Florida high court upholds abortion ban — and puts abortion on the ballot

A third decision on Monday also approves a marijuana legalization ballot measure for the fall.

The Florida Supreme Court on Monday allowed the state’s six-week abortion ban to go into effect in an opinion that “recede[s]” from prior decisions applying the state’s constitutional “Privacy Clause” to protect abortions. In another opinion issued at the same time, however, the court also approved a proposed constitutional amendment ballot measure to protect abortion rights being placed on the November ballot.

In a third opinion also released Monday, the Florida Supreme Court approved a proposed constitutional amendment to legalize marijuana for adults to be placed on the November ballot.

The 6-1 ruling overturning Florida precedent on abortion has a very real effect on people seeking abortion care in the state. That fact — and the court’s decision reversing its own understanding of state law based in part on the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade — should not be ignored here.

At the same time, though, the trio of rulings changed the politics of the coming months in an instant when the court announced the rulings at 4:02 p.m. Monday. Given the strong support voters — even those in strong Republican states — have shown for abortion rights and marijuana legalization, the ballot placement decisions both could lead to substantive changes for Floridians and to changes for the politics of the state this fall.

The abortion measure only was approved for ballot placement on a 4-3 vote, with all three female justices on the court — all DeSantis appointees — voting against letting the people be able to vote on the question. The marijuana measure was approved for ballot placement on a 5-2 vote, with two of those three same justices dissenting. Under Florida law, the constitutional amendments will require 60% voter support to be approved.

As to new abortion restrictions in Florida for now, however, the court concluded that “there is no basis under the Privacy Clause to invalidate the statute.” To do so, Justice Jamie Groshhans, a DeSantis appointee, had to overturn decades of precedent. She was joined in her opinion for the court by five of the court’s other justices.

Although the ruling technically addressed Planned Parenthood of Southwest and Central Florida’s challenge to the state’s 15-week abortion ban, the ruling also puts in motion the clock for the six-week ban passed by the legislature in 2023 to go into effect.

As Justice Jorge Labarga, a Crist appointee, addressed in his dissenting opinion, “[T]he Act’s six-week ban will take effect in thirty days” following Monday’s decision under the explicit term’s of the six-week ban statute.

First, overturning precedent

In order to reach Monday’s decision, the majority had to overturn the court’s own 1989 precedent — and subsequent cases — interpreting the state’s own 1980 Privacy Amendment, which guarantees “the right to be let alone and free from governmental intrusion into . . . private life.”

As Labarga wrote, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization “did not force the state of Florida into uncharted territory” because Florida already had a post-Roe constitutional privacy provision that had been interpreted in light of that reality.

And yet, for Groshhans and today’s Florida Supreme Court majority — of which five of the seven justices were appointed by Gov. Ron DeSantis — Dobbs changed everything.

Because the 1989 Florida Supreme Court decision — referred to as T.W. — “adopted Roe’s notions of privacy and its trimester framework as matters of Florida constitutional law,” Grosshans wrote, the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court later “repudiated” Roe justified Monday’s decision reexamining the 1980 Florida amendment and concluding the 1989 Florida Supreme Court was wrong.

In light of T.W.’s analytical deficiencies and subsequent U.S. Supreme Court decisions rejecting the Roe framework on which T.W.’s reasoning depended, our assessment of the challenged statute requires us to examine the Privacy Clause and, for the first time in the abortion context, consider the original public meaning of the text as it was understood by Florida voters in 1980.

The court did so by looking to dictionary definitions and other context clues, including lawmakers’ discussions, ultimately concluding there was not evidence abortion was intended to be covered by the amendment. Instead, Grosshans wrote, the 1989 court “read additional rights into the constitution based on Roe’s dubious and immediately contested reasoning, rather than evaluate what the text of the provision actually said or what the people of Florida understood those words to mean.”

For his part, the dissenting Labarga was not buying it, writing, “Florida media coverage after Roe illustrates that in 1980 Florida voters would have understood the privacy amendment to encompass the right to an abortion. The wealth of primary sources from Florida strongly indicates what voters would have known.”

And yet, in 2024, Grosshans and today’s Florida Supreme Court decided that they had a better handle on the 1980 election than the 1989 court had, concluding: “The decision to extend the protections of the Privacy Clause beyond what the text could reasonably bear was not ours to make.” The T.W. decision, today’s court held, was “clearly erroneous.”

From there, the Florida court again relied on Dobbs — to reject Floridians’ reliance on T.W. and the understanding of the state’s privacy protections since then. “[T]he Supreme Court’s reasoning in Dobbs shows why reliance does not justify keeping T.W.,” Grosshans wrote. The court then formally rejected T.W. and subsequent abortion decisions, “reced[ing]” from them.

With that, 35 years of Florida law was washed away.

A final note on this ruling: Although Grosshans wrote that this is an abortion-only decision, unlike Dobbs, she affirmatively leaves the door open to future challenges, writing only that “we do not take up the State’s invitation now to” dramatically scale back the scope of the privacy Clause to protect only “informational privacy,” and not “decisional or autonomy rights.”

Not exactly reassuring — even compared to Justice Sam Alito’s comments in Dobbs about the limits of that ruling.

But now, a November abortion vote

At the same time on Monday, four justices of the Florida high court gave the go-ahead to voters’ effort to do what the court on Monday said voters had not done in 1980.

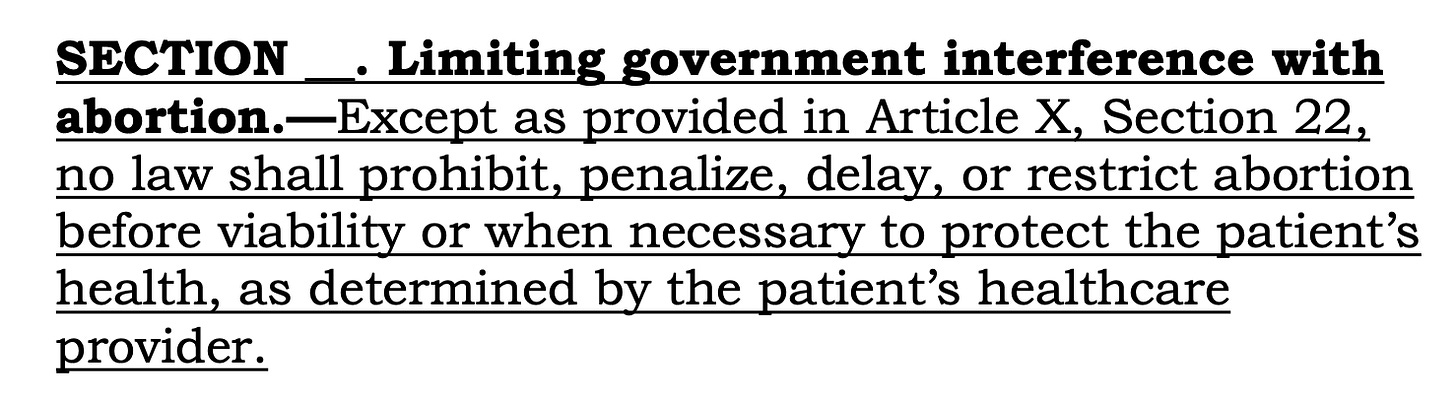

In a per curiam opinion — an unsigned opinion for the court — the court approved a proposed constitutional amendment relating to abortion rights to be on November’s ballot, rejecting claims that the provision violates the state’s single-subject requirement and that the ballot title and summary language are misleading.

The reason for the opinion being per curiam became clear as one reads the opinion. The majority is very unhappy with the dissenting justices — DeSantis’s three most recent appointees to the court, including Grosshans. The others are Justices Renatha Francis and Meredith Sasso.

The majority included Labarga and Justice Charles Canady, both Crist appointees, and Chief Justice Carlos Muñiz and Justice John Couriel, both DeSantis appointees.

After highlighting some of the three dissenting justices’ complaints that, in their view, the ballot text and summary are vague, the per curiam decision — which, admittedly, reads awkwardly given its unsigned status — stated:

Lawyers are adept at finding ambiguity. Show me the text and I’ll show you the ambiguity. The predominant reasoning in the dissents would set this Court up as the master of the constitution with unfettered discretion to find a proposed amendment ambiguous and then to deprive the people of the right to be the judges of the merits of the proposal. … We decline to encroach on the prerogative to amend their constitution that the people have reserved to themselves.

Ouch.

A final note on this decision: The per curiam decision highlighted, again in a footnote, that Monday’s decision in the privacy case leaves “unsettled” the “nature” of the “complex” questions surrounding fetal “personhood” protections in Florida — which Grosshans discussed in her dissent because of her view that the ballot measure “could, and likely would, impact” the understanding of “personhood” in Florida and thus should be discussed in the summary.

In sum, November’s vote is important.

And now, after Monday, both abortion rights and marijuana legalization will be on Florida’s ballot.

Fetal 'personhood' is a daft idea, but, even if a fetus were a person, that shouldn't have to raise such difficult questions. Why would a fetus have rights to someone else's body? What other persons in our law have rights to another's body?

It would have to be interpreted instead as a form of parental responsibility. And that raises the question of what constitutes consent to parenthood. The simple act of becoming pregnant - which can easily result from both nonconsensual sex and from the failure of a contraceptive, even when used responsibly - cannot possibly be sufficient to yield legal consent to parenthood.

Properly understood, the instances in which even a fetus which were a legal person would have rights that would conflict with the rights of the person whose body it inhabits, should be rare indeed.

In the coming 30 days every woman in Florida should stock up on Plan B.