Amici: Advancing inclusion in a time when the Supreme Court majority doesn't seem to care

"I think that it is a hard time to look for justice from the Supreme Court." A Law Dork Q&A with the National Women's Law Center legal director, Sunu Chandy.

In the aftermath of the Oct. 31 oral arguments in the two big cases over race-conscious college admissions policies — Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina and Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College — I got on the phone with Sunu Chandy, the legal director of the National Women’s Law Center.

Chandy was one of the key lawyers behind the NWLC-led amici brief submitted on behalf of 38 “organizations committed to race and gender equality” in support of the universities’ admissions policies.

In our discussion, we talked about a wide range of issues that centered on the brief and arguments, but also the question I’ve been asking: What happens if the Supreme Court says these policies are gone, as it appears likely to do?

“For me, this is all about changing our society. For the good,” she told me. “That’s the project. The project isn’t winning a court case, the project is changing our society for the good.”

And this is a project Chandy has been engaged with for a long time, having spent 15 years as an attorney at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and time in the Civil Rights Division at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, among other jobs, before taking on her role at NWLC.

This project — of changing society — she said, will continue regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision in these cases.

“We need to keep fighting this fight,” she said. “Diversity and inclusion doesn’t die or fall with this one case.”

LAW DORK: So, to start off, can you talk a little bit about what it was that was the purpose behind the National Women’s Law Center and other organizations’ brief.

SUNU CHANDY: The National Women’s Law Center is one of the civil rights organizations, and our focus is gender justice, which necessarily includes racial justice — we are advocating for women of color, poor people of color, a range of folks who face sex discrimination and race discrimination. And so, in taking part in this affirmative action brief, our point is to highlight how women of color and our lives will be impacted — in a range of ways — if this very important policy of allowing race to be one factor in the admissions process went away.

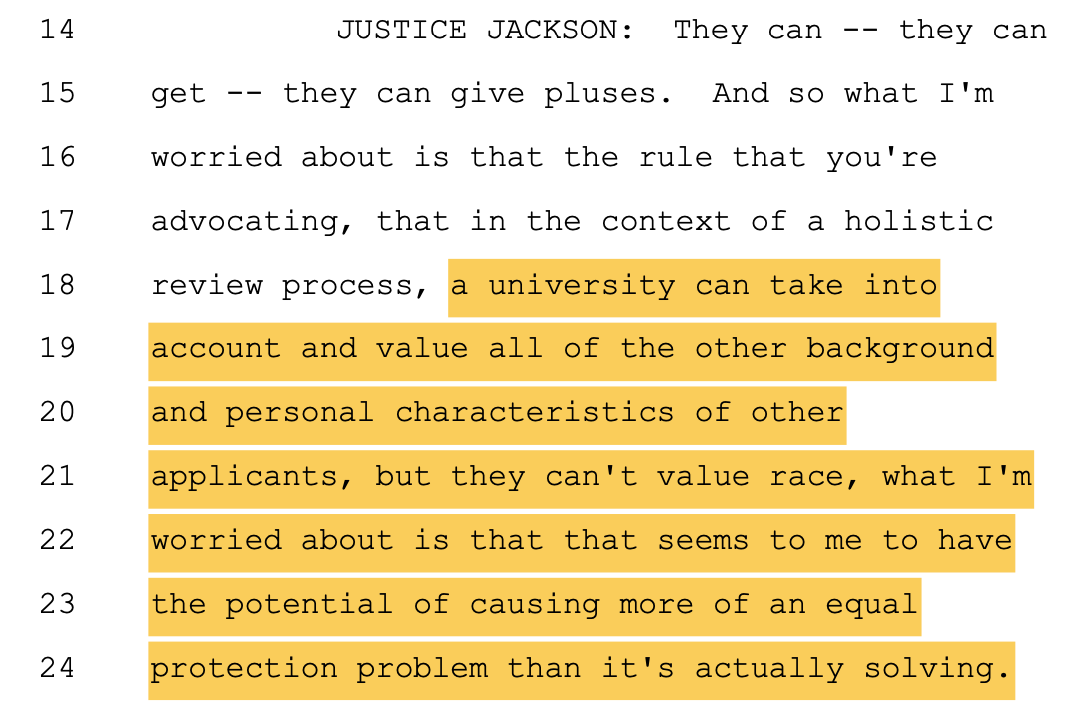

And part of that is this piece Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson raised so clearly in her questions about what happens if you don’t have this policy. Likely discrimination is going to continue — even though that’s not the foundation for this body of case law and precedent, and the focus is very much on the benefits to the entire student body of diversity. What I think was also being named is, “This is necessary because of discrimination.” And I'm glad that she named that, because I think so many people shy away from that, because that isn't the heart of the precedent and the analysis here.

LAW DORK: Justice Jackson really did delve into this idea of the fact that it’s one thing to say that we don’t want to have race specific race-conscious admissions, but that by eliminating that, and nothing else, from consideration, you can be creating, by inverse, sort of almost a requirement of discrimination.

CHANDY: Right. Because you’re going to talk in your essay about every other part of yourself. And I think, in the arguments, I think attorneys [for Students for Fair Admissions] really struggle to say, “No, no, you can talk about in your essay, but they just can’t consider it at all.” That is not reality. So if you’re going to have a rule that says, “It cannot be part of the picture at all,” then you actually can’t talk about it in your essay. And so then you can’t talk about your overall experience, if your race or background is part of that. That is a problem. In our brief, we talk about women of color, and how race and sex, racism and sexism, combine and impact Black women and Latino women and Asian American women in so many different ways in the workplace and in schools. And without having these communities of support within these contexts, it’s incredibly isolating.

When I listened to that argument, I thought about what Justice Jackson talked about in her hearings, how she … was really down one day [at Harvard] and this woman was walking by and she just nodded at her like, “You can do it, you can keep going.” That’s what’s at stake here: Whether you’re going to be there alone. Because you’ve seen in in different places where they’ve changed these rules how the numbers do change. And there aren’t alternatives that really get you similar kind of numbers, in terms of getting the student body that you want.

LAW DORK: Specifically within your brief, I thought that this idea of overlapping identities — and you had the visual representation of that on the court with Justice Jackson and Justice Sotomayor — and how race-conscious admissions helps create not just those singular identity markers, but something more than that. In situations where you are thinking about overlapping identity, the “critical mass” idea becomes all the more important, because you could have a few Black people in a class and yet there still might only be one Black woman.

CHANDY: And then just allowing for differing opinions within people of certain racial backgrounds is so important. Just having one of each category is not going to get us to this pluralistic, multiracial society that we need. And you have all of these corporations lining up to say, “This is so important for our workplace, this is incredibly important for our bottom line, our dollars, our businesses, to have people who know how to get along with different people, and have ideas from different backgrounds, and are used to that when they come into our workplaces.”

And also, as an Asian American myself, there are so many differences within the Asian American community, and there are so many powerful voices saying, “We’re not going to be the wedge. This group cannot be used as the one that’s trying to tear this down.” It’s just simply not the case. This is a political fight. And it is not one that really is going to benefit Asian Americans. And so, we also specifically in our brief talk about Asian American women, and the discrimination that’s based on race and sex grounds, and why having more inclusive admissions policy that allows race-conscious policies to look at the whole candidate is really important.

LAW DORK: You talk a lot in the brief about how a key part of the value of this is the ways in which creating a diverse student body fight stereotypes. And, again, the impact of decreased diversity on being able to fight stereotypes specifically when dealing with overlapping areas of diversity.

CHANDY: We do break that down — in terms of different groups of women of color, who face different kinds of stereotypes, negative stereotypes: whether it’s that you’re not going to be able to perform well, or whether you’re going to be quiet, or you’re going to be exotic, or you’re going to be a “model minority,” all of these damaging stereotypes. And the more you can actually have students interacting with each other, as full human beings, the less people are going to be walking around in our society with these myths that are, frankly, harmful.

LAW DORK: Now, we can talk about all those changes that are needed and goals that are advanced by race-conscious admissions. But you listened to the oral arguments in the two cases as closely as I did. And, it didn’t go well for your side of the briefing.

CHANDY: Even under their model [of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s statement in 2003’s Grutter v. Bollinger that affirmative action policies would, she expected, not be needed in 25 years], we’re not even there yet. And we know we’re not there, period. But, why is this being taken up now — but for the political moment of one side thinking they could potentially win. Just as with Dobbs [v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization], with Janus [v. AFSCME], and all of these cases where precedent has been overturned and where things actually have not changed, it really gives us pause when we think about the integrity of the Supreme Court. And, as a legal director, it gives me a lot of heartburn, as I’m sure it does many others, to think about [the fact that] we are pleading to a system, which their own justices on the court have said, directly and indirectly, in so many ways: What is this court looking to as a guiding principle?

LAW DORK: As a legal director then, how do you — you have this compelling brief that lays out a case, but you’re still bringing it up against a court that likely has a majority of justices who aren’t really going to consider precedent compelling. What do you do?

CHANDY: I think that it is a hard time to look for justice from the Supreme Court. And it’s also a time where we don’t want to just leave it to our opponents. We named who is going to be harmed if this changes, we named the groups that are being used as a wedge — to say, “Not in my name.”

And we are often cited by the dissents. We are giving support, if nothing else, to a dissent to say, “We know what is true, we know what is right.” And those many, many schools and organizations, corporations, nonprofits, advocates, multiracial organizations — we are [all saying], “We believe that people should have this opportunity.”

I can only hope that, at the very least, that the court understands we’re not there yet. We haven’t reached a day of racial equality. … We have much work to do. We’re just on the road, and to say that we’re there, and we’ve reached this place of equality where people’s backgrounds aren’t going to be considered is just a myth.

LAW DORK: If they do issue a decision to say that race-conscious admissions are unconstitutional, where do you go from there?

CHANDY: I think some of those questions that were teed up during the argument, they become a lot less theoretical, because how is that going to work on the ground? I think there’s a lot of unknowns about how this will play out. But I think there’s a lot of different ways to get a bad opinion. There’s a range. There could also be an “It’s not time yet” [decision]. I don’t know that that’s going to happen. That’s only a few years [until O’Connor’s 25-year benchmark], but it does sort of give us some more space.

LAW DORK: Is there anything else that you think that that people should be thinking about in this interim between the arguments and the decision?

CHANDY: As I was getting at before, many companies, corporations, schools have done so much — often led by students, by workers, by impacted communities — to do proactive work for the good in terms of racial justice, and gender justice, and LGBTQ inclusion. And what we are talking about — with the laws and cases and these rules — are but one tool in our toolbox. But so many organizations are doing good work. And they’re doing good work, whether or not it’s legally required.

For me, this is all about changing our society. For the good. That’s the project. The project isn’t winning a court case, the project is changing our society for the good. And rules, regulations, court cases are one avenue. People banding together and pushing — you know, we now have a union at the National Women’s Law Center, which is wonderful. Many nonprofits are going in that direction. These are all places where you can have diversity, inclusion, EEO pieces as well. And our federal government can have executive orders that tell federal agencies what to do for the good, to include LGBTQ workers, to implement Bostock, to push for diversity and inclusion in many, many different ways.

Diversity and inclusion doesn’t die or fall with this one case. We, of course, want to have fair admissions policies that allow students to talk about their background, including their race, and having that be part of the admissions process. We think that’s right, that’s important, that’s necessary. But, no matter what happens with that, we will find ways to push for what we need, which is an inclusive and fair society.

Hi, Chris - Just a quick note to say that I'm really appreciating the content. A couple of pieces have been useful for work, and I hope that continues.

This was great, and very clarifying about the issues at stake.