Ohio gives local law enforcement the ability to charge up to $750 for public video footage

Gov. Mike DeWine defended the measure as a "workable compromise." Also, for paid subscribers: Closing my tabs.

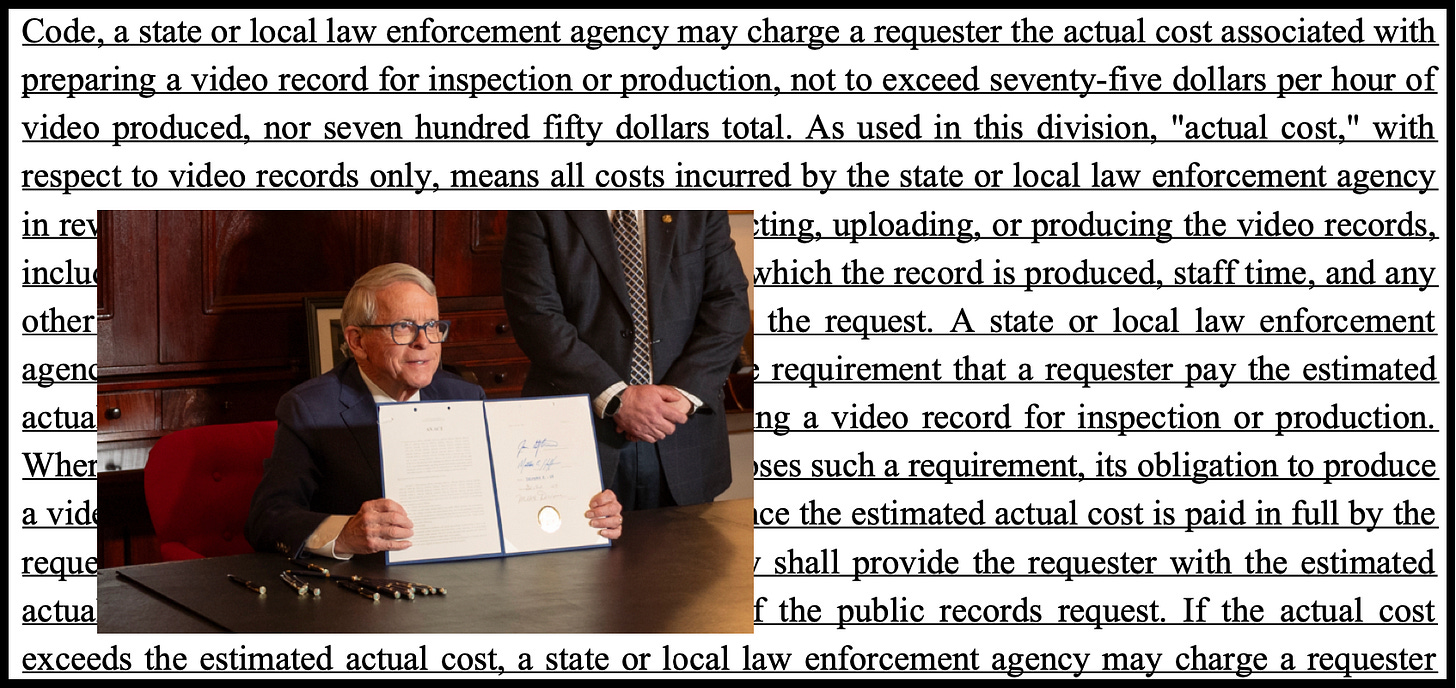

This past week, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine signed a bill into law that could enable law enforcement to charge up to $750 for a member of the public, including the media, to obtain bodycam footage of a deadly police encounter or video of a jail death.

Although the Republican governor used his line-item veto power to cut other provisions from the bill — and was urged to do so to cut this provision as well — he instead issued a separate statement explicitly expressing his support for this anti-transparency measure.

The provision asserts that “a state or local law enforcement agency may charge a requester the actual cost associated with preparing a video record for inspection or production, not to exceed seventy-five dollars per hour of video produced, nor seven hundred fifty dollars total.”

Here is the provision in H.B. 315, underlined, that is being added to the state’s public records law:

Although his statement accompanying the bill asserted that he “strongly support[s] the public’s — and the news media’s — right to access public records,” and claimed that the provision “doesn’t change that right,” DeWine also has been in government for most of the past 50 years and knows what the possibility of a $750 charge would do to many public records requests.

He then justified his support for the restriction on the public’s ability to access bodycam and and dashcam footage as a “changing technology” issue:

Law enforcement-worn body cameras and dashboard cameras have been a major improvement for both law enforcement investigations and for accountability. However, I am sensitive to the fact that this changing technology has affected law enforcement by often times creating unfunded burdens on these agencies, especially when it comes to the often time consuming and labor-intensive work it takes to provide them as public records.

"No law enforcement agency should ever have to choose between diverting resources for officers on the street to move them to administrative tasks like lengthy video redaction reviews for which agencies receive no compensation–and this is especially so for when the requestor of the video is a private company seeking to make money off of these videos. The language in House Bill 315 is a workable compromise to balance the modern realities of preparing these public records and the cost it takes to prepare them. Ohio law has long authorized optional user fees associated with the cost of duplicating public records, and the language in House Bill 315 applies that concept in a modern way to law enforcement-provided video records.

The problem with DeWine’s analysis is that any commercial ventures are the very ones least likely to have their access eliminated by a fee. Local media, on the other hand, let alone independent journalists or local activists, are the most likely to be effectively shut out by viewing such a cost as prohibitive.

If the effectiveness of the public records law is being stymied because of concerns of about “a private company seeking to make money off of these videos,” that — not the access of such videos to the public and for newsgathering operations — is what should be addressed.

Then, DeWine added three claims that are supposed to look like caveats to his support, but, in reality, they just serve as addition evidence of how bad this provision is.

"It is good that the language in House Bill 315 does not include a mandatory fee, but instead it is optional at the discretion of the agency.” This suggests that this is a soft bill, with exceptions, but what this actually means is that the worst agencies, least interested in public accountability, are able to take the harshest steps.

“It is also good the user fees are capped and directly related to the cost of production.” This just means it could have been worse. There didn’t need to be a cap, DeWine said, and it could have just been an outright fee.

"If the language in House Bill 315 related to public records turns out to have unforeseen consequences, I will work with the General Assembly to amend the language to address such legitimate concerns." This would be good to know, but, are the “consequences” really “unforeseen” to a man first elected to office in 1976?

More broadly, this argument turns good government on its head. DeWine is asserting that state government should enable local law enforcement to make it more difficult for the public it is supposed to be serving to observe its actions and hold it accountable as a first principle and then, if the public is somehow able to convince lawmakers that that this is causing harm, they will consider changes.

Closing my tabs

This Sunday, here are the tabs I’m closing: