District judge presses forward with mass-firings challenge following SCOTUS's order

Judge Susan Illston provided a great example on Friday of how to deal with the current Supreme Court in an order that the Trump admin turn over its mass-firing plans.

How do you deal with a reactionary, far-right U.S. Supreme Court majority in this moment of the Trump administration’s repeated lawlessness if you are a federal district judge who believes in the rule of law?

You take the Supreme Court’s rulings at face value — no more and no less than what the justices themselves are actually willing to say — and move forward, carefully.

Federal district judges, by and large, have shown they are up to the task of this moment — regardless of the president who appointed them. (It’s as we go up the line — to appeals courts and then the Supreme Court — that the rulings start to look more and more politicized.)

The latest great example of smart, careful district court judging came from U.S. District Judge Susan Illston on Friday, when she ordered the Trump administration to turn over agency mass-firing plans by noon Wednesday.

After the U.S. Supreme Court issued its two-paragraph order tossing out Illston’s preliminary injunction that had stopped the Trump administration from implementing government-wide mass firings, the plaintiffs asked for Illston to consider anew requests that the government turn over the specific agency proposals for those reductions-in-force (RIFs), which DOJ opposed. Those plans — Agency RIF and Reorganization Plans (ARRPs) — were not a part of the initial injunction before the Supreme Court. That injunction only addressed the challenge to President Donald Trump’s executive order and the joint implementation memo from the Office of Personnel Management and Office of Management and Budget.

“We express no view on the legality of any Agency RIF and Reorganization Plan produced or approved pursuant to the Executive Order and Memorandum,” the unsigned order from the Supreme Court stated — a point reiterated by Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her brief concurrence.

All of which brought us to Friday.

What did Illston, a Clinton appointee who has been on the bench since 1995, show us?

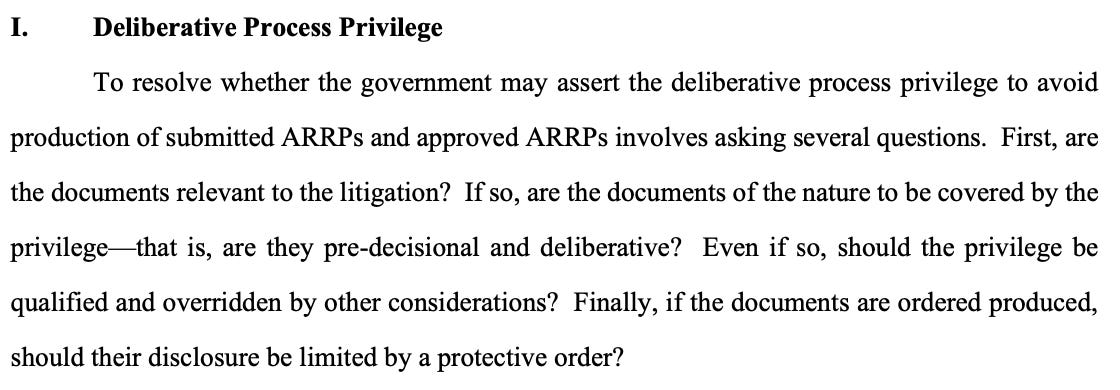

The question before Illston was a discrete, but important, one: Can the Trump administration invoke “the deliberative process privilege to avoid production of submitted ARRPs and approved ARRPs“?

Ultimately, Illston “assume[d] without deciding that at least some ARRPs may include pre-decisional and deliberative materials,“ because she found that “the need for accurate fact-finding overrides the government’s interests in non-disclosure.“ (More on the protective order question below.)

How Illston did this, though, is key.

District court judges — like justices — have lifetime tenure. If there were ever a time to rely on that reality, it’s now.

Illston implemented — and gave DOJ — no more than the Supreme Court’s ruling. In so doing, she provided a perfect example of a judge plainly explaining a Supreme Court order, giving the order no more weight or effect than the Supreme Court itself was willing to provide — noting that the majority provided little reasoning for their order, adding that it was “inherently preliminary,” and quoting the portion I noted above that had left this specific issue unresolved.

In addition to plainly and clearly describing Supreme Court orders, district court judges need not treat the Justice Department as a good-faith litigant when it has proven repeatedly that it is not. This is a tough move for some judges — particularly those who had long careers at DOJ before becoming judges — but it has become necessary. Under Attorney General Pam Bondi’s leadership, the independence of the department from the White House has been eviscerated — intentionally and publicly.

As Illston showed, when DOJ makes nonsensical arguments, judges need not “countenance” them.

As Illston concluded, “Defendants may not attack plaintiffs’ case for failing to ‘challenge the content of particular ARRPs’ while simultaneously withholding those same ARRPs.“

In a later part of her ruling, Illston illustrated this role of a district court judge in addressing today’s Justice Department even more plainly:

“The government’s shifting positions degrade the Executive’s credibility ….”

Indeed.

What’s more, judges also need not hide their eyes from the broader landscape. Although DOJ argued that release of the AARPs could harm government recruitment, plaintiffs and Illston called that out.

“The damage to the federal government’s employee recruitment, retention, and labor relations has already been done, and the wounds are self-inflicted,” Illston explained.

Next, the strongest judges in this moment are careful. Illston prevented an easy reversal by limiting the release of the AARPs — issuing a protective order that will only allow the AARPs to be seen, for now, by the court and counsel.

Finally, Illston did what is becoming the hallmark of smart judging today: issuing unambiguous orders with clear deadlines.

Three specific tasks, clearly explained, and they all need to be done by Noon Pacific Time Wednesday.

![A. Relevance Defendants’ recent filing argues repeatedly that the Supreme Court’s order staying the preliminary injunction “effectively ends this case[.]” See Dkt. No. 208 at 1. This Court disagrees with defendants’ reading. In granting the preliminary injunction, this Court did not reach several of the claims in the amended complaint. The Supreme Court’s stay of the injunction therefore did not have any bearing on those claims. Moreover, the high Court’s terse order to stay an injunction—and its statement that “the Government is likely to succeed on its argument that the Executive Order and Memorandum are lawful”—are inherently preliminary.3 See Trump, 2025 WL 1873449, at *1. The Court of Appeals still must determine whether the preliminary injunction is appropriate, a question defendants raised to that court and a question that may ultimately return to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, here below, these preliminary decisions do not foreclose claims or otherwise halt proceedings on the merits on any claim in this case. Further, in granting the stay, the Supreme Court stated, We express no view on the legality of any Agency RIF and Reorganization Plan produced or approved pursuant to the Executive Order and Memorandum. The District Court enjoined further 3 Since the Supreme Court included no explanation of its conclusion, this Court cannot say whether the Supreme Court determined the claims underlying the preliminary injunction fail as a matter of law or if the evidentiary record has not yet sufficiently developed to support the claims. A. Relevance Defendants’ recent filing argues repeatedly that the Supreme Court’s order staying the preliminary injunction “effectively ends this case[.]” See Dkt. No. 208 at 1. This Court disagrees with defendants’ reading. In granting the preliminary injunction, this Court did not reach several of the claims in the amended complaint. The Supreme Court’s stay of the injunction therefore did not have any bearing on those claims. Moreover, the high Court’s terse order to stay an injunction—and its statement that “the Government is likely to succeed on its argument that the Executive Order and Memorandum are lawful”—are inherently preliminary.3 See Trump, 2025 WL 1873449, at *1. The Court of Appeals still must determine whether the preliminary injunction is appropriate, a question defendants raised to that court and a question that may ultimately return to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, here below, these preliminary decisions do not foreclose claims or otherwise halt proceedings on the merits on any claim in this case. Further, in granting the stay, the Supreme Court stated, We express no view on the legality of any Agency RIF and Reorganization Plan produced or approved pursuant to the Executive Order and Memorandum. The District Court enjoined further 3 Since the Supreme Court included no explanation of its conclusion, this Court cannot say whether the Supreme Court determined the claims underlying the preliminary injunction fail as a matter of law or if the evidentiary record has not yet sufficiently developed to support the claims.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!PtRj!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F78cee981-3647-4638-8a10-ea4afac84942_1332x1228.png)

![II. The "40 RIFs in 17 Agencies" In defendants' application for a stay to the Supreme Court, the U.S. Solicitor General represented that "about 40 RIFs in 17 agencies were in progress and are currently enjoined." Application for Stay at 32-33, Trump v. Am. Fed. of Gov't Emps., AFL-CIO, No. 24A1174 (U.S. June 2, 2025). Defendants made this assertion to the Supreme Court to highlight the urgency of 9 Case 3:25-cv-03698-SI Document 214 • Filed 07/18/25 Page 10 of 11 their stay request and the extent of irreparable injury facing the government. Yet defendants now back-track, telling this Court that, actually, "those RIFs have not been finalized, many were in an early stage, and some are not now going forward." Dkt. No. 208 at 12. Defendants have submitted a declaration from Noah Peters, a senior advisor in OPM, stating that the numbers given to the Supreme Court "reflect[] results from an early, initial step in RIF planning" and "did not derive from how many RIFs were mentioned in any Agency RIF and Reorganization Plans (ARRPs)." Dkt. No. 208-1 14 11-12. But if RIFs do not flow from ARRPs, Executive Order 14210, or the OMB/OPM Memo at issue in this case, they would not have been enjoined by the Court's preliminary injunction. The government's shifting positions degrade the Executive's credibility and further underscore the need for an examination of the documents themselves. The Court repeats a query that it previously posed: if the ARRPs are non-final planning documents that do not commit an agency to take any specific action, pursuant to what, then, are the agencies implementing their large-scale reorganizations and RIFs? II. The "40 RIFs in 17 Agencies" In defendants' application for a stay to the Supreme Court, the U.S. Solicitor General represented that "about 40 RIFs in 17 agencies were in progress and are currently enjoined." Application for Stay at 32-33, Trump v. Am. Fed. of Gov't Emps., AFL-CIO, No. 24A1174 (U.S. June 2, 2025). Defendants made this assertion to the Supreme Court to highlight the urgency of 9 Case 3:25-cv-03698-SI Document 214 • Filed 07/18/25 Page 10 of 11 their stay request and the extent of irreparable injury facing the government. Yet defendants now back-track, telling this Court that, actually, "those RIFs have not been finalized, many were in an early stage, and some are not now going forward." Dkt. No. 208 at 12. Defendants have submitted a declaration from Noah Peters, a senior advisor in OPM, stating that the numbers given to the Supreme Court "reflect[] results from an early, initial step in RIF planning" and "did not derive from how many RIFs were mentioned in any Agency RIF and Reorganization Plans (ARRPs)." Dkt. No. 208-1 14 11-12. But if RIFs do not flow from ARRPs, Executive Order 14210, or the OMB/OPM Memo at issue in this case, they would not have been enjoined by the Court's preliminary injunction. The government's shifting positions degrade the Executive's credibility and further underscore the need for an examination of the documents themselves. The Court repeats a query that it previously posed: if the ARRPs are non-final planning documents that do not commit an agency to take any specific action, pursuant to what, then, are the agencies implementing their large-scale reorganizations and RIFs?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!dKEp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F75ab2b9c-058b-4fb4-86cf-bd54bf88e837_1124x1284.png)

As a former federal clerk and long federal criminal defense practice, I have seldom read a district court's order that filled me with such joy.

Very well done Judge Illston!