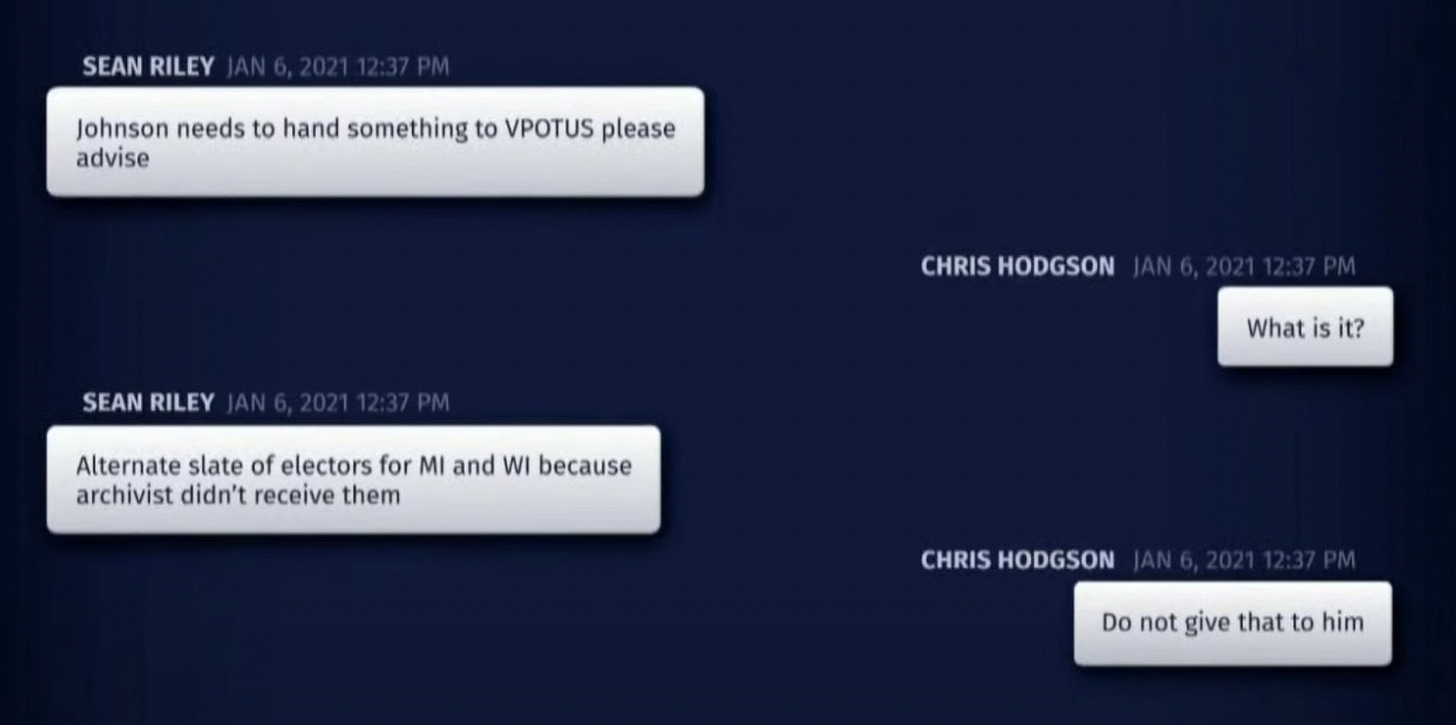

Second, what the hell is going on with Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.)? His chief of staff, Sean Riley, was texting with then-Vice President Mike Pence’s legislative director about fake slates of electors on Jan. 6, as Trump was giving his “Mike Pence” speech outside the White House and the Joint Session of Congress was about to begin.

Although Johnson told CNN’s Manu Raju he was “basically unaware” of what was going on — and that he didn’t know who’d given his office the two states’ fake slates of electors — there was definitely something interesting going on with Riley. According to Legistorm, Riley first began working for Johnson back in 2015. In February 2020, however, he left Johnson’s office — to work in the Trump White House Office of Legislative Affairs. He left the White House in Jan. 2021, and returned to Johnson’s office as chief of staff on Jan. 6, 2021.

So. That’s interesting.

A FINAL NOTE:

No.