Divergent responses to judge-shopping claims paint a disturbing picture

For the right, it's a "heads I win, tails you lose" life. Also: A recent filing in the Alabama investigation raises questions about a big claim in the panel's "inquiry" and report.

Over the past few years, there have been a torrent of stories and concern raised about how conservative lawyers go to jurisdictions where they are guaranteed conservative judges to bring cases seeking more and more extreme right rulings.

This sets up a process that I’ve detailed previously — allowing the 6-3 conservative U.S. Supreme Court to appear more reasonable than it is by rejecting a handful of the most extreme ideas, often coming out of the federal courts in Texas and going through the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, while nonetheless moving the law ever rightward by accepting some of the lower courts’ proposals.

Those stories paint an ever more disturbing picture when we step back and see the full canvas: As that debate was ongoing, federal judges in Alabama — other Republican appointees, operating mostly in secret — were subjecting dozens of civil rights lawyers to a two-year, and ongoing, “judge shopping” investigation into the motives behind their actions in three lawsuits challenging an anti-transgender law.

For those on the right — litigants, lawyers, or judges — it’s a "heads I win, tails you lose" life right now.

The Northern District of Texas, in particular, has had a system in place since September 14, 2022, in which litigants can guarantee that a case will be assigned to a certain judge if they file in a particular division of the district. In two divisions, file a case there and it will be heard by one of the most far-right judges in the nation: Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk in the Amarillo Division or Judge Reed O’Connor in the Wichita Falls Division. (Even before then, the cases had a 95% or 85% chance of being assigned to that judge, respectively.) Many far-right cases have been filed in these divisions — as well as the Fort Worth Division, where O’Connor gets 45% of the cases — as a result.

Contrast that with the story I laid out this week in Alabama, where lawyers were faced with the unexplained transfer, on Friday afternoon of a holiday weekend, of a case challenging the state’s ban on gender-affirming medical care for minors to the judge viewed as likely the worst draw in the Northern District of Alabama. Lawyers voluntarily dismissed that case and another case, as was their clients’ right under federal court rules. Those actions led the judge in question, U.S. District Judge Liles Burke, to ponder in a court order whether the lawyers actions constituted judge shopping. The next week, some of the lawyers, representing new clients, filed another case, as was their right. It ended up before Burke.

What happened next in these two districts shows the extent to which the "heads I win, tails you lose" mentality is reality.

In the Northern District of Texas, the judges rejected a policy of the Judicial Conference of the United States establishing that challenges to federal rules or regulations would be randomly assigned among all judges in the district, not just in the division where filed. It was as simple as that. A national policy was announced, garnering laudatory headlines. Within the month, the Northern District of Texas said no. Since then, the filing of new lawsuits in the Northern District of Texas challenging national policies has continued without district-wide random assignments. (This has all has gone so far that one Trump appointee, U.S. District Judge Mark Pittman has fought back, scrapping repeatedly with the Fifth Circuit.)

In the Northern District of Alabama — supported by judges in the Middle District and Southern District of Alabama — the chief judges launched an “inquiry” where attorney-client privilege was tossed aside and lawyers were put under oath to explain their motives for making their rules-permitted actions on their clients’ behalf as part of a three-judge panel’s investigation into the actions. The lawyers were, throughout the panel’s inquiry, subject to a gag order that prevented them talking with each other or anyone else about this, including the media, aside from the lawyers they had hired to represent them in the inquiry.

Eleven of the lawyers involved in Alabama trans cases are currently opposing a threat of sanctions from Burke — with a handful of those lawyers having been threatened further, with the possibility of jail.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and their allies continue filing cases in the Northern District of Texas unabated, meanwhile, and the Fifth Circuit keeps acting to help them keep their cases there.

That is the reality of our legal system in 2024.

What’s next in Alabama

In the wake of my reporting on the situation in Alabama — which you should take the time to read now if you haven’t done so already — the question is: What now?

There are, from my view, three overlapping matters that are at issue this month. Ultimately, the news tonight is in the third one, but, if you can, work with me to get there.

The show cause orders

This is the base issue. In spite of the arguments raised in their responses, will U.S. District Judge Liles Burke still issue sanctions against any or all of the 11 lawyers ordered to “show cause” why they should not be sanctioned?

As I detailed previously, all of the lawyers vigorously dispute the allegations, the panel’s presentation of the facts, and the applicable legal standards, as well as challenging whether they have received due process throughout all of this. The overarching question of why the rights of the parties under Rule 41 to voluntarily dismiss their case for any reason is not the beginning and end of this is yet to be answered. Subsequent questions about the other show cause order issues are wrapped up in the due process questions raised throughout, detailed extensively in a filing last month from three of the organizational lawyers, James Esseks, Carl Charles, and LaTisha Faulks.

As of now, the first show cause hearings are set for two of the private firm lawyers — Kathleen Hartnett and Michael Shortnacy — on June 24. The remaining nine hearings — for Esseks, Charles, and Faulks, as well as Jeffrey Doss, Melody Eagan, Jennifer Levi, Shannon Minter, Scott McCoy, and Asaf Orr — are currently set for June 27 and 28.

The Q&A document show cause order

This was the issue that prompted my initial reporting on this matter. Will Burke try to force the lawyers to turn over the document, which they assert is protected by attorney-client privilege, by finding that the crime-fraud exception allows him or a special master to review the document?

If he orders that, virtually everyone (including Burke) seems to understand that one or more of the lawyers subject to this show cause order — Hartnett, Esseks, Charles, and Faulks, along with Milo Inglehart, a lawyer who was released from the investigation in 2022 — will go to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, seeking a writ of mandamus blocking Burke’s order.

The document at issue was prepared in response to the initial May 10, 2022, order from the panel that the lawyers report to Alabama for a May 20, 2022, hearing about Burke’s judge-shopping questions. Given the short timeframe and the need to have counsel for the hearing, a document was created — apparently in a shared Google document or similar service — to help prepare the retained lawyer, Barry Ragsdale, about what had happened and what the lawyers thought could come up at the May 20 hearing.

Of course, at the time, none of the lawyers realized that this was going to be the beginning of a multi-year process. And yet, the implication of the show cause order from Burke this year is that he needs to see the document to determine whether it was part of an effort to deceive the court.

Although Burke suggested an opinion would be forthcoming at the conclusion of a hearing on the issue held on May 28, there has not been any public order and there have been no public filings on the issue at the Eleventh Circuit as of Sunday. This is an important issue on its own, but it is also notable because of the quickly approaching show cause hearings — for which Burke apparently believes this document could be relevant. Hartnett is one of the lawyers named in the Q&A document show cause order, yet her underlying show cause hearing is set for just 15 days from now.

The judicial notice filing

On May 31, as I was preparing my report on the Alabama judge-shopping inquiry, the two Alabama lawyers who provided the one legal team with much of their in-state expertise when these cases were being filed in 2022, Jeffrey Doss and Melody Eagan, filed with Burke a motion to have the court take judicial notice. Under federal rules, courts can take “judicial notice” of any “fact that is not subject to reasonable dispute.” They must do so if presented with the information by a party — as happened here.

So, the question here is: What are Doss and Eagan seeking to have Burke take judicial notice of, and why does it matter?

What is this?

It’s the trial that the panel told the lawyers at the May 20, 2022, hearing was the reason why U.S. District Judge Annemarie Axon transferred the first-filed case challenging the ban, Ladinsky, to Burke, who that day had been assigned the second-filed case, Walker, after it was transferred to the Northern District from the Central District by U.S. District Judge Emily Marks. (All three of these judges — Axon, Burke, and Marks — are Trump appointees.)

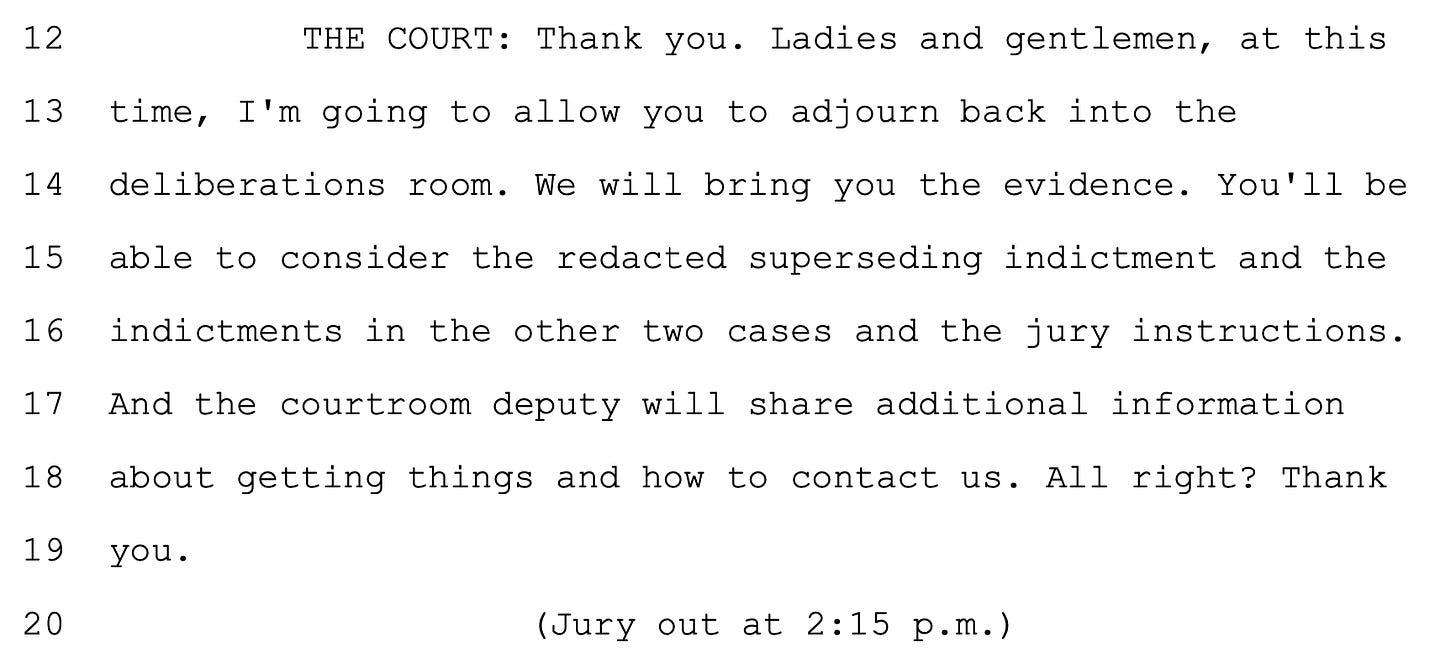

Here’s how the panel — U.S. District Judges Keith Watkins and David Proctor, George W. Bush appointees, and U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Beaverstock, a Trump appointee — introduced the transfer in its “Final Report of Inquiry” in October 2023:

Later, the report detailed the way the panel initially presented the transfer to the lawyers at the May 2022 hearing:

The Panel explained at the May 20 hearing that Judge Axon transferred Ladinsky because she was then “on day four of what was scheduled to be a two-plus-week criminal trial, an 18-defendant case with four defendants at trial, and quite a lot of moving parts in that criminal case. And based upon judicial efficiency and economy, Judge Burke took the case. Judge Axon would not have had the judicial resources to start the case right away …. [T]here was a simple determination that we would have the judge who could handle the case and wasn’t in a long criminal trial to handle that case.”

In its final report, the panel went on to chastise the lawyers that “even if counsel had questions about that process, those questions do not even come close to justifying counsel’s wholly unwarranted suspicions regarding why the case was assigned to Judge Burke.”

Finally, the panel asserted that the misconduct of the lawyers included “claiming that the dismissal was because Judge Axon did not explain the reassignment of Ladinsky and Judge Burke set Walker for a status conference in Huntsville on April 18.”

In sum, according to the panel, Axon transferred Ladinsky to Burke at 4:41 p.m. Friday, April 15, 2022, because Axon was “on day four of what was scheduled to be a two-plus-week criminal trial.” And questioning that reassignment was offensive enough to be misconduct.

The docket numbers cited in Doss and Eagan’s filing, however, show that the Williamson jury was already in deliberations before Axon transferred Ladinsky to Burke. What’s more, the verdict was reached by 3:50 p.m. the next deliberation day, Monday, April 18.

Docket No. 601 cited in Doss and Eagan’s judicial notice filing is the verdict. The other three docket numbers are the transcripts of the Williamson trial from April 14, 15, and 18, 2022. Notably, on April 15, Axon oversaw the closing statements and sent the jury into deliberations room at 2:15 p.m.

And, on Monday, April 18, the jury was brought back into the courtroom after reaching its verdict at 3:50 p.m.

To my knowledge, neither of these aspects of the Williamson case have previously been publicly reported.

Why does this matter?

The judicial notice filing reiterated that Rule 41 should make all of this irrelevant. But, it goes on, “[T]he Panel provided an explanation during the hearing and in the Final Report of Inquiry about why the case was transferred to this Court,” adding that the panel then “referenced that explanation as grounds for misconduct findings in the Final Report of Inquiry.” Then, judicial notice filing stated, “If this Court is inclined to examine the Respondents’ motivations for dismissing Ladinsky, the court records cited above regarding Williamson should be considered as well.”

In short, the filing essentially says, “If you’re going to consider this claim — which, again, you shouldn’t because of Rule 41 — let’s actually look at this claim.“

This information raises questions about the panel’s story that Axon was concerned about a two-week trial when she transferred Ladinsky to Burke — because the trial was already to the jury. To be sure, Axon didn’t know that the jury would reach a verdict the next day, but the lawyers for Doss and Eagan want to make sure that it is in the record — before Burke moves forward with this — that Axon transferred the case to Burke more than two hours after the trial that allegedly was the reason she needed to transfer the case had gone to the jury.

Additionally, and to be clear, this is about the panel. From all that I can gather, Axon has never said any of what the panel claimed publicly. As such, all of this reasoning is primarily attributable to the panel at this point. If read with knowledge about the status of Williamson at the time of the Ladisnky transfer, moreover, the panel’s language is extremely carefully worded. It is, at the least, notably incomplete.

This information adds another layer of questions about the panel’s behavior in this inquiry — which it repeatedly insisted was “not adversarial” — and in its report, which, in turn, raises additional questions about how much Burke can and should rely upon that report as he considers what to do now.

Ultimately, as I reviewed all of this, it served as a reminder of how closed off this whole investigation has been from public scrutiny — and as a warning to all about why that’s such a big problem.

![On April 15, 2022, Judge Axon was presiding over day four of a criminal trial with multiple defendants, which at the time of trial was anticipated to last for more than two weeks.1 So, at 4:41 p.m., considering the pending motion for a preliminary injunction in Walker and the pressing claims for injunctive relief in the Ladinsky complaint, Judge Axon transferred Ladinsky to Judge Burke “[i]n the interest of efficiency and judicial economy.” (Ladinsky, 5:22-cv-447-LCB (N.D. Ala.), Doc. # 14). On April 15, 2022, Judge Axon was presiding over day four of a criminal trial with multiple defendants, which at the time of trial was anticipated to last for more than two weeks.1 So, at 4:41 p.m., considering the pending motion for a preliminary injunction in Walker and the pressing claims for injunctive relief in the Ladinsky complaint, Judge Axon transferred Ladinsky to Judge Burke “[i]n the interest of efficiency and judicial economy.” (Ladinsky, 5:22-cv-447-LCB (N.D. Ala.), Doc. # 14).](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pSKv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F160847c8-9ff0-48bd-92d4-a38fd5790272_1746x592.png)

It's Kafkaesque however you analyze it.

I've been operating under the assumption that if Republicans win the election, what's left of democracy, the rule of law, and certainly human and civil rights, are gone. In which case logical arguments won't make a difference to anything anymore.

So the case to consider is if Biden wins the election. Setting aside the violence that is certain to follow from Republican sympathizers, if we manage to move forward continuing under the current constitutional system, where are we headed?

Considering the sheer defiance coming from the federal judiciary, will that branch finish off what the Republicans couldn't in the election? Is judicial reform an imperative for the republic to survive? Meaning Democrats would have to win both houses of Congress in November too, such that legislation could be passed? (The Senate will be almost impossible to keep this year). Would SCOTUS accept any oversight of the judiciary at all, or will we have a constitutional crisis between the judiciary and the other two branches?

TL;DR - Exactly how many hoops do we have to jump through for anything to ever be okay in this country again? I'm trying to figure out, as a practical matter, where to look for light at the end of the tunnel. What do we need to do?

Damn this is good, Chris

And...the panel...lied. How can we read this any other way?. And why do I feel this is just going to make Burke even angrier and more vindictive?