Civil asset forfeiture is on notice — but came out unscathed at SCOTUS for now

Five justices on Thursday encouraged more civil forfeiture challenges, even as six justices rejected the retention hearings sought in an Alabama case.

Thursday’s U.S. Supreme Court decision in a civil asset forfeiture case appeared to be an interim decision of sorts. It was a loss for challengers in this case, framed around the solution they were seeking here. But it also contained a strong statement — for the first time — that a majority of the court questions the constitutionality of how civil forfeiture has evolved and is implemented often today.

All nine justices agreed in Culley v. Marshall that, at the minimum, a “timely forfeiture hearing” is required when the government takes a person’s property through civil asset forfeiture. Civil forfeiture is subject to due process protections, in other words, a point on which the court is unanimous.

How much process is due and what that looks like, however, remains up for debate — and future litigation.

For now, the six conservative justices, in an opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, held on Thursday that the protection Halima Culley and Lena Sutton sought in Alabama — for a preliminary hearing, or retention hearing, to determine whether they should be able to get their seized cars back more quickly than a forfeiture hearing would allow — was not required under the Due Process Clause. The liberals’ dissent, by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, repeatedly criticized the majority for going significantly further than the question presented by the case — over which test should govern such claims — required.

At the same time, however, five justices — the liberals and Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch — made abundantly clear that they welcome further challenges to the “abuses” of civil asset forfeiture as it exists now. A majority of the court explicitly discussed “future cases” and “other due process challenges” that could be brought to address concerns about those abuses.

Until those cases are taken, heard, and decided, however, the votes of Thomas and Gorsuch — in the majority in both of those groupings — allowed a decision on Thursday that will further free, not constrain, government entities to employ the precise abusive practices that they criticized.

Under Alabama’s “innocent owner” defense, both Culley and Sutton had a claim to get back their cars that had been seized when others — using the car without them present — allegedly had drugs in the cars. Culley and Sutton argued that waiting for the full resolution of the forfeiture proceeding before they could get back their cars violated due process guarantees.

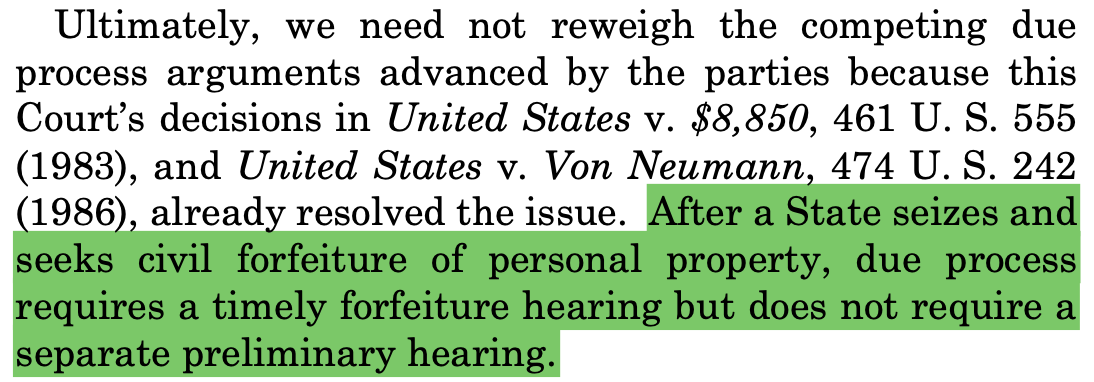

Kavanaugh told Culley and Sutton that, on that front, they were out of luck. Relying on a pair of customs cases, Kavanaugh — joined by all of the Republican appointees — told the women that the earlier cases had already “resolved the issue.”

The forfeiture hearing must be “timely,” but, based on those customs cases, they don’t get any earlier hearing.

In dissent, Sotomayor, joined by the other two Democratic appointees, countered, in essence, that the majority was being short-sighted, if not disingenuous.

And yet.

Gorsuch, concurring with Kavanaugh’s opinion for the court, went off in a different direction than his fellow Trump appointee. He was joined in doing so by Thomas, who previously has raised questions about modern civil forfeiture practices.

Gorsuch opened his concurrence by detailing briefly three points where he agreed with in the majority’s opinion. Then, a shift: “But if all that leads me to join today’s decision, I also agree with the dissent that this case leaves many larger questions unresolved about whether, and to what extent, contemporary civil forfeiture practices can be squared with the Constitution’s promise of due process.”

The entirety of his concurring opinion — despite the fact that his vote, again, makes civil asset more easily effectuated — is dedicated to “highlight[ing] some of” those unresolved questions.

After detailing the relatively new pedigree of modern civil asset forfeiture — ballooning with “sweeping new civil forfeiture statutes” implemented “[a]s part of the War on Drugs” — Gorsuch wrote:

“To my mind, the due process questions surrounding these relatively new civil forfeiture practices are many,” Gorsuch stated unequivocally, going on to describe many ways in which the modern practices differ from historic forfeiture practices.

“Why does a Nation so jealous of its liberties tolerate expansive new civil forfeiture practices that have ‘led to egregious and well-chronicled abuses’?” Gorsuch wrote, quoting a prior Thomas opinion.

Then, he brought it to a close, on behalf of himself and Thomas, explicitly asking for more civil asset forfeiture cases:

Sotomayor, on behalf of herself and Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, did something similar near the end of her dissent — going so far as to provide specific examples of challenges that could be brought.

For Thursday, though, it was a loss for Culley and Sutton — but a decision that put those jurisdictions employing aggressive civil asset forfeiture programs on notice that there is the strong possibility that future challenges with a different framing could meet with success.

Notably, for those interested in how arguments inform understanding of cases, this was a case that — despite its splintered ruling and conflated logic — turned out almost precisely how it appeared to me at arguments in the fall.

![The majority says that “[t]his Court’s decisions in $8,850 and Von Neumann resolve this case.” Ante, at 8. These cases, however, have little to say about what due process requires when an innocent owner seeks to retain her car pending an ultimate forfeiture determination in schemes like those described above. Instead, the claimants in these cases argued that the United States Customs Service took too long to resolve forfeiture proceedings against property seized at the border as part of the claimants’ own alleged violations of customs law. The majority says that “[t]his Court’s decisions in $8,850 and Von Neumann resolve this case.” Ante, at 8. These cases, however, have little to say about what due process requires when an innocent owner seeks to retain her car pending an ultimate forfeiture determination in schemes like those described above. Instead, the claimants in these cases argued that the United States Customs Service took too long to resolve forfeiture proceedings against property seized at the border as part of the claimants’ own alleged violations of customs law.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MfMa!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8b6df6af-d3d8-4dae-a9a9-80c3f260e1c8_1118x492.png)

![In asking the questions I do today, I do not profess a com- prehensive list, let alone any firm answers. Nor does the way the parties have chosen to litigate this case give cause to supply them. But in future cases, with the benefit of full briefing, I hope we might begin the task of assessing how well the profound changes in civil forfeiture practices we have witnessed in recent decades comport with the Consti- tution’s enduring guarantee that “[n]o person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” In asking the questions I do today, I do not profess a com- prehensive list, let alone any firm answers. Nor does the way the parties have chosen to litigate this case give cause to supply them. But in future cases, with the benefit of full briefing, I hope we might begin the task of assessing how well the profound changes in civil forfeiture practices we have witnessed in recent decades comport with the Consti- tution’s enduring guarantee that “[n]o person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9tAl!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3b745c9-c79a-4cc0-a742-1bfa79c10974_1104x490.png)

I had a cynical chuckle over Kavanaugh's statement that the Court didn't have to address the due process claims because prior cases had “resolved the issue.”

In other words, it was "settled law."